by Eric Lorberer

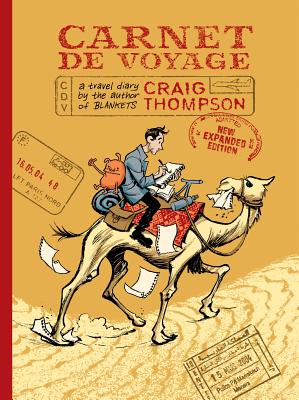

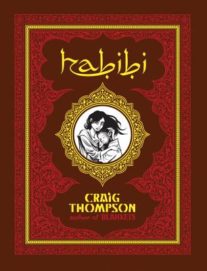

Earlier this year, Craig Thompson’s 2004 book Carnet de Voyage, originally published by Top Shelf Productions, was reissued by Drawn & Quarterly in an expanded hardcover edition. Thompson, an internationally celebrated cartoonist, is the author of books such as Good-bye, Chunky Rice, Blankets, Habibi, and Space Dumplins, but Carnet de Voyage is unique among his works in many ways, not the least of which is that it is real-time drawn work of nonfiction. In the following conversation—a transcript of a public conversation held on August 18 as part of the 2018 Autoptic Festival, a comic and independent print culture gathering in Minneapolis—Thompson discusses the book and its world with Rain Taxi editor Eric Lorberer. (The transcript has been lightly edited by the participants for clarity; images provided by Craig Thompson.)

Eric Lorberer: Carnet de Voyage feels like an utterly unique book, and for that reason I think it is my favorite of your books, although that’s a tough call. How did you come to imagine the project?

Eric Lorberer: Carnet de Voyage feels like an utterly unique book, and for that reason I think it is my favorite of your books, although that’s a tough call. How did you come to imagine the project?

Craig Thompson: The book is sort of embedded where I was emotionally at the time. And the new edition has some new material in it and it has some pages about how the book came to be. I was living in Portland, Oregon and I was just going through a weird space in time like a lot of people who are about to set out on some sort of voyage. I knew I needed to get out of Portland for a while so I set up this month-long travel adventure in Europe where I have a bunch of friends. I was going to go catch up with them and then my European publishers caught wind that I was going to be in France and it started turning into a book tour, and suddenly it was three months long. The advantage of that is that they were kind of paying for my tickets. I kind of had this sort of couch surfing adventure mapped out, and they said okay, we’ll fly you here and here and pay for your flight to Europe . . . But suddenly it was co-opted and it turned into a book tour. And that was not my intent, so then I carved out three weeks just for myself in Morocco. It was the very beginning of me working on Habibi; it was sort of in the conceptual stage, I hadn’t started writing, but I was thinking about Islam and thought I should probably go to an Islamic country, and Morocco just happened to be the easiest to go to both geographically and culturally. So suddenly I had this three-month trip planned and I felt like I would go crazy if I didn’t have a creative project to ground myself, because I am so focused all the time on working—I’ve never taken a vacation in my life, how can I take three months off? So then I talked to my publisher at the time, Top Shelf, and was like “hey, I am going to go on this trip and I am going to keep a comics diary, do you think that’s something we could publish maybe down the road if it turns out?” And they said “better yet, let’s publish it before you get home from your trip.” So then there was this crazy component where I had to send it to press midway through my travel—and sure enough, before I got home, the book was in print.

EL: Yeah, it’s one of the really special things about this book—as the reader you approach the ending and you realize this is happening in real time, or at least the illusion is that it is.

CT: No no, it is real time.

EL: Well I wanted to ask about that, because we also hear or we witness in the diary that you’re making other sketches, you’re giving away portraits to people . . . so we have some sense that the composition process is at work. Because if these pages are a direct printing and what you do in your sketchbook—I mean, that’s incredible.

