Edited by Laura Kuhn

John Cage Trust ($24.95)

by Richard Kostelanetz

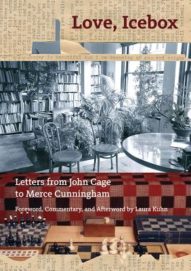

More than a quarter century after his death, the American composer John Cage (1912-1992) is still remembered as fresh editions of his work continue to appear. A handsomely produced book, Love, Icebox consists of unashamedly personal letters that Cage posted to his future life partner, the choreographer Merce Cunningham (1919-2009), in the early 1940s; these were discovered among the latter’s papers after his death.

More than a quarter century after his death, the American composer John Cage (1912-1992) is still remembered as fresh editions of his work continue to appear. A handsomely produced book, Love, Icebox consists of unashamedly personal letters that Cage posted to his future life partner, the choreographer Merce Cunningham (1919-2009), in the early 1940s; these were discovered among the latter’s papers after his death.

Though the letters are slight—rarely more than a few hundred words—they richly portray a man “happily married” to a woman in the process of discovering his greater love for another man. Additionally, they reveal how gay young men approached each other several decades ago. Remarkably few mention aesthetic matters or experiences, though we later came to treasure both of these artists for the work they made together and through each other. Some are shamelessly erotic, to a degree that would have probably made them unpublishable only a few decades ago. What’s missing are Cunningham’s replies, though Cage saved things; one suspects that Cunningham insisted they be destroyed.

Because the texts are so slight, the book benefits from the addition of reproductions of the original letters, often handwritten, and color photographs of the Cage-Cunningham loft soon after the latter’s passing. As Cage’s principal executor, Laura Kuhn adds extended footnotes that are informative though sometimes wrong. (E.E. Cummings’ signature shows that he spelled his name with initial capital letters; John Lennon and Yoko Ono resided in the early 1970s not in the same building on Bank Street as Cunningham and Cage, but in an adjacent building.)

Other themes of this book include Cage’s loneliness and insecurity in cultivating a lover who was always traveling elsewhere, not only performing but teaching, teaching, and more teaching. This distance prompts Cage to question sometimes whether his distant lover is equally loving. If only through mentioning his recent reading, Cage reveals how much he was influenced by books that weren’t necessarily about music. By mentioning prominent New Yorkers that he met during his first two years there, Cage also demonstrates his skill at meeting and impressing his elders, even if they often deprecated his radical artistic ideas.

The appearance of this volume prompts mention of a fuller volume of Cage letters that appeared in 2016 from Wesleyan University Press, which had been his principal book publisher since 1961. Most of these are also remarkably slight, even when addressed to people with whom he worked, as Cage functioned at a high level of trust. Still, what is here is illuminating; hopefully we can expect the John Cage Trust to produce more fresh books, each as surprising and valuable as this.