Paul Youngquist

Paul Youngquist

University of Texas Press ($27.95)

by Will Wlizlo

Sun Ra believed that the best way to improve the lives of others was to help them imagine an alternate universe. He did so by playing the piano at smoky nightclubs. Over a career that spanned fifty years and 200 albums, he innovated musical techniques and created sounds that seemed to originate in a different dimension. Certainly influential to other musicians, Sun Ra would revolutionize jazz and lay the groundwork for genres as disparate as electronic dance music, classical minimalism, and noise metal. His experimental vision, hope for social change, and enduring fascination with outer space would drive his efforts to lift his fellow black Americans out of dehumanizing poverty and racial injustice.

“Brilliantly and with abandon,” writes Paul Youngquist, author of a fantastic exploration of the music of Sun Ra called A Pure Solar World: Sun Ra and the Birth of Afrofuturism, “Sun Ra crossed the inner city with outer space to create music as progressive socially as it was aesthetically.” He would ultimately land among the stars.

The story of Herman Blount, who would later change his name to Sun Ra, starts on Earth. While Blount maintained for his whole life that he was sent here from the planet Saturn, he officially grew up near Birmingham, Alabama. From an early age, Sun Ra loved music that brought folks together: the brassy swagger of big band, the kinetic crackle of swing, and the racy mystery of bebop. As an adult, he found his terrestrial headquarters in the South Side of Chicago. In the meantime, he would develop his disciplined hand, serve jail time as a conscientious objector to World War II, and admire the beautiful complexities of the night sky. While this book is not a comprehensive biography—for that, Youngquist recommends Space Is The Place: The Lives And Times Of Sun Ra (Da Capo Press, 1998) by John F. Szwed—it offers a focused discussion of the musician’s art as it intersects with the events, social currents, cultural obsessions, and political struggles of twentieth-century America.

If his imprisonment marks the birth of his political life, then moving to Chicago commenced his subversive education. Sun Ra was a voracious reader and exacting intellectual. Teetering columns of arcane books filled his apartment, with stacks rising among his spare furniture. Independent study granted him an impressive understanding of forces that have shaped world history. Youngquist expertly charts the musician’s intellectual journey, which brought Sun Ra to found Thmei Research, a secret society that doubled as a publishing house for “black counter-knowledge incommensurable with conventional academic learning.”

Creating a new mythology for disenfranchised black Americans was Sun Ra’s motive for Thmei. His gospel deprioritized Judeo-Christian thought and history in favor of something more ancient. Source material came from the world’s first civilization, Egypt, as well as a number of obscure traditions. Thmei aimed to create “an alternative tradition of greater force and promise gleaned from the combined mystical traditions of Egyptology, theosophy, numerology, and others among the occult,” writes Youngquist. If successful, Thmei could provide the intellectual building blocks to imagine an alternate reality that stands on hope, beauty, and curiosity—and rejects segregation and oppression. “They would forge political resistance,” writes Youngquist of Thmei, “from a slagheap of beliefs deemed irrational, obsolete, or just plain crackpot by Western religion, philosophy, and science.”

With the visionary foundation in place, Sun Ra rolled up his sleeves and started building a house of worship. He “labored tirelessly to improve life on planet Earth, challenging listeners everywhere to heed a simple call to joy.” Sun Ra’s work was playing and conducting music; black lives were at stake in his art. He believed that cultural excellence could be harnessed for social progress, or even social upheaval. “Instead of pursuing a solution through traditional political means,” writes Youngquist, “he turned to culture . . . to imagine and advance an alternative to an oppressive reality.”

Despite exploring Sun Ra’s unique position in civil rights discourse and practice, a sustained engagement with the movement’s other approaches—political, theological, etc.—is missing from A Pure Solar World. Did the Islamic undercurrent of the Black Power movement clash with the pantheistic utopian vision of Sun Ra’s neo-Egypt? Could the Black Church accept ecstasy that rejected Jesus Christ? Questions like these are teased but not explored deeply.

Youngquist does, however, spend plenty of time with Sun Ra in deep space. In the prime of the artist’s career, the Soviet Union successfully launched Sputnik, the first man-made satellite, into orbit. With the celestial spheres demonstrably reachable, imaginations required a new sonic vocabulary. People started to wonder not only what space was like, but what it sounded like.

“Sonically speaking, outer space was a blank slate,” writes Youngquist. “It could sound like anything, from an angelic chorus to a jet engine.” On account of space’s dark intrigue and popular appetite for lounge music, a vapidly smooth genre called “exotica” quickly became the de facto pop cultural sound of space. “Space-age pop,” Youngquist continues, “created its sonic language and then taught listeners how to hear it.” The more artistic alternative to all of this was, of course, Sun Ra, who had been hammering out joyous galactic tunes for nearly two decades.

