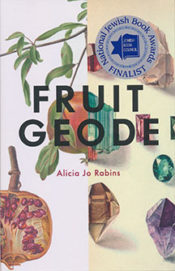

Alicia Jo Rabins

Alicia Jo Rabins

Augury Books ($16)

by Anat Hinkis

The experiences of childbirth and early motherhood are simultaneously physical and metaphorical in Alicia Jo Rabins’ new collection, Fruit Geode, which was selected as finalist for the National Jewish Book Award in 2018. In resonance with Rabins’ first collection, Divinity School, there is a strong sense of the physicality in the human experience, though the spiritual constantly hovers within reach. The collection opens with the poem “Beautiful Virus,” where the irrepressible power of nature, entwining life and death, culminates in the sweet yet terrifying magic of early parenthood:

Like arsenic in chocolate

Like a pea shoot in mud

You broke me open

Into death-in-life

A beautiful virus

Uncontrollably growing

As the morning glories

Climb the raspberries

That choke the grapes that

Overrun the spinach

What I mean to say is

Knocked off the pedestal

Of wholeness

Now I watch you breathe

In your miniature

Flamingo pajamas

This loss of “wholeness,” a breaking open, is the main trope around which most of the poems revolve. As the feminine body opens like a ripe fruit to give life, then lends itself to nourish and nurture the baby’s needs, the sense of self is altered, sometimes beyond recognition. The fruit geode of the book’s title (a splitting in half of a fruit rather than a crystal stone) is essentially a female phallus, a symbol of fertility with the shape of a uterus or a vulva. The split reveals the soft, vulnerable innards, an organ holding blood and placenta.

In the physical sense, a birth is a separation of mother and baby, one person made two, as in “Materia Medica”: “the wound of birth tore us in two/we regarded each other//across unfamiliar air.” In the metaphorical sense, birthing is also a spiritual split, as in the poem “Memoir,” in which Rabins overlays a Kabbalah concept on the experience of a C-section birth:

And once, no, twice I lay on the birthing-table and a stranger

cut me open, my body falling into two halves,Compassion and Judgment.

Compassion and judgment, according to Kabbalah, are two opposing impulses in the world which we are challenged to balance in our lives. In many of the poems we can see these undulating powers in the small daily mistakes of parenting; for example, take “The Monastery of Motherhood”:

it’s hard to face

my ugly old self again

whether by the pig farm

or metropolitan crossroads

but the hardest is alone

with children

I’d cut my lungs out for her

but then I spray her

in the face with the hose

when she claws for the baby

and so in the monastery

of motherhood I find the devil

in my own heart

Yet, despite all these failures—the worst of all being our mortal failure to pass on immortality to our children—the new self is woven into the continuum of humanity through the act of motherhood. Ancient female deities appear in a few of the poems almost as ancestors, and it seems at times that the speaker tries to hold on to something that flows through her, like a wave, a contraction, old self and new self, time and wisdom. Rabins is able to place the reader in the tiniest moment while at the same time opening an expansive vista on humanity—which in itself makes Fruit Geode a collection worth exploring.