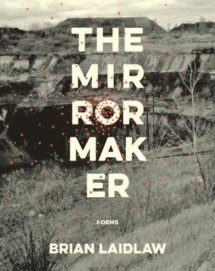

In November 2019, I sat down with Brian Laidlaw, a poet and songwriter, at a coffee shop in Red Wing, Minnesota. Joining our conversation was Molly Sutton Kiefer, who like Brian received an MFA in Poetry from the University of Minnesota. Though he has since moved on from the state, Brian was in town for a songwriting workshop he was asked to lead later that day; within a dusty corner of a beautiful old barn, Brian talked about his personal experiences, gave songwriting tips, and performed a beautiful rendition of “Dark Sides,” which has a companion poem by the same name. In discussing the difference between song lyrics and poetry, he told us poetry is generally being more “compressed” while songs are usually more “generous.” Later that night at the famed Anderson Center, Brian, accompanied by his partner Ashley, performed poetry from his two collections published by Milkweed Editions, The Stuntman (2015) and The Mirrormaker (2019), along with songs from their companion albums.

Owen Schauss: How did your creative life begin?

Brian Laidlaw: I went into this one kind of sideways. I started out being much more committed to music, and learned guitar from my mom in middle school. Then several of my friends started playing guitar at about the same time. We were teaching each other how to play these chords. I continued being a lead electric guitar player up through middle school, high school, and into college, and it wasn't until midway through college that I started playing the guitar in a blues band, where the main songwriter was more of an acoustic/fingerstyle/open tuning/really elaborate guitar-playing songwriter. That was the point where I started playing acoustic guitar more and began doing some tentative songwriting.

I was also taking poetry classes and treating them as something very separate from the songwriting, and that was the point where I started adapting poems I had written for the page into song lyrics by making them rhyme and finding lines to repeat as a chorus. I first started playing shows with my own music in college.

OS: So it started as your poems turning into lyrics. Do you still write like that?

BL: I did for a while and I don't anymore. At first I really struggled to know the difference between poems and songs, so I would have an impulse. A lot of what I was writing poetry-wise was metrical and rhyming and was in regular forms, so it translated more readily into song lyrics because they were following the same rules. As time went on the two practices diverged. I still have a soft spot for tweaky meter and intricate rhyme schemes, but now that's all in the songwriting. When I write poems, I write pretty weird poems; they don’t rhyme, they have very little regularity whatsoever. They wouldn't be well-suited to try to sing, but the way that I’m doing it now, with the last couple of projects I released with Milkweed, is writing books of weird poems that come with a companion album. The music is like a soundtrack to the book.

BL: I did for a while and I don't anymore. At first I really struggled to know the difference between poems and songs, so I would have an impulse. A lot of what I was writing poetry-wise was metrical and rhyming and was in regular forms, so it translated more readily into song lyrics because they were following the same rules. As time went on the two practices diverged. I still have a soft spot for tweaky meter and intricate rhyme schemes, but now that's all in the songwriting. When I write poems, I write pretty weird poems; they don’t rhyme, they have very little regularity whatsoever. They wouldn't be well-suited to try to sing, but the way that I’m doing it now, with the last couple of projects I released with Milkweed, is writing books of weird poems that come with a companion album. The music is like a soundtrack to the book.

OS: So your poetry shifted into songwriting, leaving you with a new style of poetry?

BL: That’s a really good way to put it. I think it was just because of what I was reading. During my time at the U of M, in particular, I was reading much stranger poets and getting into more fragmentary, experimental forms of writing, and I felt like that's what I wanted my poetry to do. Fortunately I had this more user-friendly way of writing that continued to happen in the songwriting. I think I have always been aware of how fragmentary, elliptical, weird, experimental poetry can be pretty alienating to most readers. So that's the trade-off, but music can still fill that space.

Molly Sutton Kiefer: I remember you came into the program with very narrative lyrical poems, and then at the end the white space became another big tool for you.

BL: For sure, I think it was a big coming-of-age process. Those earlier poems feel so different to me. I think all of that stuff has found its way back into songwriting.

OS: Since your songwriting is different from your poetry, are there different inspirations for them?

