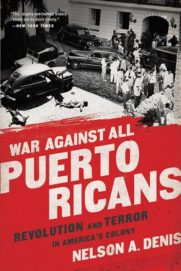

Nelson A. Denis

Nation Books ($17.99)

by Spencer Dew

The first so-called democratically elected governor of Puerto Rico, Nelson A. Denis tells us in this necessary book, smoked opium and was doubly controlled by the drug. The pipe dulled his spirit and the U.S. government blackmailed him with evidence of his addiction. Denis could make more of this valence: the oppressed wallowing in the transitory pleasures of oppression, compliant under the boot of the colonizer, complicit in helping to crush those of his fellows who attempt to resist. Yet Denis’s book is a work of history—essential history, to be sure—and he refrains from speculation about possible paths forward, even though this is the question demanded by each page of this chronicle of horror: How can Puerto Rico be free?

Puerto Ricans are called American citizens, but the term is inaccurate. Puerto Ricans are denied the full legal protections of Constitutional subjects. They can vote in American presidential elections only if they abandon the island and move to the U.S., yet they can be (and have been, in massive numbers) drafted into the U.S. armed services. It is difficult not to see the production of troops as one of the chief rationales behind the American colony of Puerto Rico, along with its strategic location and, perhaps most importantly today, its role as a captive consumer base.

The island is not patrolled by occupation forces; rather, colonial control here is primarily economic. The island has more Wal-Mart outlets per mile than any other place on earth. Any product that enters or leaves Puerto Rico is required by U.S. law to be carried on U.S. ships. Major marine freight companies thus unload and reload shipments to Puerto Rico in Jacksonville, Florida (a boon for America, in terms of jobs; an extra expense for our colonial subjects on the island). The price of certain commodities (automobiles, sure, but also produce) are higher than in the U.S., as is the cost of living, though the per-capita income on the island is less than half that of the poorest U.S. state. The island’s government, barred by law from filing for Chapter 9 bankruptcy, faces a debt crisis totaling $72 billion.

It is to this situation that Denis’s book speaks, and it is because of this situation that the book proves so difficult to review. The response inspired by War Against All Puerto Ricans is visceral: rage, guilt, despair, fear. It is hard to believe in the ideals of American democracy, the transformative promise of American law, when learning the details of a history of American conquest and oppression. American governments, American officials, and American laws, after all, banned the use of Spanish in Puerto Rican public schools, made it a felony even to own a Puerto Rican flag, and responded with violence to peaceful protests—not only machine-gunning “American citizens” in Ponce but using Air Force planes to bomb “American citizens” in two towns. Denis’s title is not a hyperbole; it is a quotation, a description of policy. He tells a story of American political and business leaders intent on owning the island, setting the Federal Bureau of Investigation to subjugate the Puerto Rican people through blackmail and terror (over 100,000 Puerto Ricans were subjects of carpetas, or secret files), and using the legal system to smash organized dissent with the arrest of thousands of nationalists. This history is largely unknown within the States, and in those cases when its contours are familiar, the dominant gloss of the perpetrators, that this was all just an “incident between Puerto Ricans” prevails.

In truth, the Puerto Rican Revolution of 1950, the main focus of Denis’s book, was a cry for international attention, a plea for recognition and justice. Wildly asymmetrical, including an assassination attempt on President Truman and a three-hour gunfight between a lone barber and dozens of police and U.S. National Guardsmen, the attempt failed and continues to fail. As a case in point, the Kirkus Review coverage of this book calls it a “relentless chronicle of a despicable part of past American foreign policy,” as if the oppression of the Puerto Rican people were behind us and Denis’s book were not an indictment of ongoing American policy. Indeed, this book is particularly urgent now. If this electoral season (for president, in the US; for governor, on the island) is to offer anything more than a contest of popular appeal and private funding, this book must play a role—this is a history of which all candidates should be informed and a present question to which they all must respond.

Which returns us, again, to the problem of a path forward, and the difficulty of writing this review. Is Puerto Rico’s situation not, like that of an opium addict, intractable? Visiting the island, I was shocked by the predominance of American retailers and fast food franchises. As PR-1 cuts south through the island and rises into the mountains, the billboards rise higher. The project of U.S. colonialism cannot be divorced from the project of U.S. corporate capitalism, and it is this drug—for it surely is a drug—that Puerto Ricans are happily consuming even as their island falls apart. American politicians, with American legislation, could take steps to relieve the island’s immediate financial crisis and should, indeed, pave the way for a free nation of Puerto Rico. But it will be an audacious task for Puerto Ricans to gain for themselves something resembling true freedom, addicted as they are to an American economic model sufficiently crippling on its own, even liberated from the draconian restrictions and penalties of the Jones Act. While there is ample reason to be deeply pessimistic about the island’s future, I also have to feel that the revolution Puerto Rico needs would offer a model for the world and that history has put Puerto Rico in the unenviable but privileged situation of confronting, years before the United States will have to, the utterly destructive force of late stage capitalism. The island may simply stumble forward, into infrastructure collapse, increasing segregation by class, walled foreign enclaves, and the eventual transformation into a narco-state. Or Puerto Rico could offer a model for the world, drawing on the same values and models of community the nationalists in this book celebrated and embodied.

I am too wary to end on an optimistic note, but Denis, whether due to editorial pressures or simply out of a sense that some catharsis was needed after so much recounting of insurmountable oppression, highlights the heroic side of the lost revolution. He gives us a Pedro Albizu Campos ready for canonization, insisting that the island is not for sale and later saying that “According to the Yankees owning one person makes you a scoundrel, but owning a nation makes you a colonial benefactor.” He reminds us of General Smedley Butler, author of War is a Racket and “I Was a Gangster for Capitalism”—works well worthy of reprinting and rereading. And he gives us page after page of play-by-play with that aforementioned barber, Vidal Santiago Diaz, who engages the government in an operatic one-man shootout, with Albizu Campos speeches blaring from a radio and Santiago Diaz himself singing politically tweaked versions of “traditional Christmas aguinaldo,” each verse punctuated with a pistol shot.

If the reader can close this book placated by some imagined solidarity with a futile last stand against an enslaving political and economic hegemony, then Denis will have failed. Canonizing these nationalists, like canonizing anyone, is a trap. In my hometown, Chicago—the distance of which from the island, as Puerto Rican nationalists in that city are quick to note, allows for a certain freedom of political imagination—there is a mural of Albizu Campos crucified. He is about to be pierced through the side by that first “democratically elected” governor of the island, the opium addict. This image—liberty beaten and bound, the deathblow to be delivered by complicity and stoned indifference—seems a far more apt image to carry away from this book. This book, after all, is not entertainment; it is an indictment and a call to action.