Ricky Jay

Siglio Press ($39.95)

by Jeff Alford

See Gallants, wonder and behold

This German, of imperfect Mold.

No Feet, no Leggs, no Thighs, no Hands

Yet all that Art can do commands.

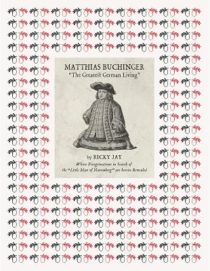

This is the first quatrain of a poem celebrating the life of Matthias Buchinger, who, born in 1674, lived to be an accomplished magician, micro-calligrapher, and musician despite his lack of limbs and an adult height of twenty-nine inches. In Matthias Buchinger: “The Greatest German Living”, esteemed collector and magician Ricky Jay chronicles his obsession with the Little Man of Nuremberg, illustrated profusely with ornamental and wildly detailed micrographic works by Buchinger that have since found their way to Jay’s private archives.

This is the first quatrain of a poem celebrating the life of Matthias Buchinger, who, born in 1674, lived to be an accomplished magician, micro-calligrapher, and musician despite his lack of limbs and an adult height of twenty-nine inches. In Matthias Buchinger: “The Greatest German Living”, esteemed collector and magician Ricky Jay chronicles his obsession with the Little Man of Nuremberg, illustrated profusely with ornamental and wildly detailed micrographic works by Buchinger that have since found their way to Jay’s private archives.

Jay maintains a respectful distance from anything exploitative: the “how” of Buchinger (“a joynt . . . at the elbow, with a bone about an inch long & a thick muscle about two Inches long”) is glossed over on the way towards the more celebratory “who”: this was a man not who only overcame his disabilities but a performer who revolutionized self-promotion and advertising. His routine, consisting of feats like threading a needle, showcasing his calligraphy (rendered in both upside-down-, micro- and mirror-script), cup-and-ball legerdemain, and performances on unique instruments of his own creation, traveled throughout Europe and garnered significant notoriety. Souvenir etchings, featuring the various states of his performance, were sold and lavishly inscribed by Buchinger, “born without feet or hands” (an epithet he was wont to include with his signature).

Ricky Jay is not at fault for what occasionally feels like a shallow biography: there’s a dearth of information on Buchinger and Jay has done a commendable feat in his synthesis of the little material available. He bridges the lacunae in Buchinger’s history with educated, well-researched conjecture, and he uses these ideas with the few written sources he's found to shape a remarkably realized life.

Buchinger was culturally nimble: Matthew Buchinger in England, Matthieu Bouchingre in France, he was well-versed in the languages of the continent and maintained an entrepreneur’s confidence regardless of his realm. Jay unearths letters between Buchinger and various benefactors, and the little correspondence available provides some insight into his personality. He was a businessman capable of kindness and levity, and a family man, too. Buchinger’s breathtaking family tree (composed of two mesmerizing sheets, reprinted here with cut-outs) outlines, with curling flourishes, the birth of his fourteen children to four wives over twenty-five years.

One of Buchinger's most famous works is a self portrait in a luxurious powdered wig. Upon closer inspection, one can see that the waves of Buchinger's wig are composed of text: seven complete psalms and the Lord’s Prayer roil through the man’s coif. In later pieces, one can just barely make out the Ten Commandments and Apostle’s Creed integrated into some architectural details of an interior drawing. These tenets are not just impressive in their craft but compelling in their content: To discover the words, “I Blieve in God the Father Almighty, Maker of Heaven and Earth” and to think of the hand (or lack thereof) that penned them warrants a profound moment of reflection. One can interpret Buchinger's piety as trusting God’s will, or, alternatively, meticulously seeking affirmation that his corporeal fate is part of some grand design.

Reading Matthias Buchinger: “The Greatest German Living” feels at times like being pulled around a collector’s library by its frenzied curator. But perhaps that “The Greatest German Living” is more about its investigation than it is about its subject is the true goal of the text. Tangents abound as Jay recounts stories of other collectors and magicians: names are dropped with little resonance, and, a lengthy digression later, finally circle back to Buchinger. The book includes a slew of bibliographic sources in the back matter, but also features floating, numberless footnotes in many of the margins, disconnected from any particular passage. When a paragraph, bordered by this marginalia, cites a drawing reprinted elsewhere in the book and mentions an “important relationship” upon whom Jay will elaborate later in the volume, it’s hard to know which way is up. Like Buchinger’s micrographic wig, we’re left to swirl among the details.