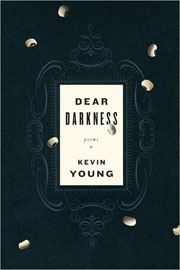

Kevin Young

Kevin Young

Alfred A. Knopf ($26.95)

by John Herbert Cunningham

In concluding his essay “Mixed-Up Medium: Kevin Young’s Turn-of-the-Century American Triptych,” which discusses Young’s first three books—Most Way Home (1995), jelly roll (2003) and Black Maria (2005)—Rick Benjamin states:

In all of Young’s books, so much depends upon that familiar American idiom that frames our history and that at once testifies to and witnesses in its many voices, versions, and vernaculars; heartbreaking losses and betrayals; unspeakably sweet stays against such experience; deep repositories of exploitation and brutality; freedom, as it always is in America, a dream deferred, yet also, perhaps, just around the bend; impermanence itself the promise of an end to suffering (but also, of course, to joy)—a rich, complex, contradictory idiom and legacy to be sure. . . . when either entering or leaving a book by Kevin Young you are also in the presence of something unmistakably new. This work is a jam session in progress: Coltrane out on a limb for thirteen minutes with that familiar melody of “Favorite Things,” but in a way you’ve never heard before, dropping finally, but only for a moment, on dogs barking and bees stinging. He’s playing our song: set ariff by reading; hanging on the next note.

Young opens Dear Darkness with a blues:

My mouth a harp,

heart a harmonica

in coat pockets so thin

the wind

is my accompanist.

This is poetry that sings, that swings with the sweet, low sound of Ellington at the Cotton Club, 1941—the place where “Only the stones / call me home.”

Young’s poetry rages against racism, not allowing the jibes and taunts of school children to be forgiven or forgotten, nor anyone to hide beneath the veneer of ignorance. He reminds us that behind this veneer lies the adult world where children are taught to be overtly (or more often, subtly) racist, where, if those in charge allow racist epithets or jokes to go unchallenged, that behavior gets reinforced and encouraged. As he says in response to the joke “What do you get / when you cross a black person // with a Smurf?”

And when

you see that boy whose last name

I don’t seem to remember, be sure

to tell him that this here Smiggercould care less yet could never care

more, that my blue

& brown body is more

than willing to inform

him offense is one hostage

I have never taken.

In the stories Young tells of growing up black and the beauty of that life, poverty exists side-by-side with good nature. In “Eulogy,” he writes “All talk / is lucky. Just ask / my grandpere, growing / into earth, half- // French, all man- / drake screaming when pulled / from its roots.” He raises his voice in the blues and humor—those things that assist a minority suffering discrimination to survive, to shield themselves from the hurt. Feel the rhythm of “Black Cat Blues”:

I showed up for jury duty—

turns out the one on trial was me.Paid me for my time & still

I couldn’t make bail.

We’re not talking here about the rage that informed Amiri Baraka when he was LeRoi Jones, just a recognition that the more things change, the more they remain the same, only more hidden. This is the message behind “Adolescence”:

Gravity is screwed

up—nothing stays

when put down

like the class

outcast, or elseseems so heavy

it won’t budge. Sit

in your room, not sent,

& wait for weightlessnessto overtake you.

Is this Ellison’s Invisible Man recast in verse?

At one point, the blues were frowned upon as something from a past that the black man was trying to rise above, to forget in order to move on into a color-blind future. Young excels at making them the basis of his poetic style, proclaiming that the black man should be proud of his heritage. He uses the blues to speak out against racism and discrimination, as he does profoundly in the final stanza of “Up South Blues”:

My daddy’s philosophy

always was

We shall

overcome—

& fresh ammo for my gun.

A couple of poems further on, Young begins to write what he calls “Odes,” but the structure, the rhythm and the sound are not different than what he was earlier calling “Blues”—as if to say there is no difference between the black man’s blues and the white man’s odes, they stand equal in the realm of poetry. Then, in the next section, “Young & Son’s Pawn & Gun,” he writes nothing but odes, with titles like “Ode to Pork,” “Ode to Chittlins,” etc. In the first, he writes: “I know you’re the blues / because loving you / may kill me—but still you / rock me down slow / as hamhocks on the stove”—making it clear where he’s coming from.

At one time, African American poets wrote sonnets in order to demonstrate that they were just as good poets as whites. Along came the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s, which incorporated all aspects of black life and all forms of writing. Kevin Young has returned us to the aesthetics of that renaissance by celebrating these aspects of black culture, jazz and blues being but two stylistic examples, that tell the story of black life in a racist, impoverished society, but that emphasize successes despite hardship. It’s the American story, of course, and Young spins it as well as his great forebears.