by Julien Poirier

For many poetry readers, Dispatches from the Poetry Wars was the best website of the Trump era. Visiting its home page was like limping into a port in a storm, only to be harassed, sweet-talked, and propositioned on your way to the nearest dive, where some incredibly erudite but fantastically longwinded “traveler” would bend your ear for hours about the Surrealists, Oulipo, or Conceptualism before ripping off his toothless rubber mask to reveal a mild-mannered professor in a Columbia windbreaker, who would then astound you by whipping out a carbon-dated copy of a John Ashbery poem proving that Ashbery himself was actually a 42-year-old Scottish witch with a soul patch living on Corfu.

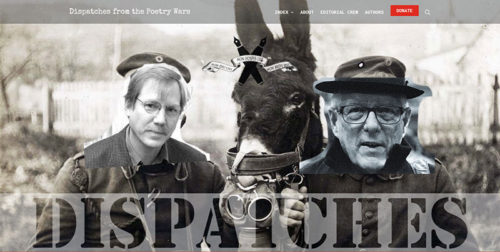

Dispatches was live from April 2016 until May 2020. Populated by hundreds of essayists and poets (some of them entirely fictional), it was a hive of self-stinging contradictions—illuminating, infuriating, principled, irritating, reflexively satirical, idealistic to a maudlin degree and helmed by two shadowy figures calling themselves Fric and Frac, known in their earthly bodies as Kent Johnson and Michael Boughn. Egalitarian, and with a special contempt for glad-handing elites, Dispatches may have flowered in the toxic mudslide of the Trump years but its roots tapped the subsoil of Reaganism and the U.S.-backed genocidal wars in Latin America—where Johnson, an infamous provocateur in the poetry world, had worked and struggled—wars which coincided with the rise of the professionalization (and sterilization) of poetic dissent in the North American university and street. In short, Dispatches was a daily attack on the complacency of a dying empire’s poets—bent, it seems, on irritating everyone, even its allies, along the way.

Beginning a few months after Dispatches went dark, and coinciding with the recent presidential election and Trump’s attempted coup, I conducted this interview with Johnson and Boughn over email.

Julien Poirier: The title Dispatches from the Poetry Wars is the perfect PB&J combination of Michael Herr's Dispatches (his brilliant book about the Vietnam War) and the so-called “poetry wars” of the 1970s and ’80s, where the newly fledged Language Poets (especially Barrett Watten) and a less self-critically soulful motley of poets who came up in the ’60s (especially Tom Clark) went at it in the trenches of Bay Area papers. Your acerbic bent as editors suggests you think the wrong side won. Were the Language Poets the vanguard of today's “professional” poets, and if so, did you start Dispatches to vanquish them?

Michael Boughn: Well, I don’t think the word “win” signifies in a poetry war, but even if “the right side” “won,” Kent and I would still be acerbic. We can’t help it. It’s congenital. We got tested and we were both positive for acerbicness.

That said, I am not even sure what the phrase “Language Poets” refers to. I know this is an old complaint. It used to refer to some poets who published in Charles Bernstein’s and Bruce Andrew’s LANGUAGE (forgive me if I omit the tedious equal signs) Magazine. After that, it kind of morphed into a portmanteau phrase, and all you had to do was say something arcane about non-referentiality and you could call yourself an L-Poet. But even that has evaporated. Some of the former leaders now write ironic doggerel and get big prizes for it. The issues with referentiality seem to have disappeared in the race for the various prizes and positions that have been showered by The Academy and The State on the remaining team members.

I think that poetry got mugged in the ’80s. After poetry broke out in 1960 (to use a symbolic date), a general opposition to the advances of the New American Poetry arose in multiple corners of Plato’s Academy as it sought to regain control. Two major fronts opened up in the Institution: the creative writing front (right wing) and the avant-garde front (left wing), both of which sought to foster skepticism around the advances that Donald Allen’s anthology announced. Our initial resistance had to do with people claiming that the poetry wars were over even as they continued to attack or attempted to assimilate the poets (Creeley, Olson, Dorn, Baraka, etc.) who were central to the NAP. So, no, we didn’t start Dispatches to vanquish anyone. We’re more lovers than vanquishers. We just wanted to set the record straight.

