Lucy Atkinson

Signal Books (£12.99/$17.34)

by Timothy Walsh

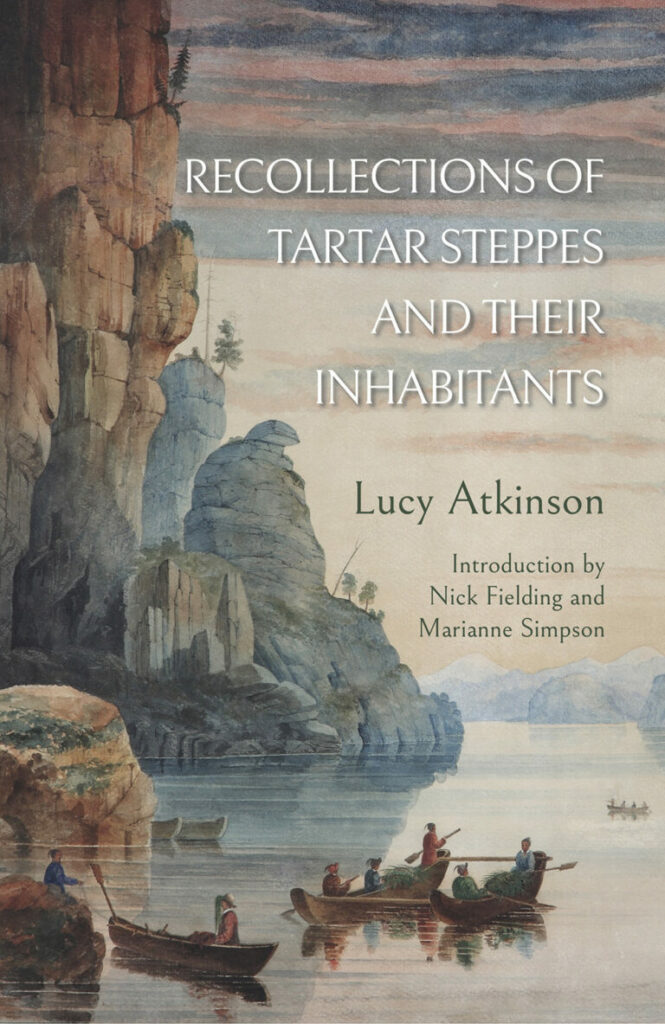

In the annals of travel and travel writing, few adventurers have been as intrepid as Lucy Atkinson—yet she has been largely forgotten. Her book, Recollections of Tartar Steppes and their Inhabitants, was originally published in 1863 in an edition of 900 and quickly slipped into oblivion, perhaps because it did not mesh with then-current conceptions of Victorian womanhood. Thankfully, a new edition just published by Signal Books restores this lost classic to print, capably edited by Nick Fielding and Marianne Simpson and with a comprehensive introduction.

In the winter of 1848, Lucy Atkinson set out from Moscow with her new husband, Thomas, on an epic journey through remote areas of Siberia, the Altai Mountains, and what is now eastern Kazakhstan. Traveling on horseback with a pair of pistols in her saddle, Lucy spent the next six years exploring this largely unknown region where “an Englishwoman was an object they had no conception of.”

The expedition’s purpose was for Thomas, an artist, to sketch and paint the wild and beautiful landscapes as they went. During the course of their journey, Lucy gave birth to their son, Alatau, during a bleak winter in the remote mountains after which he is named. As they traveled, they often stayed with nomadic Kazakhs, who moved their auls with the season, as well as with the indigenous Kalmyk and Buryat people. Her husband wrote two well-received books about their journeys, which made him something of a celebrity. Back in London, two years after her husband’s death in 1861, Lucy was persuaded by publisher John Murray to write her own memoir of those years.

Throughout Recollections of Tartar Steppes, Atkinson’s appealing personality and sharp wit shine through. Her style is vivid and engaging, her careful description often laced with ironic overtones and wry asides. She also provides a running commentary on the lamentable strictures on women in Western society as well as among the nomadic Kazakhs. The book is structured as a series of letters to an unnamed friend, a common convention of the time, which allows Atkinson to adopt a familiar, confiding tone peppered with acerbic, often humorous comments on a wide range of topics, from the comforts of sleeping in bearskins to the stultifying lives of officers’ wives in far-off outposts. The epistolary structure also allows Atkinson to skip around quite a bit and vary her focus so that, for example, an episode where she bargains with a Buryat family for a reindeer for her son to ride leads directly into a discussion of the excellence of picnics in Siberia.

