by James P. Lenfestey

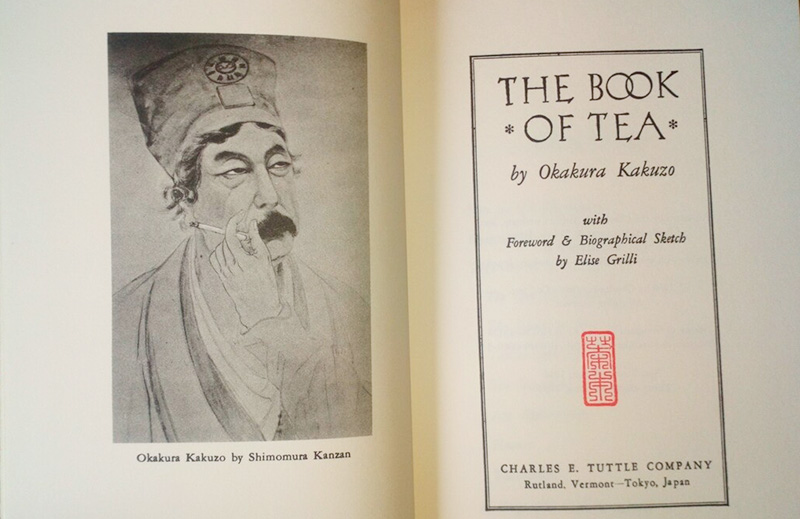

While removing books from shelves to repaint our family living room a few weeks ago, I rediscovered what was my mother’s copy of a 1956 edition of The Book of Tea. Mother was a skilled gardener and flower arranger; I saved the book from her collection for its beautiful design and feel, but had never read it. I decided I would mail it to a new friend to give to his friend, a traveling tea master—but first I sat down to glance at its contents. I slid the book from its sleeve wrapped with Japanese paper, a light moss green. My fingertips glanced along the woven silk binding to the wrapped Japanese paperboard covers, the creamy endpapers, the almost stiff pages, the inkbrush illustrations. All these drew me slowly into Kakuzo’s succinct descriptions of a two-tradition/two-continent history of philosophy, poetry, art, botany, religion, architecture, tea ceremony practice and flower arranging art, which ended only with the satisfying sadness of completion after several mornings alone with his thoughts.

The book’s stillness and understanding, useful in 1906 and after two World Wars, seem to me helpful now in coping with the unfolding dimensions of our Age of Climate Crisis and now of COVID-19. The quotations below were especially arresting to me, texts I have set beneath each chapter heading centered in boldface, as in the original. Enjoy—best perhaps with seven cups of tea.

THE CUP OF HUMANITY

Teaism is a cult founded upon the adoration of the beautiful among the sordid facts of everyday existence.

. . . when we consider how small after all the cup of human enjoyment is, how soon overflowed with tears, how easily drained to the dregs of our quenchless search for infinity, we shall not blame ourselves for making so much of the tea-cup. Mankind has done worse.

Why not consecrate us to the queen of the Camelias, and revel in the warm steam of sympathy that flows from her altar? In the liquid amber within the ivory-porcelain, the initiated may touch the sweet reticence of Confucius, the piquancy of Laotze, the ethereal aroma of Sakyamuni himself.

Those who cannot feel the littleness of great things in themselves are apt to overlook the greatness of little things in others.

Let us stop the continents from hurling epigrams at each other, and be sadder if not wiser by the mutual gain of half a hemisphere. We have developed along different lines, but there is no reason why one should not supplement the other.

The East and West, like two dragons tossed in a sea of ferment, in vain strive to regain the jewel of life . . . Meanwhile, let us have a sip of tea. The afternoon glow is brightening the bamboos, the fountains are bubbling with delight, the soughing of the pines is heard in our kettle. Let us dream of evanescence, and linger in the beautiful foolishness of things.

THE SCHOOLS OF TEA

Tea is a work of art and needs a master hand to bring out its noblest qualities.

With Luwuh in the middle of the eighth century we have the first apostle of tea. He was born in an age when Buddhism, Taoism and Confucianism were seeking mutual synthesis. The pantheistic symbolism of the time was urging one to mirror the Universal in the Particular. Luwuh, a poet, saw in the tea service the same harmony and order which reigned through all things.