Kent Johnson: The true forerunners of the current professional poetry class, of course, were the New Critics: the cultural Falange (in fairly literal sense) that the New Americans set out to resist with poetic and counter-cultural Molotov cocktails. The Language Poets, on the other hand, who proclaimed themselves more vanguard than the New Americans, turned out to be more like the prodigal sons and daughters of the New Critics. They returned home, during the Reagan and Bush Sr. era, after quickly exhausting their “avant-garde inheritance.” They’ve been welcomed with embracing arms (even if with some reservations) by the Creative Writing and high-theory types at The Academy.

More specifically: After throwing a few tomatoes here and there at the 1970s Deep Image/Confessional amalgam of early MFA program history, and splicing naive “Marxist” derivations onto now-defunct French theory, they got a few well-placed introductory essays directed their way in the 1980s (not least from the Neocon critic Marjorie Perloff, whose attitudes regarding race seemed to share a good dollop with those of Allen Tate), and quickly dropped their outsider pretenses, setting out on their “Long March into the Academy” (a phrase spoken to me, in fact, by Bob Perelman, after I’d given a friendly paper about the group at the MLA in New Orleans). The start of that march, interestingly (or predictably) enough, was roughly concurrent with the fall of the Berlin Wall and the first Iraq War. The rest is history. The Language Poets, along with their “post-avant” progeny, have succeeded in becoming, as I’ve said elsewhere, the most academically entrenched poetic formation since the glory years of the Sewanee and Kenyon reviews. We are waiting for our next New American Event now. Not that anyone should be holding their breath.

That said, Dispatches was not in any significant way a response to Language Poetry. By the time Mike envisioned Dispatches, the Language Poets, in the sense of any kind of vibrant, relevant current, were gone.

JP: I guess the Language school still interests me because it was so self-consciously political. Politics in the United States are terribly self-centered, and poetry politics seem to mimic that. By the time I tuned in (in the early ’90s), everybody was at everybody else’s throat while pretending to a seething civility; in the timeless fashion of a well-fed intelligentsia, infighting among adjacent poets took precedence over solidarity with poets on other shores. In contrast, Dispatches seemed intent on revealing an international poetic underground, though at the same time, it seemed to revel in a more-radical-than-thou skewering of perceived enemies. Was this side combat central to your plan, or would a total focus on solidarity among allies have gone deeper?

KJ: You know, having said the above, let me offer this: All due honor to the LangPos. Much of their critical stuff looks dated now, even sometimes humorously so, but that’s because they had ambition and set out to challenge some things. They certainly did shake things up in provisional ways for a couple decades and raised some good questions, even as their targeting of the New American Poetry as some sort of logocentric, semi-Romantic tendency requiring post-structural rectification turned out to be grossly misguided. And of course, their absorption (eagerly self-invited, in hindsight) into the sub-cultural institutional Moloch is now a done deal.

MB: And I would question what you mean by “political.” Mouthing neo-post-Marxist theoretical claptrap about syntax changing the world while jockeying for positions at prestigious universities does not count as political in my book, at least not in the sense you mean. Were they organizing for anything other than their personal aggrandizement? Did they ever actually do anything? I mean DO as in get off your ass and into the streets kind of do, where you actually risk something. Ginsberg’s King of the May shtick was way more political than anything coming out of the L-Po contingent.

KJ: Well, some of them did travel regularly to China, to attend poetry conferences, thus openly abetting the Chinese Communist Party’s “soft power” strategy while writers and artists like Liu Xiaobo were rotting away in prisons. That’s kind of “political,” you could say.

