The Photograph as Evidence

The Photograph as Evidence

Sandra S. Phillips, Mark Haworth-Booth, and Carol

Squiers

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art/Chronicle Books ($24.95

by C. K. Hubbuch

The invention of photography in the mid-nineteenth century changed forever the way we view the world. Unlike previous methods of visual representation, the photograph is mechanical; with the simple momentary opening of a shutter and the application of a few chemicals, appears a seemingly exact two-dimensional representation of whatever was before the box. Presumably unflinching, accurate, and objective, photography, in spite of the hocus-pocus nature of its process, seemed (and to some extent still seems) an indisputable reflection of reality—a "just the facts, ma'am" sort of medium. In the eponymous catalog for the 1997 exhibit at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Police Pictures: The Photograph as Evidence, Sandra S. Phillips, Mark Haworth-Booth, and Carol Squiers discuss the concomitant adaptation of the photograph to use as police evidence.

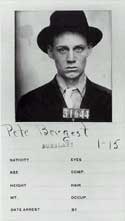

In many ways photography is synonymous with police work. Case in point: the mug shot. The mere publication of the photographic documentation of an apprehended suspect—guilty or not—suggests criminality. Since its earliest uses in the late nineteenth century, through its heyday in the gangland era of 1930s America, up to the present, the forensic photo, with its stark lighting, still life composition, and often overhead point-of-view, has held the status of incontrovertible evidence. "Photography," writes Phillips in her essay "Identifying the Criminal," "was seen to embody the new authority of empiricism." Or, as Haworth-Booth quotes from an 1857 article in the Quarterly Review, photography, while maybe not fulfilling the day's requirements for fine art, satisfied "the craving, or rather necessity for cheap, prompt, and correct facts."

With more than 100 photographs, curator Sandra Phillips has documented both how photography has altered the way we perceive crime and the criminal, and the way in which the "photograph as evidence" has colored how we are expected to understand the photograph: an impartial record of reality. The origins of police photography, however, are not as obvious as they may seem. Mug shots did not come into regular use until the late 1880s (almost fifty years after the invention of photography), their utility having first been demonstrated by a French clerk, Alphonse Bertillon, in the capture and punishment (execution) of participants in the failed Paris Commune of 1871.

In fact, the first documented uses of criminal photography arose from the nineteenth century desire "to prove the existence of innate, visible traits in deviants, or to serve as a dispassionate document of their deeds." On the heels of Darwin's theories of human origins arose many theories attempting to link behavior to physical characteristics. In the age of such cutting-edge sciences as phrenology, photography was the perfect documentary medium of the tell-tale physical appearances of the socially aberrant. One such fascinatingly misguided study exhibited here was conducted by a French physician named Guillaume-Benjamin Duchenne (Duchenne de Boulogne). In attempting to prove that facial expressions are universal rather than individual, Duchenne applied electric shocks to his subjects' faces, photographically documenting the resulting expressions.

By the beginning of the twentieth century, crime photography had become a standard form of evidence—a means of identifying individual criminals, rather than criminal types, and of documenting and recreating crime scenes. That is not to say that its uses were any less manipulative. Carol Squiers, in her essay, "And So the Moving Trigger Finger Writes," parallels the rise of the American tabloid newspaper with the popularity of crime-scene photography. As many of the photos in the exhibit demonstrate, photographs of captured criminals—dead or alive, though preferably dead and perforated with bullet holes—fascinated readers and helped police to simultaneously vilify criminals and gangsters and to glorify their own efforts. The purulent images of slain 1930s gangsters (in particular, a shot of a mortally wounded Dutch Schultz raising his head off a hospital gurney to examine his bullet-riddled torso) render today's tabloid portrayals of criminal violence almost squeamishly respectful.

Though the majority of the photographs in this collection are American, some of the most haunting and sad images are from two projects conducted by other regimes: the Khmer Rouge and the French occupation of Algeria. In the mid-1970s Nhem Ein, a Cambodian teenager with some photographic training, and five assistants photographed prisoners in the Phnom Penh interrogation/torture center, Tuol Sleng, before they were summarily executed in the Choeung Ek killing field. In the early 1960s, as the French army attempted to put down the revolution in Algeria, they attempted to document natives with identification cards. To this end a young French soldier, Marc Garanger, photographed almost 2,000 Algerians, primarily women with their traditional veils removed. These photographs, in their unflinching documentary honesty, demonstrate, better than any of the others in the collection, the almost violent intrusiveness of the lens on its captive subjects. These photographs so belie the intended implication of criminality that the most obvious message is the futility of the propagandistic attempt. Their inclusion, though seemingly nominal, documents what is at the heart of this collection: photography may be used to bolster lies, but the photos themselves cannot.

Rain Taxi Print Edition, Vol.3 No. 1, Spring (#9) | © Rain Taxi, Inc. 1998