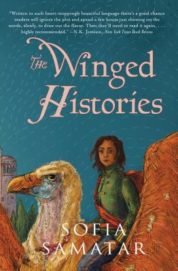

Sofia Samatar

Sofia Samatar

Small Beer Press ($24)

by Jane Franklin

Sofia Samatar’s second novel is an imagist epic fantasy, a feminist and anti-colonialist reworking of one of those spongy-thick novels with maps at the front (it has a map at the front) and, like her first novel A Stranger in Olondria, a book about books, reading, and language. It is dazzlingly beautiful and as close to perfect as a reader can hope.

In its four sections, separated by material entitled “From Our Common History”—perhaps a book, perhaps our actual common history given voice—four women experience a civil war: Tav, the duke’s daughter, who cons and charms her way into military training; Tialon, the daughter of the fundamentalist Priest of the Stone; Seren, a singer of the desert nomads; and Siski, the daughter of a noble house, brought up to be a pawn in a marriage intrigue. All the appurtenances of romance are here—the military training, the hopeless battles, the loyal retainer, the beautiful horses ridden superbly by nomads with flowing hair, the glittering parties and flashing swords—but this is also a story about the contradictions and limits in women’s use of language when language is formed by and purposed for patriarchy.

The imprisoned Tialon, for instance, writes the story of her dead father because her father’s story is what she tells herself is the important one, with her own experiences first creeping into and at last taking over the narrative. Seren sings the traditional songs of dead heroes and speaks the che, the women’s language with its artificially limited vocabulary— “[the] che inside me like a well of gold,” she says of her childhood. “And then I grew up and this gold was worth nothing, nothing. You can’t use it anywhere. It’s only for fighting with other women, or for crying.” And there are letters lost, forged, never sent, stolen and destroyed—women’s writing that doesn’t make it into history.

Didactic or critical fantasy often gives the reader questions to ask. “Look at the world and find out where the power really lies, or where the women are; ask who built the castle and whether they were free laborers or slaves, pay attention to who dies in the great battles.” It tells us what to look for. The Winged Histories is about what we can’t see because it has slid away, escaped, been hidden or lost. We as readers can see what is in the lost letters or Tialon’s sketches of herself traveling a world she’s read about but never seen; we observe Siski’s life as a refugee, when she calls herself Dai Fanlei, Miss Apple, and turns mattresses for a pittance. But these are the things that don’t make history—the paper ephemera, the experiences lived but never written down or spoken. It’s a kind of trick; we can see them in this book, which tells us that we can’t see them here, in our world.

Samatar’s prose, always wonderful, has really grown into itself. She has a fine mastery of tone—the passages from Our Common History, for instance, are ironic and sly, as when describing Prince Andasya: “‘His charm perfumes the air for a hundred miles,’ gushes a writer for The Watcher. Hearts flutter when he enters the army: if he should be injured or killed! But then—how heroic of him to enlist! When he puts on his scarlet guardsman’s jacket, his lips look redder than ever.” Even Samatar’s semi-colons are satiric, and her use of the present tense in these sections recalls Angela Carter.

The novel’s anti-colonial politics are visible throughout, but come to the fore in the elliptical chapter narrated by a grieving Seren, “The History of Music.” Here Samatar uses repeated images, phrasing and pacing to create a feeling of incredible tension. Seren is speaking to her lover Tav, who has returned from her failed uprising, the uprising which has not delivered an autonomous Kestenya but has instead killed many of Seren’s people:

But let’s say it, let’s say what there is to say. Let’s get it out, let’s write, let’s put it there: You are from everywhere and I am from Kestenya. You are from mansions and palaces and cities and mountains and emptiness and pleasure and I am from the great plateau . . . . Your grandfather prayed with the great Olondrian visionary who made your grandfather sleep on planks that brought out sores on his soft and timid body, and my grandfather slept in a mass grave on the road to Viraloi where he was hung by the heels with seventeen others until they died of thirst.

There’s tremendously more to this book—the strange sense of leisure imparted by how it lingers over snapshot-bright instants while eliding battles, councils, and meetings of the great, all of which take place in an allusive sentence or offstage; the imagistic landscape writing; the rare combination of a fantasy plot with a modernist psychological approach; the constant theme of misperception and hiddenness. And that is to leave out the “Drevedi,” the demons of myth who ruled—or so it is said—an Olondria before Olondria, and who exist as the real of the outside and the other, the strange and marvelous which can be sympathized with and loved (or cruelly killed, drowned in hot wax) but never explained into sameness. With its deft exploration of the tension inherent to inhabiting a marginalized subject position, The Winged Histories is one of the finest fantasy novels of 2016, or any year.