by Kevin Carollo

There must come a time when established poets are no longer edited by others, when they become their own muse and judge, when it is only they who shepherd the differentiated flock of a collection of poems from start to finish. Jorie Graham and Susan Howe, two of the headiest and heaviest poets writing today, must have arrived at the stage of their verse lives—the term “career” feels inappropriate, reductionist—where they find themselves in conversation with ancients more than contemporaries, with the past more than the future, with who one was and is as a human being more than who one might become as a poet. Perhaps the conversation naturally turns to the sublime subtleties of language itself, in turn inciting a poetry that generates its own anxiety of influence, its own metaphysical stakes, its own mode of being-in-the-world—as well as the equally urgent need to prepare for leaving that world.

Such a poetics necessarily embodies a profound loneliness at the heart of human poetic experience. The freedom from editorial constraint in the all-too-human world of publication, awards, and accolades must run up against the all-too-rare sensation of being deeply read or lovingly understood. As with poetry, so with everything: it is never what it is. Both Fast and Debths come from this eerie and elemental no one’s land of late-stage collections. Graham turned sixty-seven this year, and Howe turned eighty. It is a time to ask one’s gods if a lifetime of verse matters.

If this sounds like a rather baleful endeavor, akin to articulating a sickness poetics unto death, so be it. Such loneliness must feed off of a kind of Kierkegaardian hunger—a hunger to know what it all means at the proverbial end of the day, to desire some existential answers at the end of the poem, and ultimately to feel the inevitable not as some telos of illuminating clarity, but instead as a dynamic-albeit-absurd conundrum—a god always moving farther away as we try to approach her. We are our own editors, and the joke is on us.

In practice, each poet’s approach diverges in crucial and delectable ways. Graham’s latest collection derives from the always-imminent possibility of resonant errata, such that any recombinant phrase, paratactical assertion, or metaphysical line of flight might induce revelation. Each poem comes out of a principle of language as inherently liminal, yet limitless in its marginalia, a rockface wherein lodged multitudes of mini-poems always-already wait to be excavated like living fossils, or some hidden historical record of an intimate-yet-universal “We” who “lost all the wars” and “are in some strange wind says the wind. Are in the enigma of / pastness.” The poems seem so deliberately and painstakingly overwrought as to create densely accreted layers of language, coeval palimpsests of meaning.

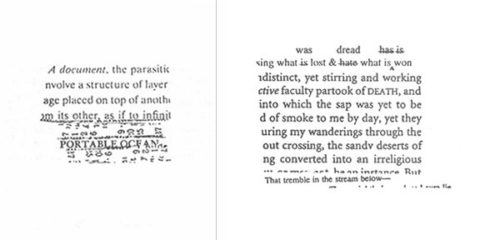

Howe employs a poetics that extends beyond erasure into the realm of textual deformation and hermeneutic dissolution. Short and allusive poems eventually give way to words cutting, pasting, and morphing out of control. Such poems metamorphose into manifold compositions decomposing. Eventually, one moves beyond reading English and into an altogether different kind of perceptual experience. Alterity as epiphany, ecstasy as ek-static, transgressively outside oneself, beyond logos—to watch Howe’s found texts increasingly mutate on the page is to have a universe of elemental word smudges revealed, cosmic revelations sifted through a sieve of poetic devolution.

On another level, both poets are intent on detailing a poetics of thanatology. Graham ritually attempts the impossible by tracking the often-microscopic intricacies of her father dying as if in real time. While titles like “Reading to my Father” and “With Mother in the Kitchen” may suggest a more conventional confessional approach to the subjects at hand—i.e., family and death—they employ the same macrocosmic and metaphysical obsession with the physical body as “The Post Human” or “Incarnation.” In “From Inside the MRI,” single syllables like if or yes or hi knock repeatedly on the door of one’s brain MRI-style, while nagging questions are not so much answered as activated, with directional arrows simultaneously directing and disrupting the flow of the poem. A bird or ringtone appears at the end of this staccato portrayal of a routine and largely unenjoyable medical procedure, but the poem’s existential matter-of-fact diagnosis comes in half of the penultimate line: “It is a nightmare. You are entirely free.”

Certainly, titles are important. The polyvalence of the word “fast” allows for the contradictory impulses of speed and stability, as well as the hunger acknowledged and ritually thwarted by the practice of fasting. Life truly goes by so fast, but there will also come a time when we no longer hunger for it. In this vein, the poem “To Tell of Bodies Changed to Different Forms” asserts: “We / were where it was meant to arrive. Weren’t we? It went by too fast. Hard and fast. A kind / of porn.” In my mind, however, the undeniable aphoristic truth of the poem comes half a page earlier: “We will never be happy with the body.”

Similarly, Debths incorporates the polyvalent notion of indebtedness, but also allows the silent “b” to be inverted, such that Howe intimates various depths to be plumbed—and, of course, deaths to be accounted for, i.e. debited. To merely cite here from the folded, spliced, and collaged layers of partially erased primary texts might unduly privilege the legible, i.e. that which is viscerally understood as representing meaningful English. Instead, feast your eyes on a couple of brief examples, by no means the opaquest of the bunch. The first poem involves a sort of parasitic palimpsest on top of a blurred “PORTABLE OCEAN,” while the other presents a kind of exodus or pilgrimage through the valley of death with a life-giving “tremble in the stream below” the earth of the poem itself.

It is ineluctably pleasing to watch surface meanings give way to a deeper kind of metaphysical archeology, one in which all language and being are radically and dynamically contingent. Plumbing the depths means embracing the metaphysical endgame of language as ultimately moving beyond meaning. Meaning in ruins, being in runes.

Graham as well concentrates on the myriad debts and costs involved with living and dying. Indeed, the medical profession establishes the harrowing metaphysical terrain through which we ultimately pay our debts to society—first with our lives, then with our deaths. Meaning is a ghost in the machine of being.

Sometimes she announces the concept with an imperative and idiomatic play-on-words, as in “Change! The debt ceiling has shown itself to us.” Or, as in “Prying,” debts are accounted for with a series of admissions: “So I / accede, I sign the dotted line, they will keep track / of everything, my breaths, my counts, my votes—invoices, searches, fingertips—don’t I / know you / from somewhere says my heart to the machine reading me out.” Yet again, an irreducible kernel of truth comes before this extensive (and perhaps excessive) medical-political-metaphysical delineation of surveillance: “To survive, you need to be / completely / readable.”

Howe begins Debths with a relatively straightforward foreword, albeit one employing the antiquated spelling “Foreward.” Though one might glean some idea of the inspiration and methodology driving the poems that follow, its exegesis also offers wayward epiphanies such as “there are names under things and names inside names.” My favorite poetic revelation from this section comes from inside a short paragraph: “Lilting betwixt and between. Between what? Oh everything. Take your microphone. Cross your voice with the ocean”—in other words, what being oceanic means. The intertextual erudition underpinning all of Howe’s work is enabled—and ultimately exceeded—by an unquenchable and wide-eyed curiosity, an infinitely open-ended empathy, and the fervent belief in the notion that “only art works are capable of transmitting chthonic echo-signals.”

Perhaps art’s greatest task and ultimate reward lie in such slow, lifelong revelations. To pay witness to the profound depths of humanity, to take absolutely nothing at face value, and to work the language as if our very being depends on it.

Graham ends her collection thusly: “they have / known what to find in the unmade / undrawn unseen unmarked and / dragged it into here—that it be / visible.” With an otherworldly grief and ecstasy, Fast and Debths offer incontrovertible ontological proof that there is still so much left to fathom, to unearth.