James Robertson

James Robertson

Other Press ($15.95)

by Catherine Rockwood

James Robertson is a Scottish author specializing in carefully researched, big-concept novels that address what’s known, mostly within the UK, as the Question of Scotland. That being: what is to be done about a “country that is not fully a country, a nation that does not quite believe itself to be a nation”? His readership has been largely British until now, but the world is coming to him and his set of concerns this year, because the issue that provokes and confounds Robertson as an author—what is to be done about Scotland?—has captured global interest due to the recent referendum on his nation’s independence.

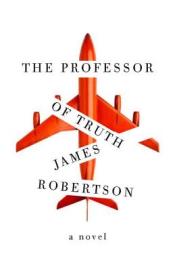

Unfortunately, Robertson’s latest and fifth novel The Professor of Truth, which seems pitched to a crossover market, is a dicey place for international readers to start their travels with this writer. If you’d like to do some advance thinking-via-fiction about how the referendum might go and what it might mean, pick up an early James Robertson novel like The Fanatic (2001) or Joseph Knight (2003). You’ll have to read some Scots, but you can do it: just dive in, and keep the free online Dictionary of the Scots Language at hand (www.dsl.ac.uk). The books are worth the effort, works of historical fiction that are deeply invested in making past events felt in the present tense, a thing which Robertson pulls off with subtlety.

Despite its failings, The Professor of Truth deserves some focused attention due to an entirely different strain of recent geopolitics. The book is a fictionalized, revisionist account of the aftermath of the 1988 Lockerbie bombing, which rained its awful freight directly into a small town in the Scottish Borders. Comparisons with the recent downing of MH-17 are inevitable, and the novel therefore stands as a sort of test case for writing about the moral, legal, and emotional consequences of the violent destruction of civilian aircraft.

In a nutshell: hard to do well. Robertson’s novel is hugely influenced by the real-life truth-finding campaign conducted by the English doctor Jim Swire, who lost his 23-year-old daughter Flora in the 1988 downing of Pan Am Flight 103. Swire has for many years been a vocal dissenter from the official legal verdict in the Lockerbie bombing, which rests, at present, with one party held guilty: the now-deceased Libyan citizen Abdelbaset Al-Megrahi. The Professor of Truth’s main character, Alan Tealing, is certainly based on Swire himself, though distancing efforts have been made. Tealing, for instance, is an English professor and not a doctor of medicine like Swire; Tealing loses his wife and young daughter in the plane crash, not a beloved adult child. But these are too-thin covers for a too-narrow authorial purpose.

Over the course of the novel, Tealing goes haring off to Australia in search of new evidence that could initiate a retrial for “Khalil Khazar,” a fictional version of Al-Megrahi. He is provoked to do so by a visit from Ted Nilsen, a terminally ill American intelligence agent who confirms Tealing’s suspicion that dubious international politicking led to the selection of Khazar as a scapegoat, and that the real bombers have not been caught. This set of characters, ideas, and events constitutes an attempt at translating the terms of Jim Swire’s Lockerbie truth-finding campaign into a fictional setting.

Robertson tries very hard to work all the levers that might lead us to accept his polemical plotline as an un-dogmatic work of imagination. The book’s presentation of Tealing as an isolated crusader for justice, operating in an environment of international espionage, conspiracy and paranoia, provides links with a range of famous texts and authors, and makes a case for Robertson’s novel as the hybrid descendent of works like Shakespeare’s Hamlet, Dumas’s Count of Monte Cristo, Conrad’s Secret Agent, and the Scottish spy-fiction of John Buchan. All of the above are name-checked or alluded to in the course of the book. But the focused activism of the work baffles its wider novelistic ambition. Robertson manages throughout to keep track of all content relating to the confusions and permutations of the legal case against Khalil Khazar, but his control of the novel’s literary referents and sources is erratic in the extreme.

Taking one example among many: when Tealing, in Australia, questions his own motivations for chasing down the witness whose testimony sent Khalil Khazar to prison, and begins to wonder why he’s still grinding along at the Case and whether it’s worth going on at all, we get this:

. . . What is it, to face death? What does it mean? Is it a braver thing to do than to face life? Is there even a difference? If you are not afraid, then to be brave is nothing. To be afraid and go forward, to meet life or death shaking but to go anyway . . . that surely is the mark of bravery. To be a coward and yet still to act, that is the thing.

It’s Hamlet, or bits of Hamlet: a flattened prose version of “To be or not to be.” There’s nothing inherently wrong with Robertson making the reference because Tealing, like Hamlet, is an isolated, possibly deranged lone wolf pursuing impossible justice. The parallel is plausible. What’s wrong is Robertson’s apparent amnesia about the fact that Tealing is supposed to be an English professor, someone who would almost certainly display awareness about the Shakespearean source of his thoughts. The fact that he doesn’t causes the book to flounder.

Robertson ‘s version of Hamlet negates Tealing’s internal consistency and erases most of the original Shakespearean phrasings, retaining only an altered husk of their content. The result is something very close to plagiarism, a marker of self-doubt. In the case of The Professor of Truth, Robertson was right to doubt. The book is flawed; it is also, though the world has cause to wish otherwise, timely.