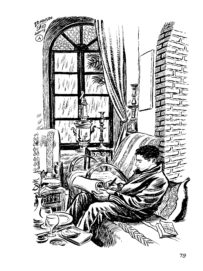

CT: It is a direct printing of what I did in my sketchbook; maybe half of the book is sketches straight to paper while looking at the subject, portraits of people or the streets, and then the other half are comics pages that are more composed—but in real time. And when I was composing them I was on trains and planes and buses or in my hotel room late at night in a dim light—you know, skipping sleep so that I could make some comics pages about what happened that day.

EL: And also skipping interactions with people, or taking a break from the actual living of life . . .

CT: Yeah, it both helped me engage with people and also distanced me from people. It bridges a certain communication barrier because I was in Morocco where I didn’t speak Arabic or French or Spanish, and I was in all these other European countries where I didn’t speak the language, so it helps me sort of have a connection with people or speak through drawings. But other times I was just sketching all the time, every meal, every spare moment. I grew up in Wisconsin, so that sort of Midwestern work ethic was ingrained in me. I didn’t know how to take a vacation—that was my first vacation of my life!

EL: You mentioned how the Morocco section feeds into Habibi, and we know now what we didn’t know then—the reader of this book when it came out originally was still in awe of Blankets and immersed in that experience, in that persona of yours, and you kind of address that—that’s the tour you’re on, and the sort of comics fellowship you’re being welcomed into is largely based on that. But now we see that the next book was gestating already, and I wondered if you say a little more about that.

EL: You mentioned how the Morocco section feeds into Habibi, and we know now what we didn’t know then—the reader of this book when it came out originally was still in awe of Blankets and immersed in that experience, in that persona of yours, and you kind of address that—that’s the tour you’re on, and the sort of comics fellowship you’re being welcomed into is largely based on that. But now we see that the next book was gestating already, and I wondered if you say a little more about that.

CT: Well, I definitely am like a naive Country Bumpkin in this book—I’m 28 years old, I haven’t really travelled or experienced other cultures, and this whole book tour thing is overwhelming to me . . . now it’s sort of old hat and I’m a little cynical about it, though with that said I am super honored to be here today. I like touring a lot but I am much more cool with it now than I was then, because I hadn’t yet had any success with my books, so my big book tour in Europe—every moment was kind of awe golly, there’s a lot of that in this book.

EL: Yeah, you have a scene in here where you’re remembering a book signing appearance you made for Goodbye, Chunky Rice probably, and like four people show up—so it is a little meta-textual here, that one of the themes in Carnet is being an author on tour, and now we’re talking about that.

CT: Which is a little embarrassing! I would never do a book like that again partly because I don’t think it’s that interesting to document a book tour. I also think it’s pretty crazy to try to create a book while doing all the book signings and promotions. But I am grateful for it for that reason, because it was a crazy thing that I’ll never do again, and I haven’t seen other cartoonists be able to manage the combo. I guess as a reader I have a voyeuristic interest in what it is like for an author on tour.

EL: It’s funny, my memory of the book was how deeply solitary and personal it was, even though you’re also seeing friends and engaging with lots of people, and there’s an obvious pleasure and excitement to that—but you’re a solitary traveler, and you’re coming off a breakup, and you’re often alone in your head. But then again, you’re not actually alone because you have invented a travel companion in the book called Zacchaeus. How did you come up with that?

CT: I see that there are a couple kids in the audience: Zacchaeus, the little orange critter on the cover, ends up having a big role in my children’s sci-fi adventure book Space Dumplins. This is where he first emerged and he was sort of the other part of my conscience or my personality in this book—I am very emo, kind of fragile and whiny, which is definitely part of my personality, but then there is the more scrappy, more Midwestern, “pick yourself up by your boot straps and stop whining” voice that’s always with me, or like “lighten up and have fun, don’t be heavy all the time.” It’s just the counterbalance to that other part of my personality, sort of a Jiminy Cricket—although I guess Jiminy Cricket is maybe more of a moral conscience; Zacchaeus is a little more sassy.