BL: Very much so. I think the most broad way to put it is that the poems are coming from my brain and the songs are coming from my heart. When I feel the big tug on the heartstrings—whether it’s because of a place I'm in or a person that I'm with or a situation that I'm facing—I often turn to the guitar; it feels more immediate. Conversely, I'm writing poems to work through things, and I’m currently in conversation with a lot of environmental literature, talking about the intricacies of the way that ecosystems are in balance and falling out of balance. It’s so dense that it doesn't translate nicely into a song; it has to be something that’s more finely wrought. But within that, I go through long periods where I'll only be writing songs; it's not uncommon for me to go a year or two without writing a poem at all. Conversely, there are stretches where I'm writing tons of poems. Right now I'm writing almost entirely essays and not writing songs very much unless there's commissioned work or stuff that's happening in more focused, project-oriented way.

OS: So you don't feel pressured to produce more books or music for your audience?

BL: I feel pressured to be producing something, but I don't think that I feel the pressure any more for it to be in a particular shape.

OS: And your essays take the place of your poems and music?

BL: Right. I know how to write a good song and what the songwriting process will be like; every time is different but the process I go through to write is similar. I've been teaching it forever, I’ve been practicing it forever. Even for poems, to a certain extent, I know the kind of magic that happens while you're writing. So it's been really fun writing these essays because it's actually a form that I don't know, so every time I'm writing, it’s this radical process of discovery again. It's been rewarding to be doing something new and having the form itself be revelatory.

OS: These processes are very detailed. Is there a specific writing time that suits you?

BL: When I'm in poem-writing mode, I can always bang out a poem in twenty minutes either late at night right before bed or even in between things. It's a really rapid flash with poems. With songs, I find that the best songs require at least an hour or two of uninterrupted time so that I can start putting all the pieces together. My favorite song writing processes are the ones where I have all night—having six or eight hours to do the whole thing top to bottom. The challenge is my life at this point is really fun but I’m on the road and doing all different kinds of things, so it’s rare that I have those really long stretches of uninterrupted time. That's something I'm still trying to navigate: How can I get a start on a song with twenty minutes and then return to it? I rarely do.

OS: With songwriting, were you always interested in the lyricism?

BL: It was really not until college that I started listening to music where the lyrics were an important part of what was happening. I’d say the key record for that was In the Aeroplane Over the Sea by Neutral Milk Hotel; I realized, “Oh, wow, this record wouldn't be what it is if it weren't for what the text is doing.” It was such a basic revelation, but a really important one. After that I started seeking out more music that was more lyrics forward. In terms of contemporary stuff, The Decemberists were a big influence, Joanna Newsom, some Iron & Wine, Regina Spektor—all the stuff that's contemporary using story-based song lyrics. Working backwards from there, I got very deep into Bob Dylan and Leonard Cohen and Nick Cave and Shane MacGowan.

OS: When you write music, do you usually come up with the lyrics first and then the chords, or is it the other way around?

BL: Much to my detriment, I write the lyrics first. In the time of my teaching at McNally Smith I realized I’m the only person who does that—all of my students write the melody simultaneously with their text, or they write the guitar parts and then fit text to it after—but in my case, I almost always write without my guitar. I’ll write a set of lyrics, but then because I am such a tweaker about meter and rhyme, I already know that they're going to be perfectly regular. I know that as soon as I pick up an instrument, I'll be able to sing it because all of the words will land where they're supposed to. The trade-off is that I don't write particularly adventurous melodies because the texts are already in place and I'm just delivering the text instead of having the melody inform the text as I'm writing it.

OS: I've heard people say that song writing and writing poetry are very hard professions to make a living in. What has been your experience in this field?

BL: I’m so glad you asked that question. Honestly, I feel very prosperous right now. I'm in a really good place and I think that a lot of the folks in my age bracket and place in their careers are too. I don't think that it's impossible or even necessarily that difficult. The challenge is that there's not a prescribed template for how to do it. In many professions if you want to make money doing X, you do these seven steps, but there's not that same kind of path for writers. The flip side is that when we're approaching our own creative work, we are drawing on the full capacity of our minds to think around problems and to come up with unexpected solutions to the challenges that we’re facing in the context of a tune or a poem. Very often when artists try to make a living, they stop being creative. All the creativity goes away and they're just like, “Well, I'm supposed to do a Master’s and then I'm supposed to do this and this and then I'm supposed to submit to this thing and then this is supposed to happen.” My response to that is, “Wow, that's so uncreative!” For me, what’s really uncreative is being in a band and putting out a record, just as a basic approach. That's kind of boring, it's an outdated thing to do, but people still do it. And then they’re thinking, “Well, now we're supposed to tour and we're going to do it this exact way.” It's really difficult to make a living doing all the regular things that you're supposed to do. But if you access your creativity about how you actually approach your career, in addition to being creative about the work that you're producing, I think it becomes both really doable and really fun to invent a career for yourself.

