Thi Bui

Thi Bui

Harry N. Abrams ($24.95)

by Jeff Alford

The best memoirists reveal familiarity in the foreign. Challenged with the task of presenting their lives as something another person would read, they must find a way to break apart the uniqueness of their history into something more broadly connective, pushing readers towards an abstract sort of reflection and empathy. A story of a mother and a daughter, for instance, should transcend the specificity of motherhood and daughterhood and present to all readers something with which they can connect. In the memoirist’s ether, the personal needs to transfer from writer to reader.

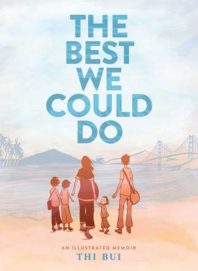

Thi Bui’s comics memoir The Best We Can Do is about her family’s emigration from Vietnam in the ’70s and their naturalization into the United States. A tremendous achievement, the book brilliantly renders its feelings of alienation with inclusivity and empathy, focusing simultaneously on one specific family and corresponding universal themes of love, kinship, and growing up. Bui’s art is immediately accessible, cartoonishly sweet but disarmingly weighty.

When the story opens, Bui is about to give birth. She's shaken with both physical and emotional uncertainty but can recognize that this experience will, for once, definitively give her something she has in common with her mother. “Family is now something I have created—and not just something I was born into,” she writes. Upon the birth of her child, she, like her mother, will have shifted from individual to caregiver, and they will share a parallel responsibility to do the best they can for the life they made.

But did her parents do the best they could? This is a painful question to ask, as Bui’s relationship with them was one more of efficiency than joy. Growing up, they were hardworking and critical, tired and often irritable. Although now divorced, her parents see each other often, seemingly too indifferent to care about moving on. As a new mother, Bui vows to be for her child what her mother wasn't. “Proximity and closeness are not the same,” she astutely notes.

The memoir unfolds backwards into the story of her parents, known simply as Ma and Bo (although careful readers can discover their real names with a little digging). Bui, as an adult, can be seen throughout the book as a considerate listener with a newfound courage, finally asking her parents the questions they never spoke of growing up. “Me and Bố,” she writes, “we’re okay now. To stop being scared of him, I grew up and went away. And now that I’ve come back, we can sit in my mother’s studio, both of us visitors, neither one owing the other.”Alternatively, she confesses “writing about my mother is harder for me—maybe because my image of her is too tied up with my opinion of myself.” Details emerge and color vaguely-remembered outlines about their family of six: stories of miscarriages, illnesses, political pressure, and suicide attempts reframe her parents’ tribulations with all the subtle difficulties that Bui could never have noticed as a child in Vietnam.

Brutal chapters are devoted to her family’s escape from Vietnam by boat, sharing the hull in starving silence with other refugees. Bui provides readers with an important reminder that the war in Vietnam was so much more than a Walter Cronkite narrative or an Eddie Adams photograph: “I think a lot of Americans forget that for the Vietnamese, the war continued, whether America was involved or not.” They land in a camp in Terengganu, Malaysia, and from there journey, briefly, to distant family in Indiana before settling in California.

There, they tried their best. With no outside pressure, the family was left to nurture and cultivate new identities as American immigrants:

Little by little, our parents built their bubble around us—our home in America. They taught us to be respectful, to take care of one another, and to do well in school. Those were the intended lessons. The unintentional ones came from their unexorcised demons . . . and from the habits they formed over so many years of trying to survive.

Now, as a new mother, Bui can see those unexorcised demons for what they truly were: a struggle between identity and selflessness, adrift in homeless disconnection.

In her preface, Bui explains that she was drawn to the graphic novel in an effort to solve “the storytelling problem of how to present history in a way that is human and relatable and not oversimplified.” She writes that she had to learn how to “do comics” in order to tell her story the way she wanted. The results are remarkably polished. Bui approaches her portraiture with a kind of facial minimalism, finding perfectly emotive subtlety in the slightest of marks, like an upturned smile or a slightly furrowed brow. She masterfully synchronizes the themes of her memoir with the style in which it is drawn: she finds the best she can do, embracing its limitations while exemplifying its care.