But on your implied possible mismatch, Julien, between Dispatches’ solidarity with a “poetic underground” (a solidarity that was real, yes, and more internationalist than any U.S. poetry journal of its time), on the one hand, and Dispatches’ insistent “skewering of perceived enemies,” on the other, I would offer a historical example of a vanguard formation that engaged in precisely such a contradiction and bet its life and principles—both aesthetic and ethical—on the gamble: The Surrealists, under the guidance of Breton and Péret, in their prolonged struggle against not only the official lit culture of 1920s and ’30s France, but against the literature of international Stalinism. You can’t come up with a poetic movement that more consistently defended revolutionary principles, not just in art, but in political action. Nor can you come up with a poetic movement that more consistently and joyously dove deep into the literary politics of its time, petty and “divisive” as it might have seemed then, to many. There is no incompatibility whatsoever between the two modes of attention. The politics of poetry are inseparable from the poetry of politics.

MB: The skewering of “perceived enemies” doesn’t quite match my sense of where we were at. We were not focused on “enemies,” perceived or unperceived. We were focused, as satirists, on the moral bankruptcy of the authorized poetry culture—that being the poetry culture financed by the state through its institutions, be it PoFo, UPenn, Harvard, or the Library of Congress. That is the business of satire, a proud and essential genre now largely lost to overwhelming sentiment and linguistic razzle dazzle.

KJ: I’ll just end by pointing out that this sentence from you, “By the time I tuned in . . . everybody was at everybody else’s throat while usually pretending to a seething civility,” is still just as true, if not even more so now than then.

JP: I agree with you in spirit (and with knife in my teeth) that the fat boat of institutional poetry was ripe for a boarding and full pirate treatment on the high seas. But I'm not convinced that satire is the best weapon to use against cynics disguised as florists. What did Dispatches hope to achieve by tenaciously attacking an institution such as the Poetry Foundation rather than giving it the middle finger, once and for all, before turning its full attention to fostering a new nation of outsider poets with no time to beat dead horses?

MB: First off, I think that our rhetorical toolbox at Dispatches was more diverse than you suggest here. Yes, satire was central to our project. Both Kent and I are huge fans of Ed Dorn, who, along with Mark Twain and H. L. Mencken, is one of the U.S.’s greatest literary satirists. He famously proposed, “Entrapment is this society's / Sole activity . . . / and Only laughter / can blow it to rags.” That was one of our guiding principles, just as his Rolling Stock was one of our inspirational models. That said, we wrote in varied modes, depending on the circumstance, and had numerous targets in the Official Poetry Economy. The Poetry Foundation, or PoFo, Inc., as we affectionately tagged it, is crucial because it is the door through which Wall Street and the National Security Apparatus entered the poetry scene and, with Ruth Lily’s $100,000,000 gift, effectively took it over, organizing both the right and left wings into a manageable unit lined up with their hands out. Hardly a dead horse. Maybe an undead horse—which definitely deserves to be beaten. As for fostering a nation of outsider poets, one of the ways you do that is to continually point out the moral and artistic corruption of the Official Poetry Economy while providing an alternative space for something else to coalesce.

KJ: Um, yeah. Preach.

JP: Well, I'd argue that the “Culture Industry” is a parasitic illusion. Surely there's an outside to it, and as long as poets trust each other we can get there together. Of course, that trust must be earned, at least according to the dominant leftist narrative that has shaped poetry politics during the endless war of the current century. In a pinch, straight white male poets can't be counted on to do much but forward their group's own agenda, so the narrative goes. But in terms of intraparty conflict, the last few years have been especially fierce: what with the “No Manifesto” (avant-garde precursor to the “Me Too” movement) and the thriving “Black Lives Matter” movements, straight white males (poets among them) have been taken to task for—to put it charitably—a congenital lack of self-reflection. Dispatches was active throughout the pitched battle between ascendant white supremacy and woke eloquence. How did these cultural struggles shape your joint editorship?

