Geoffrey Hill

Geoffrey Hill

edited by Kenneth Haynes

Oxford University Press ($27.95)

by Patrick James Dunagan

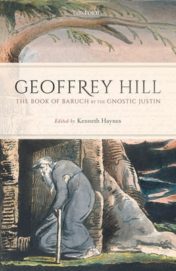

An engaging curiosity, The Book of Baruch by the Gnostic Justin was meant to be Geoffrey Hill’s final book of poems, and at the time of his death in 2016 it was left unfinished as he intended. Editor Kenneth Hayes tells how Hill planned “a posthumous work, to consist of as many poems as he would live to complete.” With its extravagant title, a somewhat obvious foil of biblical-sounding esotericism that makes the cover art by William Blake a perfect fit, it’s a robust burst of late work capping off an already extraordinary late-in-life run: Of the near thousand pages of Hill’s Broken Hierarchies: Poems 1952–2012, only roughly 150 pages contain poems written before the 1990s. While Hill is broadly recognized as a great formalist, The Book of Baruch presents 271 short sections composed of densely compact long lines of free verse. Arguably resembling a prose poem, these not-quite-paragraphs deliver a thunderous, line-by-line, biblical cadence while internal and off-rhymes proliferate at a near (but not quite—Hill does not abide lightweight mess) sing-song rate.

The writing is self-reflective, as if casually caught up with its own concerns. Hill often comments upon how it’s going: “This, it is becoming clear, is more a daybook than ever The Daybooks were.” The Daybooks were a multi-volume set of poems by Hill, written chronologically yet not with the same loose tone and style as found here; Hill might even be said to be relaxing with The Book of Baruch, as his statements are often simply put and to the point: “Je est un autre: the little rotter was quite right, of course.” Such moments make for fun reading, but shouldn’t be taken as the main thrust of the book. Hill’s poetry remains archly literary (you must be able to recognize “the little rotter” as Rimbaud, for example) and heavily indulgent with exalted vocabulary that zips right along. Images are unfurled at an astounding pace as Hill’s thoughts link up his personal experience with historical events and highbrow balderdash. For instance, there’s a lengthy run of pages where he riffs on various manifestations of the “Poem as,” a series of sui generis statements regarding his own alchemical poetics:

Poem as scimitar-curve, shear along sheer, a ‘Tribal’ class destroyer, veteran of

the North Cape run, bearing down on a submarine that has struck and

already gone from the scene, leaving sea-rubble wretchedly a-swim,

thickslicked in oil.Rapid hapless signal flags, the merchantmen's red rags, warp and snatch on the

Arctic wind. Frantic asdic, its wiped mind becoming, with old memory

and new writing, something forlornly grand.Poem as wall map or table chart of a desperate, remote, protracted bid to

escape. Poem in due time a diminished aide-mémoire to vanished

strategic priorities of fire.Poem as equity release—whatever that is.

Poem as no less an authority on history than whom?

As always, it helps to look up words not recognized in order to get the full effect of Hill’s work. For example, “asdic” refers to an early form of sonar used to detect submarines. Figuring that out and re-reading the lines brings the full force with which Hill’s referencing of his post-World-War-II-era adolescence are echoing through to a finer point of apprehension. While the repetitive listing technique used here brings to mind Clark Coolidge’s recent book Poet, containing his jazz-fueled rhythmic blast on “the poet” as manifested across his lifetime, the books are otherwise dissimilar, though both deal with perennial questions plaguing those who spend their lives engaged in poetic activity.

Among the most illuminating passages in The Book of Baruch by the Gnostic Justin are those where Hill drills down on readings that have mattered to him, sharing his passions even as he admits the insubstantial nature of the material at the heart of his confession: “in re-reading Desnos on the alchemical, I sense something slender but continuous and intense that I can render of use to my own verse: this I am eager to confess, though the issue, the residue, is so meagre.” Despite Hill’s concern, this is not at all a paltry divulgence. At times the most rewarding of artistic fare is generated from the barest of threads, minute connections triggering the imagination. It’s worthwhile to go read “Desnos on the alchemical” ourselves to see if we might find any bit of the same “residue,” no matter how “meagre” it may turn out to be. That is, of course, if we’re able to ascertain what passages by Desnos Hill had in mind. (There’s a good chance it may be his article “Le Mystère d’Abraham Juif,” published in the journal Documents in 1929, which discusses walking tours the Surrealists undertook to historical alchemical sites around Paris).

Again and again, lines that offer flashes of Hill’s ars poetica remain the most compelling to return to: “Words attract words as trouble attracts trouble and yet, to succeed, we must ditch all safeguards; and see and think and speak double.” The lessons for writing accrue, as does Hill’s emphatic insistence upon his most cherished views: “The great, let me repeat, are the dead of whom I approve, whom indeed I love.” His passions become our own. The expanse of his grasp engages the imagination, inspiring further explorations into the meaty haunts generously presented in this last work.