CT: I see that there are a couple kids in the audience: Zacchaeus, the little orange critter on the cover, ends up having a big role in my children’s sci-fi adventure book Space Dumplins. This is where he first emerged and he was sort of the other part of my conscience or my personality in this book—I am very emo, kind of fragile and whiny, which is definitely part of my personality, but then there is the more scrappy, more Midwestern, “pick yourself up by your boot straps and stop whining” voice that’s always with me, or like “lighten up and have fun, don’t be heavy all the time.” It’s just the counterbalance to that other part of my personality, sort of a Jiminy Cricket—although I guess Jiminy Cricket is maybe more of a moral conscience; Zacchaeus is a little more sassy.

EL: It reminded me of Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials trilogy; I don’t know if you’ve read that but the concept there is that every person has a daemon, a sort of animal companion that is a reflection of their inner self. Zacchaeus is yours for sure! On the topic of writing autobiographically, it’s interesting you quote Blutch saying that doing autobiographical comics can really mess with your life—that line has a lot of weight in what is essentially a day to day recounting of what’s happening. What is your perspective on that now?

CT: There’s a problem when doing an autobiographical work because you’re free to tell your own story, but wherever it touches with other people’s personal lives then it gets very sketchy. Lewis Trondheim was telling me when we were gossiping about another French cartoonist, Joann Sfar, that every conversation that Joann has with his friends ends up in his comics—he’s been totally destroying their privacy, taking their personal stories and putting them in his books, so he’s lost a lot of friends. And Lewis and I had this very intimate conversation that was really profound—I thought oh man, this is some good stuff I should put in the book—but as I was thinking that, I realized that there’s a lot of Lewis’s personal information in this story, so I couldn’t draw that. It’s frustrating when you’re doing non-fiction, because unless you’re a total jerk, you know you kind of have to protect those things. I think one of the reasons it comes off very interior and whiny is because that was the only material I was really free to put out there, my thoughts and feelings. I think it’s true that you can have more truth in fiction. That’s one of the things Blutch was saying, something like “all my work is personal and truthful, although it’s completely made up”—that’s where he finds honesty.

EL: In the scenes of you visiting with them we see how welcomed you were by the fraternity of European cartoonists—they must’ve been an influence on you, but you became their peer. I thought it might be interesting to hear about that transition.

CT: I was lucky to be one of the first young American cartoonists that was having a dialogue in the European scene, especially with French cartoonists, but they were equally influenced by the American indie comics movement, people like Dan Clowes, and the Hernandez brothers, and Julie Doucet. They were being influenced by ’80s and ’90s North American indie comics and then they started to make these amazing books that collectively kind of took it to the next level. I ripped off a lot of my ideas from them, especially from the French publisher L’Association; even the format for the original Carnet I stole from them. I think my style borrowed very heavily from Blutch, and Trondheim, but I wasn’t seeing that work here—graphic novels were not a thing then. Trondheim did a 500-page graphic novel (Lapinot et les Carottes de Patagonie) and he didn’t know how to draw before he started the book, he challenged himself: “I’m going to draw 500 pages, and if I can’t learn to draw by that time then I’ll move on and do something else.” And that was his first published book. I was like “Oh, I’m gonna steal that idea,” and that was Blankets—it was totally borrowed from his example.

CT: I was lucky to be one of the first young American cartoonists that was having a dialogue in the European scene, especially with French cartoonists, but they were equally influenced by the American indie comics movement, people like Dan Clowes, and the Hernandez brothers, and Julie Doucet. They were being influenced by ’80s and ’90s North American indie comics and then they started to make these amazing books that collectively kind of took it to the next level. I ripped off a lot of my ideas from them, especially from the French publisher L’Association; even the format for the original Carnet I stole from them. I think my style borrowed very heavily from Blutch, and Trondheim, but I wasn’t seeing that work here—graphic novels were not a thing then. Trondheim did a 500-page graphic novel (Lapinot et les Carottes de Patagonie) and he didn’t know how to draw before he started the book, he challenged himself: “I’m going to draw 500 pages, and if I can’t learn to draw by that time then I’ll move on and do something else.” And that was his first published book. I was like “Oh, I’m gonna steal that idea,” and that was Blankets—it was totally borrowed from his example.

