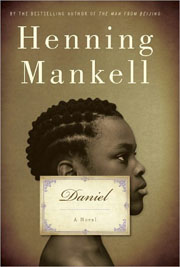

Henning Mankell

Henning Mankell

Translated by Steven T. Murray

The New Press ($26.95)

by Jens Tamang

A story about a white man who brings a black child back to 19th-century Sweden against his will, Henning Mankell’s ethically complex and disturbing novel Daniel has tremendous potential for offense. YetDaniel is a surprisingly delicate meditation on the failures of colonial power, providing a drastic departure from the desiccate Kurt Wallander mysteries for which Mankell became internationally renowned.

Originally published in Swedish in 2000, Daniel begins with a disparaging portrait of twenty-nine-year-old Hans Bengler, an extremely bizarre entomologist bent on discovering an unknown species of beetle. It quickly becomes clear that Bengler—a lonely, drunk, academic failure—isn’t really searching for a beetle, but unattainable dominance: “The world was full of insects which didn’t have names and had not been catalogued. Insects that were waiting for him.” For Bengler, the prospect of finding such a specimen leads him to fantasize about reversing his failure at school, restoring his family’s wealth, bringing his mother back to life, and curing his all-consuming impotency (figurative and otherwise).

When he finally finds his beetle, Bengler’s fantasies prove to be lofty, and in this state of disappointment Bengler adopts a “specimen” of a very different kind. He discovers Molo, a young orphaned boy of the San tribe. Ironically, Bengler—a certified observer of nature—cannot see the trauma registered in Molo’s body, the trauma of having witnessed the slaughtering of his family. Bengler names the boy “Daniel,” hubristically satisfied about having “liberated” him from the savage abuse of his former owner.

Mankell does well to foreground the novel with a portrait of Bengler as a white man whose masculinity is in crisis, a man seized by illusions of his own prowess. Throughout the course of the narrative Bengler comes to represent the failure of benevolence to act as a comprehensive solution to the multifaceted problems with which we come in contact. And Molo’s “liberation” provides an excellent example of Mankell’s ability to illustrate scenes with layers upon layers of ethical complexity.

In Daniel, those who mean to do well can do evil, those who mean to do evil can do well, and everyone is to blame but the child caught in the crosshairs of white supremacy and colonial arrogance. Such ethical complexity shrouds the novel in mystery and the effect is gripping. Coupled with the stark prose that evokes the style of Cormac McCarthy and harks back to Mankell’s roots in the detective genre, it’s definitely hard to put the book down.

Perhaps the most questionable aspect of the book is that, a third of the way through, the narrative switches away from Bengler’s point of view and begins to narrate from Molo’s perspective. Here Mankell navigates dangerous territory, having to face head on the temptation to exoticize the “purity” of Molo’s psychology. Mankell’s handling does, more than once, submit Molo’s narration as a stand in for a half-baked concept of spirituality, one that romanticizes the African body in ways that seem sappy and out of touch. Mankell’s depiction of Molo succeeds, however, when it presents a kind of childlike bewilderment with the arch poise of a masterful writer. When Molo first arrives in Lund, a housekeeper finds him urinating on a potted plant, and Mankell portrays the confusion that arises from the collision of the two worlds with humor, tenderness, and a kind of honesty that reaches a paradigmatic realm of human experience.

At the end of the day, Molo’s narration is not the greatest accomplishment of the entire novel. Rather, the novel is at its best when it succinctly depicts scenes with a blunt realism that still seems intimately woven into the fabric of colonial symbolism. In Daniel, the twin poles of Mankell’s native Sweden and his adopted region of southern Africa come together; when Bengler describes the “viscous mess” of an infected boil running down another Swedish character’s back, one cannot help but wonder if it is just that, or if the boil comes to stand for the infection of colonial power sweeping the globe in the 19th century.

There’s no question about the kind of politics Mankell espouses in Daniel. A radical leftist and a life-long opponent of Israeli politics, Mankell provides an important voice in the burgeoning canon of contemporary anti-colonial literature. Furthermore, the fact that a novel with such potential for problematic material can run through the wringer of critical race theory and come out largely unscathed makes it a must-read for anyone who desires to take a long, hard look at a particular racial dynamic and the bloody history that has stained it.

Click here to purchase this book at your local independent bookstore

Rain Taxi Online Edition, Summer 2011 | © Rain Taxi, Inc. 2011