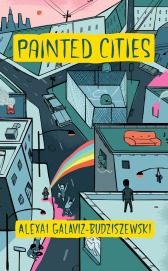

Alexai Galaviz-Budziszewski

Alexai Galaviz-Budziszewski

McSweeney’s ($24)

by Scott F. Parker

The short stories of Alexai Galaviz-Budziszewski’s Painted Cities are set less in the Pilsen neighborhood of Chicago than in the personalized dreamscape adapted from that place by the narrator, Jesse, who serves as a cipher for his environment. In the story “Sacrifice,” about Jesse’s struggles with his wife’s son’s birth father, he says, “But none of this explains who I am. And truth is I am no one.” Most of what we learn about Jesse we learn by what he witnesses in adolescence and now preserves, though much of it is brutal.

Pilsen—arguably the book’s main character—is marked by poverty and violence, gangs and urban blight. It is the kind of place where gunfire erupts at a cotillion, kids pan for gold in fire hydrant water and hide on the roofs of abandoned factories, and a man orders beers after being shot while he waits for the ambulance. Yet the stories recall such incidents with a fondness for those moments of beauty that were sought if not always found, and an optimism that some of the neighborhood’s denizens might rise up from their circumstances. One character, “even though he had been shot the moment he . . . yelled ‘Truce,’ he had made a completely heartfelt attempt at doing something in his life.”

Story after story explores the theme of reality/unreality as the world is distorted through the prism of memory. “My memories compete with reality,” Jesse reports in the opening story, “Daydreams.” Or later in the same story: “all I can recall is what it felt like. I try to piece together image from that.” Despite such preoccupations with the real, the book’s mood is anything but ponderous. The stories are written in a compressed style heavy on vivid scene; a powerful intimacy emerges from the specificity of detail and idiosyncratic logic of Jesse’s private world, through which Galaviz-Budziszewski’s love of the neighborhood becomes apparent.

In the story “God’s Country” we get a sense of why this matters so much when we read about Chuey, a neighborhood boy who develops the ability to raise animals (including humans) from the dead, a skill he claims to have acquired in “Sonora, God’s Country.” Looking back on this period from the vantage point of adulthood, Jesse says,

I still think about raising the dead, every day. Sometimes, in my bathroom, I will find things, a dead spider, a dead ladybug, or, every so often, a cockroach. And just for fun I will close my eyes, open them, and touch the dead body. I’ll hope that my finger will give life, that I’ll feel again what I felt when I was fourteen, when, in this whole damn neighborhood, among all this concrete, all these apartment buildings, church steeples, and smoke stacks, we were somebody.

This is not the kind of book to which the reader complains, “Am I really supposed to believe that a boy from Chicago can raise the dead?” Not when the book itself does just that.