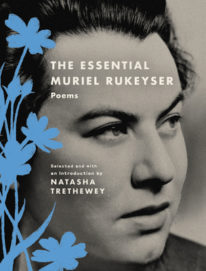

Muriel Rukeyeser

Selected by Natasha Trethewey

Ecco ($16.99)

By Warren Woessner

In selecting 75 poems from Muriel Rukeyser’s prodigious body of work, former U.S. Poet Laureate Natasha Trethewey took on a daunting task. Rukeyser was born in 1913 and died in 1980, one year after her collected poems was published. She was an active journalist for left wing organizations and throughout her life she was artistically (if not personally) witness to five wars and decades of feminist, environmental, and racial progress and injustice.

In selecting 75 poems from Muriel Rukeyser’s prodigious body of work, former U.S. Poet Laureate Natasha Trethewey took on a daunting task. Rukeyser was born in 1913 and died in 1980, one year after her collected poems was published. She was an active journalist for left wing organizations and throughout her life she was artistically (if not personally) witness to five wars and decades of feminist, environmental, and racial progress and injustice.

Trethewey anchors her selections for this new and timely volume with Rukeyser’s longer poems. “The Book Of The Dead,” about the Hawk’s Nest Tunnel Disaster, may be the best known of these and occupies 45 pages. This poem tells the story of an attempt to widen a hydroelectric tunnel after pure silica had been discovered, the exposure to which led to the rapid deaths of hundreds of workers, many of whom were Black or recent immigrants. Many were buried in mass graves. The sections are each individual poems that record “Statements” by the miners and their family members, as well as Congressional testimony. They read like found poems:

George Robinson : I knew a man

who died at four in the morning in the camp.

At seven his wife took clothes to dress her dead

husband, and at the undertaker’s

they told her the husband was already buried.

The poem does not mention the Tunnel Disaster directly, but is more of a call to continue to battle the forces of injustice everywhere: “What three things can never be done? / Forget. Keep silent. Stand alone.” Another long poem, “Letter to the Front,” pertains to the Spanish Civil War, which began while Rukeyser was in Barcelona, but contains stanzas that could have been written today:

But our freedom lives

To fight the war the world must win.

The fevers of confusion’s touch

Leap to confusion in the land.

We shall grow and fight again.

The sickness of our divided state

Calls to the anger and the great

Imaginative gifts of man.

Rukeyser can walk that talk. She was arrested early in her journalistic career while covering the trial of the Scottsboro Boys and again later during a protest against the Vietnam War. The poem “The Gates” describes incidents in the 1970’s when she traveled to South Korea to plead for the release of the poet Kim Che Ha, who had been sentenced to death for criticizing the current regime. The collection includes further poems about her anti-war activities, as well as about her sexuality.

The one drawback of this new volume is that Trethewey’s introduction is too short. A reader new to Rukeyser’s work would certainly want to know more about her life, especially since she did not tread the well-worn path of academic advancement. The central message of her work, however, is summed up in her short poem “In Our Time”:

In our period, they say there is free speech.

They say there is no penalty for poets,

There is no penalty for writing poems.

They say this. This is the penalty.

In under 200 pages, The Essential Muriel Rukeyser lives up to its name, presenting the positive force of her mission concisely. In this it mirrors much of the poet’s own brilliant work, as captured in the opening lines of “Wherever”: “Wherever / we walk / we will make // Wherever we protest / we will go planting.”