Whether describing her technique for fashioning hats or the proper way to ford a raging river on horseback, Atkinson is refreshingly modest even as the reader grows ever more astounded by her resourcefulness and courage. Atkinson is also particularly observant of the customs and dress of the women she meets. Here she is describing a young Kazakh woman:

The younger one was a very pretty girl, with large black eyes; she excited both my interest and curiosity. Her dress was composed of striped silk of various colours, in form like a dressing-gown, and tied round the waist with a magnificent shawl; she had on black velvet trousers and boots, her hair was braided into a multitude of plaits, each one of which was ornamented with coins of various kinds, silver and copper, some even of gold: thus the young lady carried her fortune about with her.

For the first hundred pages or so, as she recounts a journey of thousands of miles on horseback, Atkinson gives no hint that she was, in fact, pregnant. It is only after the harrowing premature birth of her son that she coyly mentions his arrival:

Here I have a little family history to relate. You must understand that I was in expectation of a little stranger, whom I thought might arrive about the end of December or the beginning of January; expecting to return to civilisation, I had not thought of preparing anything for him, when, lo! and behold, on the 4th November, at twenty minutes past four pm, he made his appearance.

Besides being a stirring adventure story, Atkinson’s memoir is also a rare firsthand chronicle of a time when the Russian Empire was in the process of constructing forts ever-farther southward in the early stages of the “Great Game” that was to accelerate later in the nineteenth century. Atkinson also extensively chronicles the ways of the Kazakh people at a time when their nomadic lifestyle was just beginning to be threatened by the incursions of the Russian Empire (and which would be outlawed under the Soviet Union, leading to mass starvation in the 1930s). As the Atkinsons travel through remote areas of Siberia, Lucy also recounts their many visits with the famous Decembrist exiles, banished by the Czar in 1826 when their plans for a coup were revealed.

This new edition of Atkinson’s memoir includes a comprehensive introduction that greatly extends our knowledge of Lucy and Thomas, both before and after their travels—not long ago, not even Lucy’s maiden name was known. Excellent as the introduction is, there is one problematic editorial decision: Throughout her memoir, Atkinson refers to the “Kirghis steppe” or a “Kirghis yurt” or a group of “Kirghis riders” when, in fact, she is referring to Kazakhs. This was a universal usage (and mistake) in the nineteenth century and well into the twentieth, when Westerners made no distinction between the Kazakhs and the Kyrgyz who lived farther south in what is now Kyrgyzstan (and also because “Kazakh” was too easily confused with “Cossack,” two very different groups whose names derive from the same etymological root). The editors briefly explain this, but then go on to “correct” all of Atkinson’s references to “Kirghis,” substituting “Kazakh” instead within Atkinson’s memoir. This is a dubious decision at best. Atkinson never once used the term “Kazakh” in her memoir, and it would have been an alien term to her when writing in 1863.

The fact is that Lucy and Thomas traveled with and lived among the Kazakhs for years—but always referred to them as Kirghis, as did all their contemporaries. This kind of misappelation, universal as it was for well over a century, is significant in itself and should not have been “corrected” in an historical text. While the editors’ emendation might lessen a general readers’ confusion, it also conceals a very suggestive and significant fact. The inaccurate use of “Kirghis” says a lot about the knowledge, attitudes, and preconceptions of Westerners exploring Central Asia in those times. A more detailed note about this was called for from the editors, but the text itself should not have been altered.

This caveat aside, the editors do provide a richly detailed account of Lucy’s early life and her struggles after the death of Thomas. Atkinson’s ensuing legal battle with her husband’s first wife has enough plot twists and skullduggery to be worthy of a Dickensian novel and makes for absorbing reading. The introduction weighs in at seventy pages, though, so first-time readers of Atkinson’s memoir—nearly all readers—would be well advised to read just the jacket flap copy and the first three pages of the introduction before diving into the memoir itself. Only then will the reader be prepared to appreciate the many revelations in the introduction, including the strange circumstances that lead to Thomas not being able to even mention Lucy and their son in his two books about their travels.

Much of the material in the introduction is based on new discoveries in archives and on Thomas Atkinson’s extensive journals, which became available only recently. The editors of this new edition go well beyond John Massey Stewart’s useful but flawed book on the Atkinsons, Thomas, Lucy & Alatau (Unicorn, 2018). Whereas Massey Stewart is too often given to unfounded speculation based on inadequate research, Fielding and Simpson present a balanced and detailed portrait of one of the most interesting and daring couples of the nineteenth century. This new introduction, together with the material on Fielding’s website dedicated to the Atkinsons (siberiansteppes.com) and his previous book on the Atkinsons, South to the Great Steppe (First, 2015), now comprise a firm foundation for all future research on this historically significant couple. For the general reader, though, it is Atkinson’s engaging and effervescent memoir itself that will be of primary interest.

Rain Taxi Online Edition Summer 2022 | © Rain Taxi, Inc. 2022