KJ: Julien, Dispatches—and starting with Dispatch #1—declared itself a Temporary Autonomous Zone (TAZ). We never said there was no possible “outside” space. We were all about the urgency of being outside, however uneasy and precarious that outside surely is. But we were also clear-eyed that it wasn’t simply a matter of just “making a choice” and retiring to a commune in the country. It’s hardly that easy, given the reach of the institutional/professional driftnet that’s so successfully ensnared the bulk of schooling fish, as it were. The well-travelled Gramscian term for the matter confronting us is hegemony. And poetry—right and left, “mainstream” and “avant”—is living in some damn pernicious hegemonic times. Much more so than rebellious poets during the New Critical period of not so long ago. Can we imagine a New American counter-current of resistance emerging like that all of a sudden today? No, we can’t. And it will take a good deal more trench work, or some kind of help from bigger social forces, to kick poetry off its protracted suck on the teat of Prizes, Grants, and Tenure.

Nor did we, to be sure, ever claim we were totally safe from getting caught up in sucking on it ourselves. No one is safe.

MB: Personally, I know all that recrimination and incrimination stuff goes on, but I try to ignore it as much as possible. Mostly in our bailiwick it has to do with equal distribution of art booty. I have no stake in it. I don’t want any of the prizes, awards, grants, or other tokens of the State’s affection. So, I don’t have to deal with the squabbles over the representation of the dispensers and recipients of art booty.

Like Kent, I came up during a time when we, those of us involved in the resistance, all became increasingly aware of the ways in which the dynamics of patriarchy inflected our relations with each other. We took on the task of trying to straighten that stuff out as much as you can when you are, as you put it, inside. Actually, as Kent said, there is no “inside and outside.” That idea is pure poison. It leads to the Mechanics of Perfection, and then we turn on each other and rip our mutual throats out in the frantic quest for some kind of purity.

We are all part of It, aren’t we? Limits are what we are inside of, to quote Charles Olson. In the course of our lives, Kent and I have fought to be further, to move the limits out. That’s how Emerson has it. That we are all capable of being further, a further person. Stanley Cavell calls it Emerson’s moral perfectionism. Not that you can be perfect. But perfectionism is the will to keep trying, to become a new person, a further you. I do my best to live a life that is true to my sense of the struggle for justice, for equality, for dignity and respect in my relations with others. I often fail, but as Samuel Beckett suggested, we should all fail, fail again, fail better. Emerson would agree with that. If I am called out for some failing, I listen, consider, and try to do better. How else to get through this vale of tears?

Kent and I went out of our way to make Dispatches welcoming to everyone, including those who disagreed with us and who were critical of our very existence. In the beginning, especially, when everyone’s dander was up about how rude we were, we published letters and essays from people who questioned us and our mission. As for diversity of representation, if there were any notable absences in our lineup, it was not because of any exclusionary prejudice on our part. It was because some people were not very comfortable with our mode of activism and chose to stay away. Some were alienated by the word “war.” Ha. Here we are face to face with judgment which dismisses “war” as the fantasy of macho boys. Well, there may be some of that. I am far from perfect. Kent and I are boys. We admit it. But does that leave us helpless tools of patriarchal control and manipulation? And further, is there only one (negative) sense to that very ancient word, “war”? I leave it to others to judge what we did with our war. But I have no regrets from that whole four-year run.

Let me just say before I shut up that I think the real enemy is the tendency to generalize everything. It’s an affliction of the imagination that destroys the detailed world of actual value and replaces it with a world of cutout figures ready made to fit into your categories of absolute good and bad, a smooth world that gives rise to smooth poems. William Blake called it the state of Ulro, a low-level mode of human relation. When you try to shake it up, you are accused of being a warmonger.

JP: I want to talk more about the “outside” or “other” space that Kent brings into question. Its contours do feel quasi-religious to me. At the same time, it feels quite real to me since I live in that space and can easily recognize my compatriots. The surface of Dispatches may have roiled with debate about poetry politics, but its darker undercurrents seemed dedicated to rocking the boats of unaffiliated song. Am I right? You both seemed dedicated, ultimately, to freeing the poetic art from the “poetic war.”