EL: Yeah, even the format—I mean when you came on the scene it was pretty unusual for someone not to have serialized a work of that length first.

CT: I don’t know if there were any, I can’t think of any examples offhand. Of course Fun Home came out like a year after that, and Alison Bechdel had been working on that for like 10 years. It was kind of a moment of things shifting in the comic scene.

EL: One impression a reader might get is that the comics medium offers its creators a more global enterprise than maybe other book forms do. Do you think that’s true?

CT: That’s completely true. In the year 2000, L’Association published this 2000-page wordless comics anthology, did you ever see that book?

EL: No.

CT: They put out an international call for contributors and the only requirement was that submissions had to be wordless; there were people from all over the world in that anthology, and that was my introduction to a lot of those people. I regretted not sending in something myself—I remember seeing the call for submissions and thinking “oh, I’m not good enough to contribute,” but then it ended up being pretty inclusive. They only printed 2000 copies, so it’s pretty rare.

EL: I think that sort of dovetails with a moment that we’re in now—travel really makes obvious how Americans are regarded in all sorts of ways, culturally and politically maybe the most, and you touch on this in the book. There’s a moment when you almost guiltily admit after the weeks in Morocco that its sort of a relief to be among Europeans again, sort of demonstrating that stress. Given what’s going on now in our country concerning immigration, does that come back to you in any way with republishing this book?

CT: Hmm, that’s always a dilemma traveling, and it was new to me at that time. I encountered a very fair perception of the U.S. internationally, and you know I don’t support the US as a world power, I don’t support capitalism, and so a lot of times I just . . . this is such a weird, delicate thing to talk about! But I remember I went to Jordan not too long ago for the U.S. Embassy; it was related to the Syrian refugees and working with some people there. And of course being American in the Middle East, there’s a lot of accusations one hears . . . this was when Obama was still president, so they were blaming Obama, and they were blaming Americans, and I had to spend a lot of time kind of defending and explaining: this is what the American people are doing, this is what our government is doing, this is what corporations are doing . . . this is something I am always thinking about, but I am terrible at articulating. Even with my newest project, I am trying to look at globalization and how there are both positive and negative sides of it: there are really beautiful sides to global community in terms of cultural exchange, and then there is a part I don’t support at all, the exploitation that comes with capitalism.

EL: Well, I think you were articulate in that response and I’m grateful that you are willing to discuss it—it is a delicate topic, but I really believe we need authors to weigh in on such issues because people need help dealing with this. So the trajectory from this book to Habibi and maybe to your upcoming project seems to be towards a more globally inclusive picture of humanity, and I for one applaud that.

CT: Thank you.

EL: One last thing before we turn to the images; the name of the comics show here this weekend is Autoptic, an ingenious name that means among other things “seen with one’s own eyes”—and Carnet de Voyage is such a great example of that in practice. I think a lot of people assume that depictions of what is strange or foreign have to be heavily researched, and I’m sure that’s in there too, but there really is a sense of immediacy here, that this journey is from your perspective. So I just thought we’d touch on that and the amount of research that goes into your work, versus capturing what you’re seeing with your own eyes.

CT: That’s a great question and it segues pretty naturally into the images I brought. But yeah, I did this book in 2004 before I ever had a cell-phone or digital camera, so zero photos or reference material were used making the book—that’s another reason I don’t know if I’ll be able to repeat this again, because like most people I’ve become really lazy as a documentarian! So everything was just drawn straight to paper from my head. There’s a lot of missing information because I wasn’t google searching or fact checking things.