While the invention of a cultural sonic lexicon for space is not directly related to Sun Ra’s legacy, it’s one of Youngquist’s many pleasant tangents that weaves avant-garde art into a broader cultural tapestry. Another such digression involves iridescent clothing. Sun Ra asked his band to wear outfits that looked entirely out of place on Earth—a potent mix of the pulp science fiction aesthetic, metallic silk, Egyptian iconography, and hot pants. “What place (those clothes force the question) would blacks have in the Space Age as America imagined it?” Youngquist impishly asks. In the book, the effect of these detours is reminiscent of the unexpected discussions of a college seminar.

Many of the artist’s albums feature his esoteric poetry, and Youngquist devotes many pages to the verse. He argues that Sun Ra’s writing is different than any canonical or non-canonical poetry in the Western world; that, on account of its individuality, it deserves more careful attention than it has received; and, finally, that he is probably not the ideal person to take a good stab. Nevertheless, he gives it a go.

One surprising antecedent is British romanticism, notably William Blake. “Like Blake,” Youngquist writes, “Sun Ra constructed an ideological architecture for his poems that enhances their claims. A myth sustains their meanings. And like Blake, he worked as an artist outside the industry that would claim his labor.” That said, there’s a chasm between the lyric verse that would engrave Blake in history and the “equations” found scribbled in Sun Ra’s notebooks. “Whereas conventional Western poetry celebrates particulars and eschews generalizations,” contends Youngquist, “his does just the opposite, dissolving differences into abstract equivalence.”

Fortunately, there’s an uncharacteristically straightforward poem that sums up the Sun Ra aesthetic, whether considering his music, fashion, or poetry. Here’s a snippet:

There is no place for you to go

But the in or the out.

Try the out.

This excerpt conveys Sun Ra’s broader mission to help black Americans see their situation, imagine a fairer world, and then get there. Youngquist, an English professor at the University of Colorado Boulder, does his best to break down the more ethereal aspirations of the writing. On occasions, though, the tone of the book becomes dense with jargon, disconnected, and freely associative—as if the author is hotboxing the Ivory Tower.

In addition to increasing interest in academic circles, Sun Ra boasts his share of musical adherents. As the book’s subtitle suggests, Sun Ra ushered in a worldwide aesthetic called afrofuturism; the style continues to influence mainstream and underground artists. The second black man who came from outer space, George Clinton, brought groove to the third rock with Parliament/Funkadelic, who’ve since passed the baton to genre-fluid rappers like Kendrick Lamar and Childish Gambino. On the cover of a recent album, the hip avant-garde saxophonist Kamasi Washington looks like an Egyptian deity, his zero-gravity afro silhouetted by an enormous moon. One of Sun Ra’s female collaborators, singer June Tyson, paved the way for R&B’s first lady of outer space, Erykah Badu. Prominent players from the band have kept the group together for more than twenty years after Sun Ra departed for his home planet of Saturn. Luckily, Youngquist devotes a whole chapter and an appended discography to help curious readers chart the sonic legacy of afrofuturism.

Sun Ra left Earth a better place than he found it. Youngquist’s deep dive into this art is creative, discursive, and probing. “While the best possible result of reading these pages would be voraciously listening to the vast array of his available recordings,” he writes in the book’s introduction, “they sound better—more purposeful and canny—to ears tuned to social frequencies.” A strictly formal critique of the musician would have generated its own insights, but by pulling the music of Sun Ra into its broader context, Youngquist engages readers in something grander. They—both Sun Ra and Youngquist—give the contentious politics of resistance, the starlit frontiers of imagination, and the contours of hope a fresh look. As Sun Ra would agree, it is only a fresh look at our world that will rocket people to a new and more splendid universe. With A Pure Solar World, we, too, are invited to try the out.

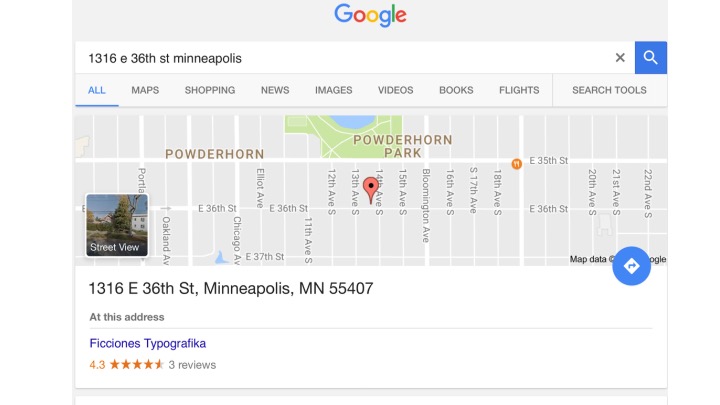

Click here to purchase this book at your local independent bookstore

Eugen Ruge

Eugen Ruge

William Trevor

William Trevor