Neal Bascomb

Neal Bascomb

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt ($28)

by Samir Knego

In the world of motorsport, it's sometimes said that a particularly fast drive will “look slow.” Neal Bascomb mimics this in his writing as he takes the reader through a given lap; rather than emphasizing its speed, he breaks the lap down to focus on the details of the track, scenery, and driver action. After laying out each gear shift and swerve in painstaking detail, the impressive speed of the lap hits all the harder when Bascomb pans away and says it took just one minute, fifty-two seconds to complete.

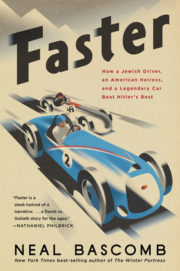

Both thoroughly researched and packed with visceral action, Faster tells the story of René Dreyfus, Lucy Schnell, and the Delahaye 145—the Jewish driver, American heiress, and legendary car of the subtitle. Because they are all underdogs socially as well as technologically, Bascomb argues for the symbolic importance of their win against their Nazi-backed (and staffed) competitors.

Bascomb is interested in the power of stories and remembering, and he frames the book partly in reaction to the Nazi attempt to erase French racing history. Early on in the occupation of France, Nazi officers visited the Automobile Club de France archives and seized all the files. To the librarian, the Gestapo officer in charge said: “Go home and never return here, or you’ll be arrested. We will write the history now.”

To those who doubt the importance of race cars amidst the other events of pre-World War II Europe, Bascomb makes clear the rhetorical value of motorsport and wins. Even before having fully taken power in Germany, Hitler saw Grand Prix racing as key to the Nazi cause, both as a recruitment tool and as a proving ground for Aryan supremacy and the Nazi government. The Nazis funneled significant amounts of funding to German automakers, and for several years German teams were unbeatable in part because they were able to outspend other manufacturers by miles.

Led by team leader, funder, and occasional rally racer Lucy Schnell, the French Delahaye team attempted to challenge this status quo. The story reaches its climax with the 1938 Pau Grand Prix, where René Dreyfus won in the Delahaye, becoming the first driver and car to beat the Nazi-backed teams in several years. Going into this final chapter, the modern reader is as sure that Dreyfus will win as the German teams had been confident of winning in the preceding years. It should be a moment of triumph, but amidst the clear symbolic power of the Delahaye win there is an air of melancholy, since we know what is to come in Europe and beyond.

After the high of the decisive win at Pau, the Delahaye had another Grand Prix win before German cars swept the rest of the season. Bascomb notes that the Delahaye never really lived up to expectations; from a purely technical perspective, the story is one of failure, or at least mediocrity. But the larger story Bascomb tells is not one of engineering prowess, but of people and the symbols they hold dear.