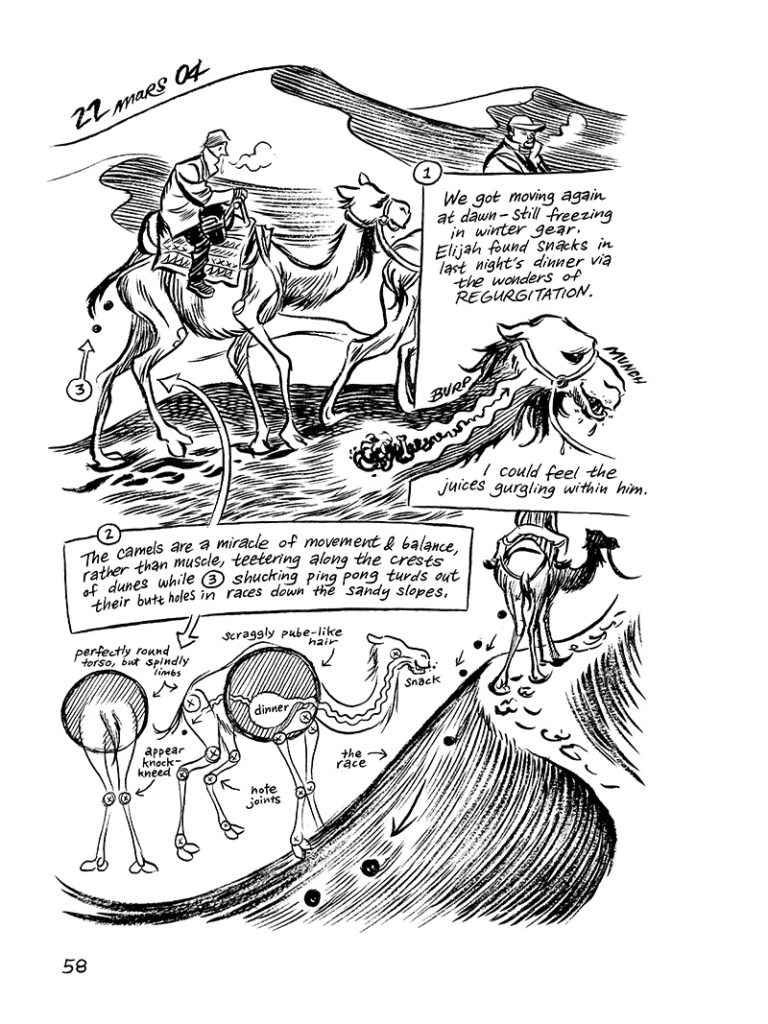

EL: Like the notion that when you’ve ridden a camel, you’ve experienced the camel’s digestive system—suddenly we’re getting your drawings of what that might look like—it’s a really fun reflection on how interiority works, when we’re really pretending to know something or in terms of it being scientifically accurate. Craig, I know the crowd probably wants to see the images at this point and so do I, so maybe we can switch to that and keep talking a bit.

CT: Okay great. (shows slide) So this is just a quick time frame of what is involved in making these books. Blankets I spent about three and a half years working on; Habibi took almost seven years to do. And Carnet de Voyage was two and half months. This is my most off the cuff, uncensored, just send it to press book I ever did. So it’s flattering that it might be your favorite of my books, but that’s sort of how I feel too, in the sense that this is my only book I didn’t labor over. It’s raw and it’s spontaneous. And as I said, I didn’t use any phones or cameras or digital things, and I’m kind of nostalgic or wistful for that time. I know that I’ve become lazier as an artist because I don’t have to draw my notes on paper.

EL: I just want to say that it’s still possible to do—if there is any cartoonist out there that wants to travel somewhere without a phone, I would read what you create!

