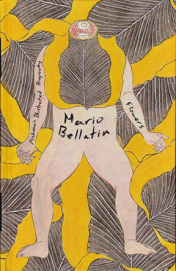

Mario Bellatin

Mario Bellatin

Edited by Daniel Parra

Translated by Kolin Jordan

7Vientos ($19.95)

by Greg Baldino and Adrian Nelson

In the classic fuzzy logic problem, a boat undergoes a series of repairs, replacing each plank of wood one at a time until the entire boat is made of new wood. The question is asked if it is still the same boat, and if not, at what point during the repairs did it become a new one? Mario Bellatin's two novellas, collected in a flip-book edition with the original Spanish and a new English translation, address a similar question of loss and identity: How do we change in the face of loss?

The narrative in Flowers is divided into a series of linked vignettes, each named after a different flower. Haunting the stories is the drug thalidomide, an immunomodulatory drug once prescribed for morning sickness, which resulted in a generation of babies born with missing or deformed limbs. Among the recurring characters is a writer (never named, though implied at times to be an analogue of Bellatin) with a prosthetic leg decorated with jewels. Elsewhere in the wandering fragmented narrative are the troubled affairs of the “Autumn Lover,” a person who is attracted to elderly people (and dresses as one); the work of Dr. Olaf Zumfelde and his assistant Henriette Wolf, which seeks to compensate victims of the drug; the mosque that the author frequents and the dervishes therein; and the brief glimpses of others struggling to navigate a world where their sexuality, their religion, or their disability separates them in solitude. Each of these pieces of interrelated flash fiction is written in a precise and concrete style, dream diaries transcribed into police reports. This stylistic detachment allows the reader to view the players in this modular drama objectively, from all angles; there are no victims or heroes, only humans trying to live and understand their lives.

Mishima’s Illustrated Biography acts much like the second half of Dostoyevsky’s Notes from the Underground, reflecting and magnifying the ideas and themes of the stories in Flowers. In no way an actual biography of the controversial Japanese author, the story begins after Mishima had committed ritual seppuku following his personal militia’s failed attempt to stage a military coup. The author—sans head—attends a university lecture on his own work, and then proceeds to carry on with his life in the company of his disciple, Masakatsu Morita. Substantially more surreal than Flowers, here the novella takes the idea of loss of limbs as metaphor to a parodic extreme, examining what happens to a life when the drive of the soul is entirely removed. The narrative works because Mishima was a real person who did indeed lose his head; it allows us to consider his life before literally losing his head without requiring an embellished backstory.

Setting aside the desire for linear narratives, the two stories open up to re-viewing the world through the eyes of those it discards or ignores, unfolding petal by petal for them. In Spanish, Bellatin's prose contains echoes of the surrealism of the other literary greats before him—Gabriel García Márquez, Juan Rulfo—but stands alone in some of the things it touches, particularly disability and sexuality. The English translation, though competent, does not quite capture the fullness of Bellatin’s natural voice. But readers not fluent in Spanish may still catch a glimpse of the world that Bellatin allows to play out: the dream-fragments that one remembers on waking, brought to the language of reason.