by Marina Chen

by Marina Chen

Founded in 1966 by Robert Hershon, Emmett Jarrett, Dick Lourie, and Ron Schreiber, Hanging Loose Press has put hundreds of books and magazines into the world, much of it focused on emerging writers—including high school writers, regularly included in Hanging Loose magazine. The independent press that first published Sherman Alexie, Cathy Park Hong, Maggie Nelson, and many others, proves year after year that young writers are as important to them as their roster of professionals, even after six decades of publishing.

In the following interview, former HL intern and high school writer Marina Chen talks with the current co-editors Mark Pawlak, Dick Lourie, and Caroline Hagood about Hanging Loose history, philosophy, advice, and thoughts on literature and the writing youth of today.

Marina Chen: Hanging Loose has been publishing high school writing since the very first issue of the magazine in 1966, and for decades was the only magazine in the business doing that. Back then, what motivated the editors to include high school writing?

Mark Pawlak: I had just graduated high school when the first issue of Hanging Loose appeared, so we’ll need to hear from Dick on that count. But I will say that when I joined HL as an editor in 1980, one of the things that attracted me was its commitment to publishing teen writers.

Dick Lourie: Just before our first issue my cousin Martha, then thirteen, showed me two poems by a friend of hers, Deborah Deichler. “Knockout,” Bob and Ron and Emmett and I all agreed, so we thought OK, terrific poems, but really, by a high school student? Well, why not? A few issues later, we began the regular section.

MC: You’ve also published four anthologies of that high school writing. How did that come about?

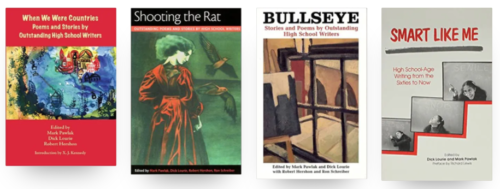

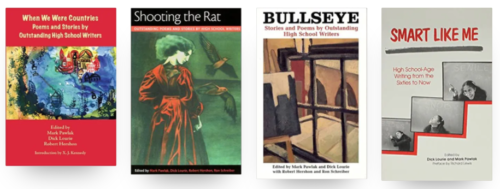

MP: One frequent topic of discussion among the editors was how much readers liked the high school poetry, so we really should collect the best of the work and publish an anthology. But that idea always got tabled; our more immediate concerns were getting out the next issue and the individual authors’ books we had on the schedule. Eventually, I volunteered to take the lead in pulling the material together. Dick offered to help. And so Smart Like Me (1986), which gathered the best poetry from the first twenty years of the HL high school section, came into being.

Naively, we thought this anthology would appeal to a trade publisher; we made inquiries. In those days there were collections of poetry written for teens, but by adults. Although never explicitly stated, it became clear to us from the publishers’ responses that they were afraid such a collection wouldn’t sell well to schools and libraries. The poetry we’d collected was too raw, too honest, too frankly perceptive of the lives of teens, their parents, their teachers—their world. Censorship by local school boards combined with outcries from PTAs was no doubt also on their minds. But it was for just those reasons that we believed in our anthology project, so we went ahead and published it ourselves.

To our delight, it garnered very positive reviews: “The levels of insight and maturity are often astounding.” (School Library Journal). “Any teacher who’s worked with teen-age writers will be cheered and re-inspired.” (X. J. Kennedy). “Give it to old fogies who maunder on about what the younger generation’s coming to.” (Village Voice). And it sold very well.

MC: That response must have persuaded you that you were onto something.

MP: It certainly did. As you know, we’ve gone on to publish three subsequent anthologies, Bullseye (1995), Shooting the Rat (2003), and When We Were Countries (2010). I’m very proud of our role as forerunners in this regard, but it’s important to remember that innovative ideas are frequently of their times, floating in the cultural atmosphere, awaiting someone to pluck and develop them. With respect to poetry by young people, Teachers and Writers Collaborative started the same year as Hanging Loose. T&W hired poets to teach in schools and published curricula for teachers to use in teaching poetry, especially, although not exclusively, contemporary poetry. Many of the poets associated with T&W are friends of and published by HL. And like us they’re still going fifty-plus years later! So, we weren’t alone in valuing poetry written by young adults.