Lotung, a T’ang poet, wrote of the 7 cups . . . The first cup moistens my lips and throat, the second cup breaks my loneliness; the third searches my barren entrails but finds therein five thousand volumes of odd ideographs. The fourth cup raises a slight perspiration – all the wrong of life passes away through my pores. At the fifth cup I am purified; the sixth cup calls me to the realm of the immortals. The seventh cup—ah, but I could take no more! I only feel the breath of cool wind that rises in my sleeves.

Among the Buddhists, the southern Zen sect, which incorporated so much of Taoist doctrines, formulated an elaborate ritual of tea. . . . It was this Zen ritual which finally developed into the Tea-ceremony of Japan in the 15th century.

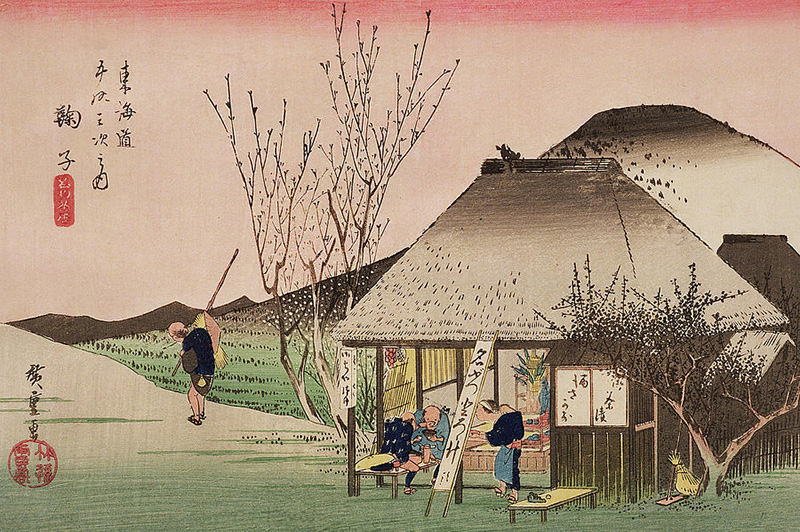

The tea-room was an oasis in the dreary waste of existence where weary travelers could meet to drink from the common spring of art appreciation.

TAOISM AND ZENNISM

Teaism was Taoism in disguise.

Teaism was Taoism in disguise.

Translation is always a treason, and as a Ming author observed, can at its best be only the reverse side of a brocade — all the threads are there, but not the subtlety of color or design. But after all, what great doctrine is there which is easy to expound? The ancient sages . . . spoke in paradoxes, for they were afraid of uttering half-truths. They began by talking like fools, and ended by making the hearer wise.

The Tao is in the passage rather than the Path. It is the spirit of cosmic change. . . . It recoils upon itself like the dragon, the beloved symbol of the Taoists. It folds and unfolds as do the clouds.

Chinese historians have always spoken of Taoism as “the art of being in the world,” for It deals with the present . . . The art of life lies in a constant readjustment to our surroundings.

Taoism accepts the mundane as it is and, unlike the Confucians and the Buddhists, tries to find beauty in our world of worry and woe.

In art the importance of the same [Taoist] principle is illustrated by the value of suggestion. In leaving something unsaid the beholder is given a chance to complete the idea and thus a great masterpiece irresistibly rivets your attention until you seem to become actually a part of it. A vacuum is there for you to enter and fill up to the full measure of your aesthetic emotion.

One Zen master defined Zen as the art of feeling the polar star in the southern sky.

To the transcendental insight of the Zen, words were but an incumbrance to thought . . . . the whole idea of Teaism is the result of this Zen conception of greatness in the smallest incidents of life. Taoism furnished the basis of aesthetic ideals, Zennism made them practical.

THE TEA ROOM

The Abode of Fancy. The Abode of Vacancy. The Abode of the Unsymmetrical.

The simplicity and purity of the tea-room resulted from emulation of the Zen monastery. . . .

. . . the roji, the garden path that leads from the machiai to the tea-room, signified the first stage of illumination – the passage into self-illumination. The roji was intended to break connection with the outside world, and to produce a fresh sensation conducive to the full enjoyment of aestheticism in the tea-room itself.

What Rikiu demanded was not cleanliness alone, but the beautiful and the natural too.

