Claudia Rankine

Claudia Rankine

Graywolf ($20)

by J.G. McClure

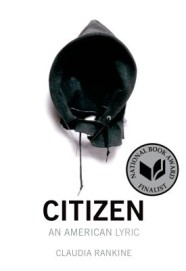

If you’re looking for proof of the urgent necessity of Claudia Rankine’s Citizen: An American Lyric, you might simply look to the cover. The image is of David Hammons’s In the Hood. The severed hood of a sweatshirt—empty, tattered, black—stands against a stark white background. The piece was made in 1993: two years before Trayvon Martin would be born, and nineteen years before he would put on a hoodie, go to the store, and—holding a bag of Skittles and a can of sweet tea—be killed by a man holding a handgun. In the aftermath, newsman Geraldo Rivera would make the absurd and heartbreaking claim that “the hoodie is as much responsible for Trayvon Martin’s death” as the gunman.

So much is encoded in this cover image: the implicit violence of the severing, the absence of a body inside the hood—evoking death and erasure—and its placement against a jarring white background, bringing to mind Zora Neale Hurston’s statement (which Rankine later cites directly) that “I feel most colored when I am thrown against a sharp white background.”

Citizen’s cover is but one aspect of the stunning artistry of this book, the careful and powerful decisions behind each facet of its making. Much has been said about the political importance of Citizen—see, for example, the reviews in The New York Times and Slate—while largely glossing over the book’s artistic achievements, as if what it means and how it means were somehow divorced. But the book’s political power should not be seen separately from its aesthetic power. Rankine has created a text that blends poetry, narrative, essay, and visual art, going even beyond the publisher’s “Poetry/Essays” label into something far more complex and moving: an American Lyric.

One of the many difficulties about discussing the pervasive racism of American life, Rankine writes, is that one does not “know how to end what doesn’t have an ending.” Rather than artificially dividing, ending, or resolving these disturbing scenes into discrete, titled poems, Rankine allows one scene to blur into the next—formally enacting the ongoing and always-unresolved experience of racism. The result is an exhausting accretion of microaggressions. Take the book’s first scene, a childhood memory:

When you are alone and too tired even to turn on any of your devices, you let yourself linger in a past stacked among your pillows. . . .

The route is often associative. You smell good. You are twelve attending Sts. Philip and James School on White Plains Road and the girl sitting in the seat behind asks you to lean to the right during exams so she can copy what you have written. . . .

You never really speak except for the time she makes her request and later when she tells you you smell good and have features more like a white person. You assume she thinks she is thanking you for letting her cheat and feels better cheating from an almost white person.

From the first sentence, the book begins its complicated use of the pronoun “you.” By saying “you let yourself linger,” Rankine establishes a distance from the Self, as if there is a Self that watches the Self act, and dictates what is allowed. Insofar as the “you” is used as a veiled first-person, it creates a further distance between the speaker and her own experience, a distance that Rankine explores throughout the book. But the “you” here can also be the reader, directly addressed, and by casting the reader as the person acted upon, Rankine manages to give him or her a glimpse into the experience of being systematically discriminated against—and even a glimpse is emotionally harrowing. This is one facet of the book’s powerful empathetic project: while reading about the systematic experience of alienation, those of us in positions of privilege are made aware of our alienation from such alienation, precisely because these experiences are not our own.

That Rankine can accomplish such complicated work through the use of a single pronoun is indicative of her strength as an artist. And there is still more—much more—at work in this passage alone. For example, one feels the past as a physical presence, a presence that, “stacked among your pillows,” invades even the most private space of the bedroom. Through unbidden, unexpected associations, the speaker is cast back to a painful early experience: the past, it seems, can attack without warning. What makes the memory especially poignant is how quickly something positive can turn painful: a pleasant smell conjures instantly a memory of racism. Still more troubling, the white girl in the memory apparently thought she was saying something nice: the fact that her intention was not to harm makes the action all the more harmful.

On the next page, we see a photograph of a quiet suburb: white houses, a white car, and a street sign with white letters: Jim Crow Road. The impact is visceral; though one might question the accuracy of memory, the photograph strikes us as unassailable, a fixed record of what is. What could the people who named the street have been thinking? Why hasn’t the name since been changed? Is it possible that those in charge, like the girl in the memory, “mean well”? Have they simply not thought about the harm they’re doing by leaving the name in place—and would such thoughtlessness really be any better than intentional malice? Rankine doesn’t try to guess here; instead, she leaves us to our own conclusions.

This is another powerful theme in Citizen: the inscrutability of intention. Another scene:

You are rushing to meet a friend in a distant neighborhood of Santa Monica. This friend says, as you walk toward her, You are late, you nappy-headed ho. What did you say? you ask, though you have heard every word. This person has never before referred to you like this in your presence, never before code-switched in this manner. . . .

Maybe the content of her statement is irrelevant and she only means to signal the stereotype of “black people time” by employing what she perceives to be “black people language.” Maybe she is jealous of whoever kept you and wants to suggest you are nothing or everything to her. . . . You don’t know. You don’t know what she means. You don’t know what response she expects from you nor do you care. For all your previous understandings, suddenly incoherence feels violent. You both experience this cut, which she keeps insisting is a joke, a joke stuck in her throat, and like any other injury, you watch it rupture along its suddenly exposed suture.

In the face of inscrutable motives by the perpetrator, the victim of racism here begins to doubt herself. In another scene, the speaker wonders if she has “done something that communicates this is an okay conversation to be having. Why do you feel comfortable saying this to me?” In other words: are your racist remarks my fault? The result is emotionally devastating: we see that not only does the speaker face aggressions from outside, but that these aggressions impel her to be suspicious of herself—and the linguistic distancing of Self from Self that we see throughout the book takes on another troubling dimension. We sense the macroscopic scale of such aggressions: widespread and pervasive, beginning in childhood and continuing every day, they have so thoroughly enmeshed the speaker that even in the moment of resisting the assault she is further pulled into it.

The speaker is poignantly aware of her own ability to do harm. A passage describes a neighbor who calls the police because of a “menacing black guy casing” the speaker’s home. It is, in fact, the speaker’s friend, who is babysitting and has stepped into the front yard to take a phone call. The neighbor does not believe this, and the police arrive. The speaker arrives home to the aftermath, the four police cars already gone:

Your neighbor has apologized to your friend and is now apologizing to you. Feeling somewhat responsible for the actions of your neighbor, you clumsily tell your friend that the next time he wants to talk on the phone he should just go in the backyard. He looks at you a long minute before saying he can speak on the phone wherever he wants. Yes, of course, you say. Yes, of course.

It’s a wrenching moment: in attempting to protect her friend from racism, the speaker has unintentionally participated in his silencing and erasure. With the best intentions, she does the very thing she seeks to prevent. The final two sentences leave us with her realization, her lesson learned—and the damage already done.

The passage reflects the brilliance of Citizen. Rankine never shies away from difficult material, and is never reductionist in her consideration of the knotted complexities of race in our country. From its first page to its last, the book is skillfully shaped to produce a haunting experience. Politically urgent, artistically brilliant, Rankine’s Citizen is a must-read for anyone who cares about literature and anyone who cares about America.