DL: Those early years in New York—Mark is right: it really was a movement, to have poets teach in schools, where they taught students and, in a way, mentored teachers by example. Organizations sprang up focused on poets working in particular states: both New York and New Jersey had “Poets in the Schools” programs, and the organizations were able to get grants from state governments. At various points in HL’s early years, Bob and I and Emmett all did poetry programs in schools. So, our direct contacts formed another conduit for high school writers to the magazine. Such programs still exist and there are still a few poets who can make a living by their work in schools, though funding for the arts has been cut in general.

MC: How have high school writers usually found HL?

MP: I think the answer has changed over time, but mostly it has been teachers who pointed students to HL, as Dick just mentioned. And the landscape has changed for teens who want to share their writing. There are many more outlets to publish their work, including journals specifically devoted to teen writing and summer writing classes and workshops.

DL: And I think the situation now is different from when Caroline was in high school.

Caroline Hagood: Yes, as Mark said, there was no “class assignment.” The idea of sending to HL was suggested to me by my amazing high school poetry teacher, Marty Skoble. I remember being so surprised that any magazine would be willing to consider the work of a high school writer. I think the way the climate has changed today is that now students might also hear about these kinds of opportunities on social media. I saw a Twitter conversation recently where someone was asking where she could send the poetry of her talented high school student, and I was so happy to see someone suggest Hanging Loose.

MC: How can young writers get involved? And for any prospective writers reading this, is there anything specific you are looking for?

MP: Our website has a page with guidelines for high school writer submissions. Our dear deceased Robert Hershon, a founding editor, liked to say, “the past is precedent.” Meaning, read a copy of HL magazine (there are 111 issues to date) or one of our high school anthologies.

DL: Yes, that’s really important. Poetry is like any other profession; you don’t go into it without knowing how it’s done. Poetry isn’t “expressing thoughts”—it uses thoughts and feelings to create art. That’s a skill. If you wanted to be an electrician, you might start as an apprentice. To be a poet, you start developing your skills by reading poetry. That’s the way you get a sense of it. So, I think it’s not necessarily something specific we’re looking for, other than some indication, in a person’s writing, of a familiarity with poetry, with how poets over the years have transformed their thoughts and feelings into poetry—in other words, keep writing and, just as important, keep reading.

CH: I am going to defer to Emily Dickinson on this one, in terms of what I’m looking for, at least: “If I read a book and it makes my whole body so cold no fire can warm me, I know that is poetry. If I feel physically as if the top of my head were taken off, I know that is poetry. These are the only ways I know it. Is there any other way?”

MC: It is an eternal human pursuit to want to know what came before. Especially for writers, knowing this is power and can enhance one’s writing. As a previous high school writer for Hanging Loose, your fourth high school collection When We Were Countries was a chance to meet my predecessors. How does being published in HL usually affect high school writers? What do they go on to do?

MP: As a former HL high school writer, Caroline can best answer how it affected her (Ghosts of America: A Great American Novel, her novel, was just published by HL). And in her essay in When We Were Countries, Joanna Fuhrman, who just published her sixth poetry collection with HL, writes about how it affected her. I keep a list of alumni of the HL high school poetry section who have gone on to writing careers. In just the past year, Donovan Hohn, for one, a New York Times bestselling author, published a new collection of essays, as did Sejal Shah, both to widespread acclaim. But there are many, many more.

But other alumni of the high school section go on to distinguish themselves in a great variety of fields as artists, journalists, economists, editors, scholars. Their subsequent career paths are documented in the contributor notes at the back of each anthology. They make fascinating reading, which brings me back to what the Village Voice said about “old fogies who maunder on about what the younger generation’s coming to.”

DL: And one of our early high school poets, Michael Rezendes, was part of the Boston Globe’s “Spotlight” team that received a Pulitzer Prize for their scathing revelations about clergy child abuse in the Catholic Church. Our very first high school poet, Deborah Deichler, became a painter and a professor at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts.

CH: I can’t answer for all poets who were published by HL in high school, but, for me, it really did contribute to my youthful belief that I could build a career out of poetry. I remember graduating high school thinking the world believed poetry to be as important as HL did and as my high school did, only to be quickly disabused of that belief. But I did go on to make a career out of poetry in a way, by getting my PhD in English at Fordham, and now by working as an Assistant Professor of Literature, Writing and Publishing and Director of Undergraduate Writing at St. Francis College in Brooklyn, as well as my recent role as the Faculty Advisor for Unbound Brooklyn.