Zennism, with the Buddhist theory of evanescence and its demands of the mastery of spirit over matter, recognized the house only as a temporary refuge for the body. The body itself was but a hut in the wilderness, a flimsy shelter made by tying together the grasses that grew around – when these ceased to be bound together they again became resolved into the original waste.

Art, to be fully appreciated, must be true to contemporaneous life. It is not that we should ignore the claims of posterity, but that we should try to assimilate them into our consciousness.

In the tea-room the fear of repetition is a constant presence.

The simplicity of the tea-room and its freedom from vulgarity make it truly a sanctuary against the vexations of the outer world.

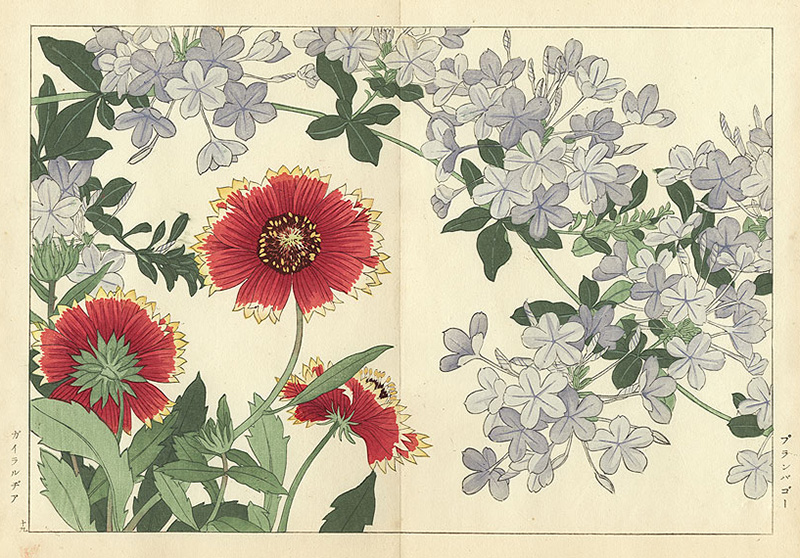

The Red Parrot by Ito Jakuchu

ART APPRECIATION

Our mind is the canvas on which the artists lay their colours; the pigments are our emotions; their chiaroscuro the light of joy, the shadow of sadness. The masterpiece is of ourselves, as we are of the masterpiece.

The masters are immortal because their love and fears live in us over and over. It is rather the soul, than the hand, the man than the technique, which appeals to us, – the more human the call the deeper our response.

Nothing is more hallowing that the union of kindred spirits in art. At the moment of meeting the art lover transcends himself. At once he is and is not. He catches a glimpse of Infinity but words cannot voice his delight, for his eye has no tongue. Freed from the fetters of matter, his spirit moves in the rhythm of things. It is thus that art is akin to religion and ennobles mankind. It is this which makes a masterpiece something sacred.

It is much to be regretted that so much of the apparent enthusiasm of art in the present day has no foundation in real feeling.

We are destroying art in destroying the beautiful in life. Would that some great wizard might from the stem of society shape a mighty harp whose strings would resound to the touch of genius.

FLOWERS

In joy or in sadness, flowers are our constant friends. . . . We have even attempted to speak in the language of flowers . . . It frightens one to conceive of a world bereft of their presence.

When we are laid low in the dust it is they who linger in sorrow over our graves.

. . . the supreme idol, ourselves! Our god is great, and money is his Prophet! We devastate nature in order to make sacrifice to him. We boast that we have conquered Matter and forget that it is Matter that has enslaved us. What atrocities do we not perpetrate in the name of culture and refinement!

Tell me, gentle flowers, teardrops of the stars standing in the garden, nodding your heads to the bees as they sing of the dew and the sunbeams, are you aware of the fearful doom that awaits you?

Why were the flowers born so beautiful yet so hapless? . . . The only flower known to have wings is the butterfly; all others stand helpless before the destroyer.

The ideal lover of flowers is he who visits them in their native haunts, like Taoyuen-ming who sat before a broken bamboo fence in converse with the wild Chrysanthemum.

Change is the only Eternal – why not as welcome Death as Life?

The tea-master deems his duty ended with the selection of the flowers, and leaves them to tell their own story.

TEA-MASTERS

In religion the Future is behind us. In art the Present is eternal.

He only who has lived with beauty can die beautifully.