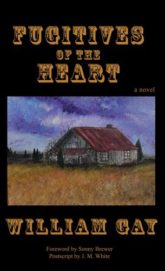

William Gay

William Gay

Livingston Press ($28.95)

by Chris Via

When he died in early 2012, William Gay left behind an attic full of unpublished writing in his Tennessee home. Thankfully, a group of friends culled several novels from this bounty, the last of which is Fugitives of the Heart. Gay’s previous novels—among them The Long Home (MacAdam/Cage, 1999) and Provinces of Night (Doubleday, 2000)—and his numerous short stories situated him most definitively in the Southern Gothic tradition. This final posthumous novel continues to bear the marks of influence from William Faulkner, Flannery O’Connor, and even Cormac McCarthy (with whom Gay enjoyed correspondence), but its most overt homage is to Mark Twain—specifically Huckleberry Finn—painting a darker, more violent Twain than the folksy image we so often associate.

Gay is far from derivative. He spent most of his life perfecting his style, not seeing publication until age fifty-nine. As editor J. M. White says in his postscript: “By the time he got published . . . he had been writing for over thirty years . . . At age twelve, he got a notebook and sharpened a stick and made his own ink out of walnut stain and started writing.” This romantic image of the determined young neophyte also reveals the milieu in which Gay lived all his life: working-class mining towns in the “High Forest” of Lewis County. There, Gay developed his craft outside the classroom and without the assistance of writing circles, so it is a testament to an innate and uncanny ability to spin yarns and adorn sentences that Gay achieved the level of artistry, command of language, and sense of characterization that he did.

Fugitives of the Heart begins with an unforgettable sentence: “Yates’s father’s sole claim to immortality was that he used to cause good car wrecks.” From there unfolds the story of a young boy whose peregrinations and adventures (or misadventures) we follow through the ridges and glens of backwoods Tennessee. This is a place where people are so poor they do not “even possess a shovel to bury the dead”; where if “all you had to sell was the labor of your own body you clustered with these gaunteyed men clutching their lunchbuckets waiting for the work whistle to blow”; where people feel they are “in the waiting room of hell just listening for someone to open the door and call out my name.” Bereft of any person or place to which he can anchor his heart, on the run in the woods, and on the cusp of his “coming of age,” the young, vigorous, and intrepid Yates seems attracted to conflict, prone to accident, and immune to consequence. But his string of capers and narrow evasions are catching up with him.

Gay also shines as a master of atmosphere. From Homeric descriptors like “inkblack sea,” “rainwet stone,” and “whippoorwill dark,” to such Joycean compounds as “sunrimpled” and “dreammist,” to mot juste adjectives like “spurling” and “moiled,” the prose plays a poetic mimesis to the setting. The oppressive Tennessee heat is palpable in passages like “The boy’s face looked flat and unfriendly in the white weight of the sun,” and we find ourselves plunged into Yates’s world through dialect (“It just don’t sound like the way Bible folks ort to talk”) and natural descriptions that assault the senses: “He went under tendrils of honeysuckle and bright orange bells of cow itch through a steady droning of bees into a deep cloistered coolness with a damp reek of peppermint.”

By the end of this gripping novel, the final line amends the suggested immortality and humor of the opening one: “Nothing but the earth endures.” Yet the ephemerality of humanity and its various milieux across history are not without beauty, as the two paragraphs preceding the closing words exemplify in a sweep of prose that perfectly caps this hard-hitting volume. If potential readers are wondering whether there is still newness in the tales of hard-scrabble Southerners, William Gay’s final work in an impressive oeuvre offers a veritable rejoinder with this, a novel that no doubt will leave them gutted and altered.