CT: Yeah, that’d probably be a very spiritually cleansing thing to do. And I always had a sketchbook with me at all times. Here’s a photo by the way—no photos were used to make the book, but I had an analogue camera and I developed a couple rolls of film once I got back from the trip—so these are photos I developed after the book was already in print. You can see in my hand I had this sketchbook with me. And there’s those camels you were referencing—an important part of this book is that it got me out of my comfort zone. Usually when I make a graphic novel I’m just stuck in my studio all the time, but this is like, here’s some drawings I did on the back of a camel! I was on planes and trains and standing in the street with crowds around me, almost getting sunburnt and run over by donkey carts—and I’m drawing all the time. The book was comprised of three spiral bound sketch books, and a few supplemental sketch books for some of that composition work that we were talking about, where I had to figure out what a story would look like. You were asking early on “were these pretty much from your sketchbooks?” and yeah, you open up my sketchbooks and that’s what was inside.

EL: Forgive me if I’m asking a really stupid question, all these practicing cartoonists in the audience might already know the answer, but a lot of the published sketch books that I have seen have a rougher quality to the drawings—but these don’t. I guess I had assumed that’s what sketchbooks were.

CT: I’ll show you the rough part, those smaller sketch books where I would figure out what pages I was gonna draw; it was kind of like my diary, my journal. Half the drawings were just pages that I drew on location while looking at the subject, they’re portraits and landscapes, and the other half were comic pages. I realized as I was prepping photos to talk about the book that it organically falls into a three-act structure; nothing was planned but the first month was in Morocco mostly, the second month was in France with friends, and then the last third is the book tour and also a sort of idealized travel romance. And we mentioned briefly that I was just starting to conceptualize Habibi—here’s a really crude sketch of magic squares that ends up in Habibi. This is also where I was having my first real conversations about Islam, because up until that point I was pretty sheltered and isolated; I hadn’t had any friends that were Muslim and hadn’t had the necessary conversations.

EL: And you were seeking them out?

CT: Yeah, though it started randomly. Or maybe not so randomly—you also asked about people’s perception of America and stuff, and there were some awkward moments. Like when I was in Morocco I would stay in the old medina, which is a terrible place to stay; I thought it was the authentic area, but it’s probably the least authentic part of the city. It’s like staying in Tijuana when you go to Mexico—it’s all hustle and tourism and drugs, not the best place to be. When I would get out of the medina and be with regular people, I’d have better interactions and conversations; we would just talk about everything we had in common. And this ties in directly with what we were saying too: there’s all this understandable anti-American sentiment. I put some of that in the book, like when I showed some anti-American murals. Israel=Nazis — that was a pretty loaded one! But then those same kids that were hanging around there, they would invite me to their homes and I would have these amazing intimate meals with people. So despite the conflict between our countries, the overall sense was that everywhere you go, people are family. That’s what travel is about for me. Instead of putting boundaries and walls and borders, you see we’re all exactly the same wherever you go.

EL: I think a theme of your book, and of a lot of travel writings, is that you find something exhilarating in mundane day-to-day actions —everybody has to eat; everyone has to catch the next train. Everyone just has to exist. And it becomes kind of spiritual after a while, to witness those ordinary moments. I think you capture that really brilliantly and it made me reflect on how that’s actually a theme in your other books as well — the mundane and the magical are actually the same thing.

CT: Thank you. It’s always frustrated me that the comics medium tends towards fantasy and super heroes, because for me real life is much more compelling—those are the stories I always wanted to see in comics, and now we’re seeing a lot more of them, so I’m grateful for that. I think of comics as a very human and intimate medium—it’s one of the visual mediums we have that one person can create—you know, it’s not movies or television or video games, it’s something much quieter and more personal. When I did Blankets, at the time it seemed like a novelty to do a really big book where absolutely nothing happens—that’s what I would tell people I was working on. And I wanted it to take place in a very small, intimate space, like a bedroom. So likewise in Carnet, I just wanted to slow things down. Occasionally I would collage. There’s a little bit of collage—like here [shows image] I had a different drawing, it’s a full page sketch that I inserted in that blank spot—so if there is any kind of editing, it’s that kind of thing.

EL: That’s sort of a relief.