BL: I’m so glad you asked that question. Honestly, I feel very prosperous right now. I'm in a really good place and I think that a lot of the folks in my age bracket and place in their careers are too. I don't think that it's impossible or even necessarily that difficult. The challenge is that there's not a prescribed template for how to do it. In many professions if you want to make money doing X, you do these seven steps, but there's not that same kind of path for writers. The flip side is that when we're approaching our own creative work, we are drawing on the full capacity of our minds to think around problems and to come up with unexpected solutions to the challenges that we’re facing in the context of a tune or a poem. Very often when artists try to make a living, they stop being creative. All the creativity goes away and they're just like, “Well, I'm supposed to do a Master’s and then I'm supposed to do this and this and then I'm supposed to submit to this thing and then this is supposed to happen.” My response to that is, “Wow, that's so uncreative!” For me, what’s really uncreative is being in a band and putting out a record, just as a basic approach. That's kind of boring, it's an outdated thing to do, but people still do it. And then they’re thinking, “Well, now we're supposed to tour and we're going to do it this exact way.” It's really difficult to make a living doing all the regular things that you're supposed to do. But if you access your creativity about how you actually approach your career, in addition to being creative about the work that you're producing, I think it becomes both really doable and really fun to invent a career for yourself.

In my case, I think a large part of why I've had success getting books published has been because of combining it with the music. There’s not that many other people doing it. It also means that I get to go to literary festivals, and it allows me to do things like what I’m doing here, be the one person who is talking about poetry and songwriting at what’s otherwise just a poetry series. Finding this weird career that is not being done by many other people, I think of it as a meta-creativity—being creative about your career in addition to being creative about the material produces an artist.

There’s a company I work with that does poetry and songwriting mentorship for people with autism, which is another thing that nobody else is doing. It's such powerful work and totally unexpected. That's some of the work that I'm most proud of, and it’s also something that there was no prescribed path to have arrived at. Instead, it came about by cultivating an openness to those opportunities and recognizing what your strengths are and understanding how to use them in a way that serves people. As long as you're flexible about that, I think that there's always a way to make a living as an artist, especially if you're disciplined about it.

OS: What advice would you give to someone who's interested in pursuing the songwriting and poetry field?

BL: Being willing to treat it like a job, and recognizing that for most people, they probably love (if they're lucky) only 50% of their job. I might venture a guess that certain teachers among us might really love being up in front of the class and find it really rewarding to do lesson planning. You probably don't love grading, for example, seven stacks of essays every day. The point is there's always a percentage of work that’s a drag, even in a dream job. I find that to be the case for being a writer. I love revisions. I love the creative part. I love doing public engagements. I don't love submissions. I don't love getting handed down edits from an editor, but that's something that does happen. Book promotion is something that I've had to wrap my mind around. This is just to say if you approach your artistic career thinking, “I'm going to love every second of this,” it’s not going to work. You have to go into it knowing that there's going to be parts of it that are a drag, but also to remember, “I bet 20% of what I do is a drag,” as opposed to a higher percentage. And the other part is what I said before: Being creative in the way that you approach it. Trying to think around the challenges. I'm thinking about a band that's having a hard time booking a show at the club in town. Instead of saying “Okay, I guess we can't do it,” say, “No, we can do a house concert or a free show in the park." Being creative is how you end up in exactly the right place. It has always been my dream to be doing exactly what I'm doing today—poetry slash songwriter events in a literary context—and now I'm getting to do it. Having clarity about what it is that you want is extremely important. I think a lot of people are thinking “I want to succeed as a writer,” but there's no way to work backwards; you need to establish credentials and it can be a grind. The artists I know who work really hard, they make it work. The core of it is a dream. You’re doing the exact thing that you want every day. That's good. That's rare.

OS: That's really inspiring. Knowing that if you have your dream in mind, you can work your hardest and achieve it.

BL: Oh, definitely. The most important lesson is that to decide on an artistic career is not to take a vow of poverty; if you are disciplined about it, it'll work, you'll figure out a way. It’s not eating rice and beans and living in the basement forever. You can have a good life and be comfortable and also immensely happy.