and Other Poems

and Other Poems

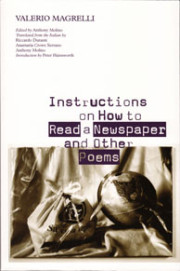

Valerio Magrelli

translated by Ricardo Duranti, Anthony Molino,

and Anamaria Crowe Serrano

Chelsea Editions ($20)

by Kevin Carollo

The poem is what lies between a between.

—Mahmoud Darwish

With a blurb pedigree that includes the late Octavio Paz, the late Joseph Brodsky, and Jonathan Galassi (thankfully alive and translator of the late Eugenio Montale and Giacomo Leopardi), this fantastic collection of Valerio Magrelli’s poetry is good news indeed, and instructive in many ways. Its appearance provokes myriad questions about the contemporary dynamics of Italian poetry, Italy’s place in world poetry, the archeology of identity in the era of globalization, the role of poetry in daily life, and the mysterious alchemy of language that we use to remake ourselves. Magrelli writes deep, contemplative stuff, but his poems are more heady and heavy than heavy-handed. One of the most curious lessons to be gleaned here involves the elusive vanishing point of incredible poets in the world—poets writing in so many different languages, and who seem to randomly surface here and there, or not, perhaps well known in their county of origin, or read solely by a handful of people in the know. They may become appreciated posthumously, lapse into obscurity “prehumously,” or turn up in one of the many contemporary anthologies and journals of world poetry coming out these days. Though publishers in the English-speaking world have started to wake up to the vitality of those all-too-foreign languages and writers, the majority of great work will never reach their intended audience—you, of course. Clearly, the Nobel Prize can only do so much for the world’s obscure poets. So who is this guy?

Born in 1957 and first published in his early twenties, Magrelli has become more fascinating with each successive collection. This edition of Instructions on How to Read a Newspaper includes Anthony Molino’s selected translations from the 1980s (originally published by Graywolf Press in 1991), and culminates in the title track book, originally published in 1999. It’s important to note that Magrelli translates from French, and his concerns with the quotidian nature of identity in an age of newspapers bring to mind those of Stéphane Mallarmé over a century ago. Now that newspapers are heading for a kind of vanishing point of their own, it seems crucial to do some digging into the metaphysics of our daily disappearing acts.

A Magrelli poem is a quiet bite, pitched somewhere between the American poetics of the late Robert Creeley and Poet Laureate Kay Ryan. See “Date,” the opening poem of Instructions:

This is where it starts

with the light of a dead star

arriving from a past present perfect.

Its today is a yesterday, a corpse-light,

the memory of some daily afterlife.

The present serves as an inevitable beginning from which Magrelli insinuates the cyclical, thanatological grammar that we ritually employ in our daily lives. Like newspapers, we are composed of what has already come and gone—the present as simultaneous decomposition and re-composition.

The poems here are deftly translated, but cannot incorporate all the nuances implicit in Magrelli’s Italian. For example, the opening line, “Si comincia da qua,” can also mean “One starts from here” or “We start from here”—all possibilities that further blur our fates with that of our dailies. For translators of Spanish and Italian especially, languages in which most locutions have a given sonority and ready rhythm and rhyme, the literal meaning of a poem functions as a sort of raft from which they cast for greater and more polyvalent fish. Magrelli knows what translators are wrestling with when he writes this short, untitled poem from Nearsights:

We stand on the wharf

as if on a ruin,

a bridge

onto the sea.

Whether written by Wang Wei, Antonio Machado, or Giuseppe Ungaretti, short poems typically strive to induce that inarticulate “a ha!” sensation, the intense and evanescent play with the “corpse-light” of today. The fact that Magrelli’s poetry in English resonates more often than not testifies to the talent of the volume’s three translators. And because Magrelli remains intensely interested in the geology and architecture of language throughout his work, each poem also serves as a meta-commentary on the natural and unnatural processes of bringing language into being.

This is heavy stuff, to be sure, but Magrelli makes this kind of uneasy inhabitation look easy, as can be seen in “Medicine: Voice Transplant”:

Apart from his accent, the patient is already talking

like his donor, still

no metempsychosis or ventriloquism. The only thing is,

his wind tunnel has shifted

and the new owner has begun to test

the aerodynamics of the old Logos.

In this series, Magrelli includes “medical” verse on cloning, cryogenesis, as well as “Bits of DNA from Fireflies grafted onto Strawberries,” all poems that offer eerie ruminations on the simulated nature of contemporary life. The poem “Medicine: Dolly’s Eye” concludes by gazing at the original copy of a sheep:

Look at the way her double inhabits her

and leaks through her stare. It is there

like a mirage, a lookalike, a vicarious body,

a shadow that appears to be waiting for someone

to return.

The lost passerby

at the crossroads of the breed.

Here, translators Duranti and Serrano artfully and successfully play with line breaks and word choice to maintain the tension of the original. This bilingual edition comes with an editor’s note, an introduction, and an afterword, all sensitive to the crossroads of translation where Magrelli’s poetry resides—a delightful crossroads that lies between the between of the very stuff of us. Instructions is the where where we should start.