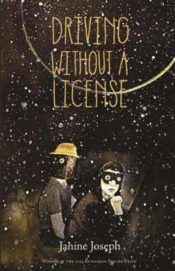

Janine Joseph

Janine Joseph

Alice James Books ($16)

by Steve Fellner

Janine Joseph’s debut collection of poetry Driving without a License couldn’t feel more urgent. Propelled by the topic of immigration and filled with heartbreaking relevance, the book still manages to treat the subject with a unique sense of humor that feels wholly appropriate. Courage and a side-glancing wit unite, making Joseph’s collection a necessity.

First person, childhood narratives make up a good amount of the poems here, and, in the wrong hands, this could yield a mawkish tone and one-dimensional characterizations. Joseph manages to transcend any of those dangers, inspiring a jitteriness in the reader. This unnerving comedy doesn’t ward off the drama; rather, it adds another layer of intensity to the book’s depiction of very real terrors.

For example, in a poem called “Extended Stay in America,” Joseph writes about a Filipina mother who instills in her daughter the fear of being deported. Hiding in a hotel room after barreling through a Pick N’ Save to gather food and a cordless telephone, the daughter discloses the following:

I cracked

the window, left shoe marks

on the motel sheets.High on Astro Pops

and candy cigarettes,she said, Now

your classmates will know.

Comedy shows itself in a variety of ways. In the poem “Comeuppance,” Joseph begins with a conceit ripe with slapstick: “Maybe if when I dove into the pool my head came up / swollen and lobotomized and cuckoo in its nest.” Through the anaphora of the word “Maybe,” almost without us even noticing, she lands with an expression of unfortunate disappointment: “Maybe if my parents had signed here and signed here and signed here.”

Attracted largely to couplets, Joseph does rebel at times, allowing her poems to zigzag across the page. This could be seen as a distinctly political act: her words refuse to be rounded up and immobilized.

One of the highlights of the book is a crown of seven sonnets focusing on marriage, family, and immigration. There’s a real inventiveness in the choice of rhyming words, such as “apelike”/ “turnpike.” In this crown, she surprises us with a number of different rhetorical strategies. For example, in the fourth sonnet, “Advice for Newlyweds,” she uses a strict list of commands:

Never guess down the wrong road, naturally.

Do not gesture or stumble saying Sweet-

heart. You can be prepared to fail if you fail

to prepare. It is just an inspection.

There is nothing you need to know by heart.

The issue of time is another important theme here. For the undocumented immigrant, it is a challenge to move quickly enough not to be captured by an unjust political system. Conversely, the danger of not moving slowly enough is losing the opportunity to enjoy the freedoms and pleasures to which everyone should be entitled.

The only poem in the crown that employs an ampersand is the last, “Establishing Residence,” which makes complete sense: this punctuation mark always creates speed. Against many obstacles, our newlyweds manage to find peace in the most mundane domestic chores together, and Joseph shows us the wide-eyed joy in their peaceful (at least for the moment) routines:

Ten a.m. & he’s up & she’s up &

they are rotating the couch cushions so

the suede won’t wear. They stroll, they lunch at noon,

they touch. They wring the sheets, they giddyup.

This is us, she says . . .