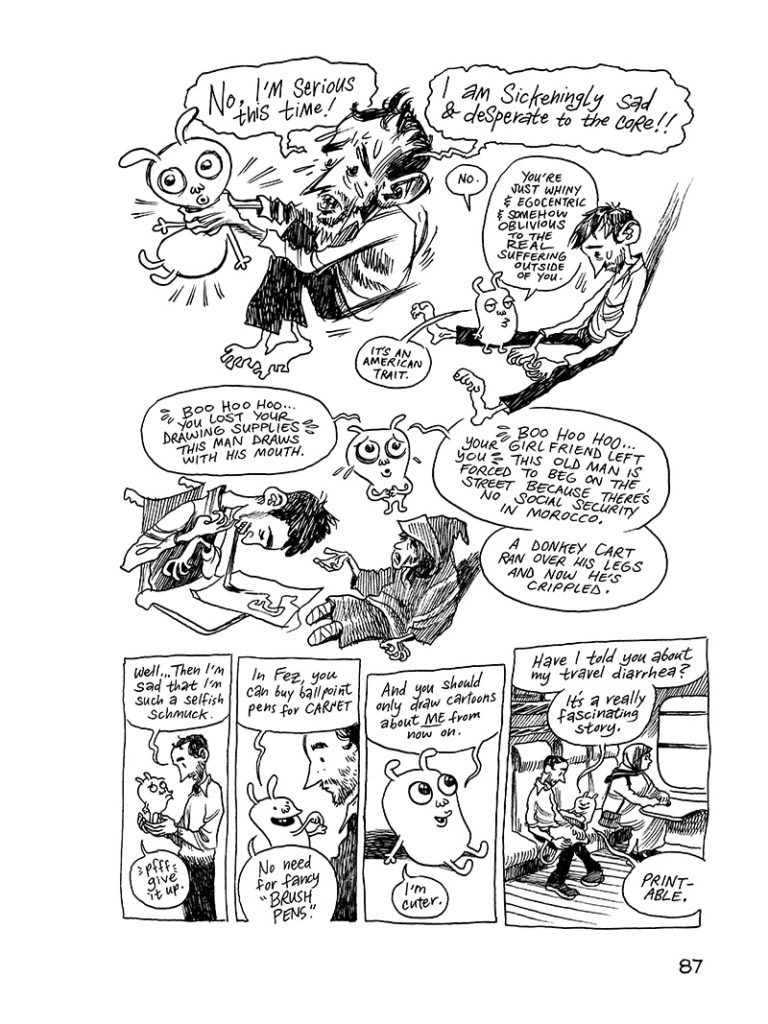

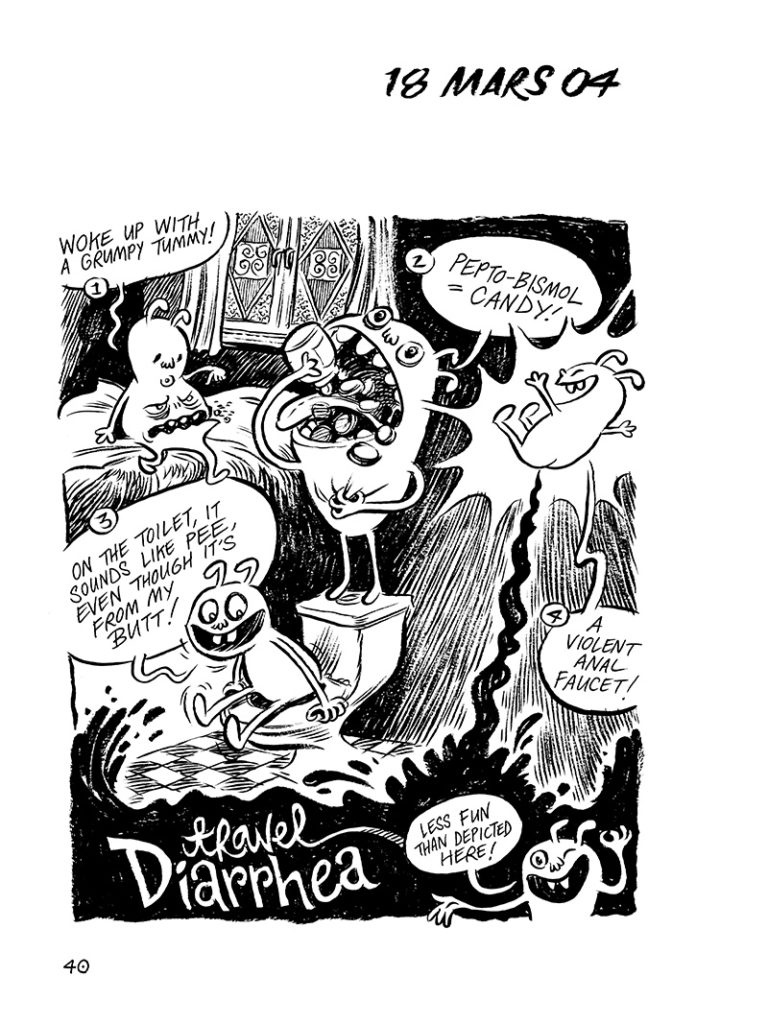

CT: Yeah, I would make drawings and collage as needed, because some of those sketch book drawings would work. I had to put in the travel diarrhea page [shows image], because there’s this scatology theme in a lot of my books too, but I think it sort of reflects this discomfort of travel.

EL: You can turn that into a poster and make a fortune, because every traveler can relate to that! And for anybody who hasn’t read it you can see Zacchaeus coming in right in the end to…

CT: Mock my whininess! This was one of those moments where I would’ve felt refreshed to hang out with Europeans. A group of Spaniards took me under their wing, and we were traveling through Fez together; I was doing drawings as I was walking around. So the drawings on the left are drawn—while walking—and then later that day I would compose a comics page. It’s amazing I didn’t step in more donkey poop or something. Some of the places were sort of chaotic and I would try to escape to some private spot on a roof top where nobody would bother me. I got in the habit of trying to get up high in places.

EL: You know, these images just make me want to point out that another tension that makes the book exciting has to do with the urban setting. You were talking about the chaos of the medina and all that, and coming after the pastoral vibe of Blankets . . . I think in here you even decide at one point, “I am a nature cartoonist. That’s really who I am in my core.” So it’s interesting that here you’re forced to depict an urban reality.

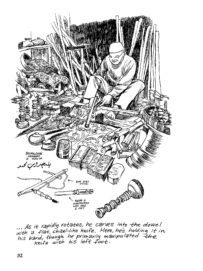

