Max Porter

Graywolf Press ($25)

by Sam Downs

As the teenage protagonist of Max Porter’s latest novel sneaks out of his boarding school and into the night, he recalls an admissions official’s admonishment. “Is this you? The whole of you?” the administrator remarks, presumably brandishing a stiff finger to the eponymous Shy’s impressive juvenile record: “Failed 11+. Expelled from two schools. First caution in 1992 aged thirteen. First arrest aged fifteen.” By sixteen, he has “sprayed, snorted, smoked, sworn, stolen, cut, punched, run, jumped, crashed an Escort, smashed up a shop, trashed a house, broken a nose, stabbed his stepdad’s finger” and, as consequence, been sent for amendment at the Last Chance home for “very disturbed young men.” Recognizable to those who have suffered under the yoke of misdirected adults in administrative positions, the educator’s ironic advice is that Shy ought not to let his past offenses define him—while emphasizing the very idea that they do.

A teenager in mid-nineties England dealing with issues the adults in his life are unable to define, Shy doesn’t have the benefit of hindsight. Not having wanted to attend the school in the first place, and not seeming to agree with descriptions of him as a “ghost,” mad, and a “Jekyll and Hyde,” he has nonetheless taken to heart the message of Last Chance—that is, it’s his, and he’d better not screw it up. On his midnight mission, Shy heads in the direction of a nearby pond carrying a backpack heavy with rocks.

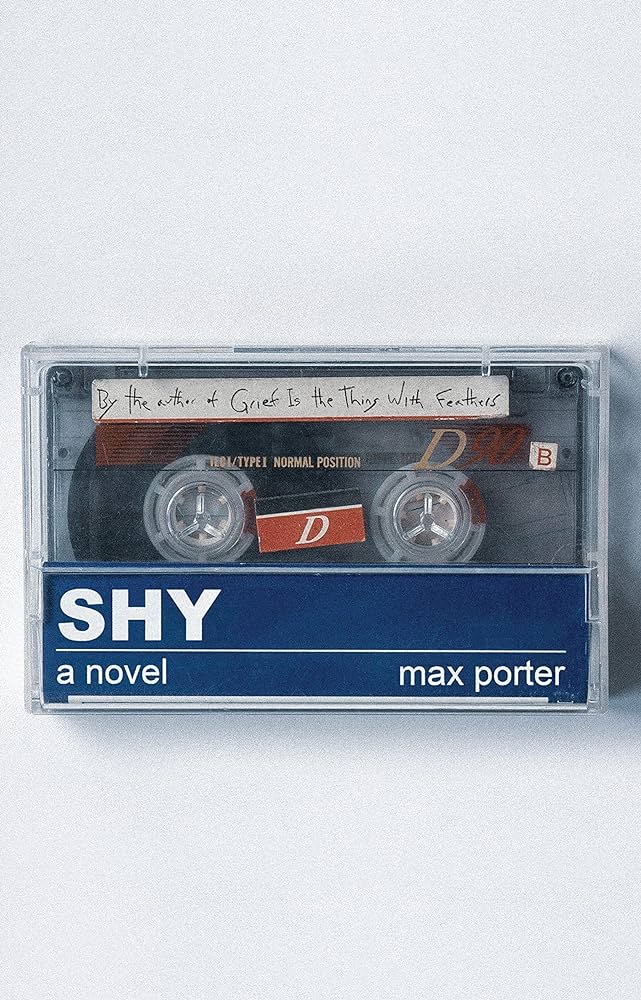

As reviews have noted, Porter’s work often attempts to fill the silences that characterize male hardship. In Grief is the Thing with Feathers (Graywolf, 2016), a widower and his sons reckon with woe transfigured into a clever, protective crow; in The Death of Francis Bacon (Faber & Faber, 2021), the final fuses of a painter’s intellect ignite as he lays dying; and in 2019’s Booker Prize Long-Listed Lanny (Faber & Faber), the anthropomorphic socioenvironmental history of a village bears down on an uncannily talented young boy. All three novels are like fifteen-minute funerals: communal, convention-busting, and packing far more emotional weight than their brevity suggests. With its tender and big-hearted story, Shy marks another development in Porter’s singular, polyphonic style, distinguishing itself as his most urgent book yet.

The late aughts saw social and political discussions about men begin to reflect scholarship about the relationship between long-celebrated masculine tenets (hyper-independence, emotional invulnerability) and violent or otherwise antisocial behavior. If the laundry list is still being written, the major garments are worth airing out: worldwide, boys fight more frequently than girls at school; men commit virtually all sexual violence; and teenage boys are between two and four times as likely as their female peers to die by suicide—a statistic made darkly ironic by the American Right’s eagerness to foist liability for gun violence upon the mentally-ill, since the actual demographic uniting some 98% of mass shooters of gun violence is their maleness. Meanwhile, anti-intellectual opposition seems to have stalled the necessary turn from diagnosis to remedy, as can be seen in how useful terms like “toxic masculinity” and “mansplaining” have been hollowed of their original intent by offhand, uncritical usage.

A 2023 New Yorker article title emphasizes the extraordinary breadth of The Problem: “What’s the Matter with Men?” This could rightly serve as the slogan for Last Chance, but as well-meaning as the staff may be, their laser focus on obliquely diagnosing the boys’ troubles without providing sensible solutions leaves the likes of Shy unmoored. Faulting him for that would be like faulting a lost hiker whose guide had only shouted, “Don’t get lost!” As Porter portrays Shy’s vast, dynamic individuality in stark contrast to the reductive thinking that persists to this day, the conclusion settles in that neither Shy the book nor Shy the boy are so strange after all, however much they may defy our initial expectations. Who, after all, hasn’t spent a few youthful hours feeling lost, searching, considering escape? Who hasn’t thought, graspingly, “the night is huge and it hurts”?

Like Porter’s previous work, Shy offers a message about the human risk of minimizing the unknown by viewing it through the lens of the known. As Carmen Maria Machado states in her masterful memoir In the Dream House (Graywolf, 2019), “Putting language to something for which you have no language is no easy feat.” Perhaps the same can be said of putting language to something, or someone, for which you have too much language, and too much of it inexact.

Click below to purchase this book through Bookshop and support your local independent bookstore:

Rain Taxi Online Edition Fall 2023 | © Rain Taxi, Inc. 2023