KJ: I don’t think so, Julien. The poetic art is never free from the poetic war. All truly new paths through history, all real breakthroughs in the poetic field, are entangled, in some measure or other, with an aspiration (sometimes fruitful, most often shattered) to recover and enable that life of “unaffiliated song” (a very useful phrase, thank you). To challenge the stultifying and ossified with something unsuspected and (at first) incomprehensible is the dialectical history of all the arts, right? And it includes discovering the “unaffiliated” in the old and the forgotten, disinterring its spirit. Make it New, as the saying goes.

MB: Deleuze’s suggestion was that we should “Bring something incomprehensible into the world!”

KJ: Now, it’s key to remember that any “outside” or “other” spaces that are created in such gestures don’t long remain pure and autonomous, if ever they were. Part of the dynamic of the poetry wars that are always with us is that rebellious instances are entangled, coerced, and absorbed not long after they emerge.

MB: Since we are riding this inside/outside thing, let me remind us that the poetry war takes place inside before it takes place outside. The struggle to remain true to poetry’s mission is a spiritual ordeal as much as it is a public engagement. And it is continual.

KJ: Yes. It’s dialectical, through and through. Recognizing that the ordeal is impure, contingent, and provisional doesn’t mean one just waves surrender. One keeps firing into the dark and tries to extend the resistance as long as one can. Because one knows, too, that others will start over. Otherwise, we’re stuck inside the Museum in one eternal nightmare of the soul. I mean, who wants to stare at William Bouguereau or Donald Judd their whole life, right?

Temporary Autonomous Zones: The “Temporary” in that phrase is not to be missed. Because the term marks both the tragedy and the honor of the unceasing attempt. Its comedy, too, let’s hope.

JP: So are we at a point now, in the midst of inchoate instinctive global fascism and climate collapse, where more poets will free themselves from the market? Or the opposite? Is the inertia of capitalism powerful enough to sink the pennywhistle of liberty?

MB: There are a lot of assumptions in your question that I am not sure I agree with. For instance, inchoate global fascism. The fascism (and proto-fascism) looks pretty choate to me as it surges around the globe right now. It’s definitely on a roll in the wake of the destruction wrought by neo-liberalism and globalization over the last fifty years. But we must never forget that fascism is not just “out there.” Robert Duncan was so clear about this. He warned us over and over. None of us are innocent or untouched by evil. The minute you forget that, you become complicit. And secondly, whatever the temptation, I think we have to be careful not to impose the past on the present. For all its similarities, this is not 1933. And although we have more than enough evidence of climate change, climate collapse is just speculation. We know climate change is critical, but we only have models of how it is going to evolve. And models aren’t knowledge. There are plenty of problems, political and ecological, that we have to address as poets. But we need to stay open to the specificities of the emergent reality we are entangled in rather than reacting to projections of our fears and anxieties. That’s what poets are responsible for, keeping the open in front of us all.

As for liberty, it’s important to remember that it is something one takes, not something that is given. Under the regime of capitalism in its many evolving forms, which we also call modernity, something called liberty has been exchanged as a social/political commodity and regulated with strict codes. It is a controlling trope in the U.S., as we saw during Trump’s attempted putsch in Washington D.C. Don’t tread on me because I want to tread on you first stages itself as liberty, but is really an eidolon, a false image. Liberty circulates freedom, it doesn’t restrict or contain it.

Diane Di Prima famously said that the only war that matters is the war against the imagination. You could rejig that to say further that the only liberty that matters is the liberty of the imagination to embrace liberty. And embracing liberty extends it, circulates it. Poets know that because it is the lifeblood of their art, its fundamental challenge and offering, a reality they face with every word they write. To get to that place is not easy. As I’ve said, it involves a spiritual ordeal. You can’t take a course in it. Or workshop it. It’s a quest. So, I suspect that whatever happens politically, most people writing marketverse will keep on writing it. And poets will keep on writing poetry. They have to. That’s why they are poets.