CT: Yeah, that’s a good observation. I grew up in rural Wisconsin and I don’t want to live in those places ever again, but I grew up in nature and that’s where I am most comfortable. I live in Portland now, and I live there partly because it’s near the ocean and the mountains. I want to be in a city culturally, but I need frequent escapes to actual nature—I get pretty claustrophobic when I’m in cities. The drawing on the right there is where this weird thing would happen sometimes . . . when I’m drawing in public you attract people’s attention. Usually I’d have young boys surrounding me and I’d give a lot of sketches away, so there are portraits that never made it into the book. But the butcher, he was wanting to see the image I drew of him so I walked over to show him the drawing, and he got some blood on my sketch book. While examining my sketchbook in disgust, I ran my noggin into this slab of hanging meat. And then these guys on the left—there’s no photos used, but sometimes they look like photos, because people would see me sitting there drawing so they’d strike a pose. I made good friends despite there being a language barrier. I didn’t speak Arabic or French—but like this guy Said, we just sat inside on a rainy day and we drew together all day, it was one of those great moments. There’s another guy in Marrakesh, this guy named Mohamad, he did this sort of woodworking with a foot-operated lathe spinning this dowel to make these candle sticks and stuff—and he was really happy to have me sit in front of him for like an hour and make this portrait. I don’t think I would have had that bond with him if I had just been a tourist, snapping a “aw, cute” photo—and I’m really grateful for that exchange.