MC: The rise of slam poetry and an overall growth of the poetry world available to young writers have caused a rise in readings and oral competitions. How do you think the relationship between written and spoken word poetry has developed and affected high school writers across HL’s decades of interaction with them?

MP: Now it’s my turn to sound like an old fogy. I believe competition in that public sense is anathema to poetry. Friendly rivalry, challenging one another to greater achievements as artists is something different.

As to the questions of “page versus stage,” I think there is a genuine tension there. A poem that is powerfully achieved on the page can also affect listeners just as powerfully hearing it read aloud. However, a good “stage poet” can put over a poem that falls flat on the page. And I recognize that spoken word poetry has expanded interest in poetry to young people who might otherwise have been put off by poetry in books or in the classroom. If enjoying a spoken word reading leads them to a deeper immersion in all kinds of poetry, all the better.

DL: The only thing I would add is that one important aspect of the “page versus stage” tension is the need for mutual respect. The only thing I object to is the occasional characterization of us “page” poets as a bunch of stuffy aristocratic types whose readings reach heights of boredom.

MC: What does HL hope to achieve with these four high school anthologies? Why is it important to share young work, for the poets and the readers, and why should young readers read each other?

MP: The readership of a poetry magazine like Hanging Loose is limited, so by its very nature an anthology is a way to reach a wider audience. Much of what passes as representative of teen life and teen issues in the media and on the Internet is commodified cliché. Real poetry written by one’s peers speaks to teens differently. Our anthologies can and do play a role to enrich teen readers’ lives and their imaginations.

CH: Reading poems from other high schoolers in Shooting the Rat was life-changing for me. These poems made me feel alive, electrified, less alone. I would also add that I don’t think it’s going too far to say that there are kids out there whose lives this kind of exposure could even save.

DL: And as history, reading through all four volumes gives a sense of how young people’s poetry, as a reflection of American poetry in general, underwent changes in style and focus.

MC: Over time, have the identities of HL high school writers changed as well? And how does this reflect upon HL as a traditionally safe space for young writers?

MP: Over more than five decades we have never needed to have a special issue of our magazine dedicated to LGBTQ+ writers because we’ve always been open to their work. Tim Robbins, then a high school student from the Midwest, started sending us poems with explicitly gay content in the early 1980s. I think he holds the record for the most poems by a writer of high school age to appear in Hanging Loose. He must have thought of HL as a safe place, and forty-plus years later he continues to send poems to HL. He recently asked me to write an endorsement for his first full poetry collection.

DL: And our late co-founder, Ron Schreiber was a militant, out, gay activist in the New York of the 1960s. He played a crucial role in mentoring young, gay writers.

MC:, The 2000s generation seemed particularly preoccupied with themes like reconnection of broken families, international diversity, and the immortal quality of first love—but most of all, the uplifting of one’s own voice. I also noticed the first hues of fierce racial-inequality-fueled rage that colors today’s current youth in When We Were Countries. Are these themes similar or different throughout each cycle of HL high school writing? What does this say about what high school writing offers to the literary community?

DL: Thoughtful question indeed. I think the high school poets and fiction writers today do reflect on how they live in the world that we, the elders have made (as each generation does) for them. To read their work is to read how they feel about where they find themselves now. I feel sometimes with a high school poet that I’m learning about someone in the most direct way. The poems bring us inside to experience and maybe understand this person so much younger than we are.

MC: Since When We Were Countries in 2010, HL has not published a more recent high school anthology. Have you noticed any particular sparks or new inspirations in the work since then? Should we be on the lookout for a fresh new voice bursting forth from the next HL high school collection?

MP: I have a very thick folder containing a draft of the next high school anthology—we’re just waiting to find the resources to publish it. The work of reaching out to the authors, updating their biographies since high school, etc., is very time consuming and the upfront cost of publishing a thick anthology is high. But I’m confident it will happen soon.

Maggie Nelson

Maggie Nelson

by Marina Chen

by Marina Chen

Jenny Qi

Jenny Qi