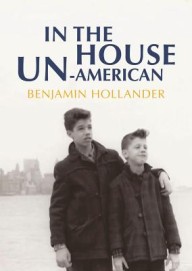

Benjamin Hollander

Benjamin Hollander

Clockroot Books ($15)

by Michael Wendt

Early in Benjamin Hollander’s In the House Un-American, the question is posed: “if everyone is truly welcome [in the United States], why does there exist, in phrase and condition, the un-American?” Throughout the course of the rest of the book we follow Carlos ben Carlos Rossman, a Puerto-Rican Jew with roots in the Middle East, through a protean Bildungsroman that unfolds, by turns, through direct narration, philosophical meditation, brief letters, and transcripts from the House Un-American Activities Committee hearings. Rossman and the characters he encounters take it upon themselves to examine the American narrative that prizes both difference and inclusivity in name while never truly embracing either in substance.

Part and parcel of this exploration is the supreme lack of difference characterizing American language use. Rossman is said to recall that he expected the vocabulary of Americans “like the people to move, to change and expand as it moved, but it only diminished.” And so, by contrast, language that moves, changes, and expands becomes cast as un-American. The fundamental irony, then, is that un-American literature holds the potential to realize the pluralistic promise central to the American fable, as well as the poetic “field of action,” articulated by Rossman’s namesake William Carlos Williams, in which categories of prosody and literary structure are never fixed or discrete.

In the House Un-American situates itself within a body of literature—one inhabited by Williams, Kafka, and Melville, among others alluded to in the book—that is charged with the representation of narrativized thought unfolding. Special attention is paid to exploring the “truths” of the American mythos: “self-evident and, as such, beyond reason and divinely informed,” these “truths” are measured against a constellated set of narratives circumscribing the myriad national, religious, and ethnic identities of the book’s characters. And it turns out that these narratives aren’t so different; that “one country could become fabled depending on how it used the facts of another;” that “the Heart of Islam is American.”

But that last statement may be a bit too declarative to be representative of Hollander’s ambulatory and philosophically charged prose, which continuously expands and moves per Rossman’s expectations. As such, Hollander’s writing seems decidedly “un-American,” like the writing of an “un-person” set to “take its revenge and flow through the [world of American letters] like flood-water”—or, to borrow from William Carlos Williams, Hollander’s writing exists in a “field of purposive action” constantly seeking “new means for expanded possibilities in literary expression.” However one chooses to articulate the experiments Hollander undertakes, what remains clear is that such experimentation, in Hollander’s hands, never removes the ideas from an immediate relationship with the world.

And therein lies the import of the formal ingenuity of In the House Un-American: it is experimentation in the service of a deeper conversation with the world, an unmooring of language from ideology and idolatry. In being un-American, Hollander’s writing seeks an English that is “accented or a bit cracked in its fluency . . . to not only discover ‘the wound in every word in the effort to democratize language,’ but to uncover the world in the wound exposed.”