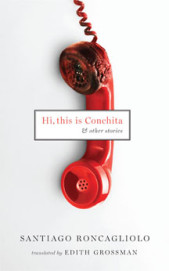

Santiago Roncagliolo

Santiago Roncagliolo

translated by Edith Grossman

Two Lines Press ($17.95)

by Jenn Mar

Santiago Roncagliolo's latest story collection is a black comedy that exposes the incongruities of modern life. For the Peruvian author who was listed as Granta's "Best Young Spanish-Language Novelist," no subject is too profane. His stories follow some of literature's most perversely-misguided crackpots as they attempt to find human connections in shamelessly-obscene acts: an office drone engages in phone-sex involving coffee-machine burns and metal-pointed leather whips; a medical examiner intimately touches the insides of a cadaver's body.

Readers can bound through the book in a single evening, as the collection consists of an ungainly novella ("Hi, This is Conchita"), and three other stories of a broad stylistic range. The title piece is a smorgasbord of sex and violence: it follows the intertwining lives of a phone-sex operator and the client who loves her, a husband who hires a hit man to kill his mistress, and a serial drunk-dialer. Heavy portions of phone sex, pornography ("The actor playing Clarke Gable is sticking it in the mouth of one of the Confederate widows. It's to comfort her, I think"), and bathtub dismemberment all play out against the banal backdrop of billing statements and Meg Ryan jokes. Written entirely in dialogue, the story uses the gimmick of telephone conversations to plot out events, but readers may come to feel irritated by the task of checking the twisting plotlines against the telephone numbers that are displayed at the heading of every chapter in the absence of exposition.

In contrast to the speedy "Hi, This is Conchita," "Despoiler" keeps a measured pace, and is built on masterful sentences of architectural symmetry and echoing salience. It follows Carmen as she celebrates her fortieth birthday with her coworkers at Carnival. The nightmarish evening soon conjures the oversized beast that is her repellent childhood. The surrealism of costumed partygoers, dressed as wolves and skeletons, blends with Carmen's flashbacks as her internal landscape distorts the dimensions of her real life.

"Butterflies Fastened with Pins," about a man recalling the names of friends who keep killing themselves, is Roncagliolo's appropriation of the poetic tradition of litany. Meanwhile, "The Passenger Beside You" prompts absurdist comedy to consider the metaphysics of the human lifespan. This story is told by a young woman who speaks from the afterlife about the gunshot wound in her chest. After recounting the violence of her last hours, she describes the splendor that she is shown at the mortuary by a handsome doctor, who slides his hands inside her body in the ritual examination of the corpse, intimately touching her insides. The story is as breathtaking as it is grotesque.

Good comedy contains an equal measure of well-timed repetition and surprise, and Roncagliolo succeeds most when his comedy is agile enough to accommodate for tenderness as well as tragedy. In this collection, our lives assume the shape of a joke. The joke, of course, is that we've responded to our estrangement by seeking overblown fantasies, algorithm-inspired services, and flimsy machines to impersonate the impact of real human connections.