James Smethurst

James Smethurst

University of Massachusetts Press ($26.95)

by Patrick James Dunagan

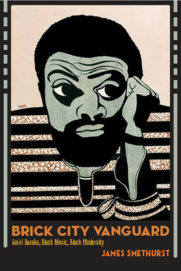

Poet Amiri Baraka belted out revolutionary truth to counter political bullshit, his sharp critique always blistering listener’s ears unlike any other. If it has, at times in the last four years, felt like some stringent poetic analysis has been missing, there is good reason. Baraka passed away just before the disastrously embarrassing turn one New York City (supposed) billionaire took as leader of the Republican Party. He was ever the poet of the people (his people) and the African American core of American culture. With Brick City Vanguard: Amiri Baraka, Black Music, Black Modernity, Baraka scholar James Smethurst cogently charts a clear path through the center of Baraka’s poetics, exploring the intricacies tying his personal development with the larger political as well as social shifts (particularly via Black music) taking place across his lifetime.

With a zeal for Marxist analysis that is never overbearing, Smethurst focuses on an implicit emphasis throughout Baraka’s work. Namely, “the meaning of black music and its role in helping shape an African American people and a black working class that became the heart of the black nation, as well as music as a sort of index or history of the material, psychic, and ideological development of black people.” His first-hand account of how broad a swath of the local Black community turned out for the poet’s memorial in Newark, NJ, offers an intimate look at how Baraka’s commitments in this regard were recognized. Smethurst further demonstrates how elemental this focus proves itself to Baraka’s perspective as a whole, providing a natural grounding for Baraka’s revolutionary principles. As Smethurst accurately depicts, Baraka is ultimately best seen as “a Marxist activist artist, critic, and scholar for the majority of his career,” and that we must remember “he wanted to change the world, not merely study it.” His Black poetics of engagement within/against a white world, no holds barred, remain as alive as ever, not closed to future development, evading any final summation.

Smethurst posits “Revolution, after all, is a process of becoming, not an end in itself,” a statement that mirrors Baraka’s own ever-evolving self-identities, both creative and political. These identities are tracked throughout Smethurst’s study as he traces Baraka’s eventual “evolution as a Marxist artist whose work sounded an analysis of class and nation,” effectively demonstrating “ways that black speech in all its registers can be integrated into poetry.” Baraka continually sounded out this evolution in his work, effectively mining it in order to elevate the concerns of Black communities, especially those of Newark, his birthplace and home both in his early formative years and the later decades of his life.

Going through Baraka’s tremendous output (which, in addition to poems, includes his monumentally foundational study Blues People, liner notes, critical articles, interviews, fiction, plays, and, perhaps most notably for Smethurst, performances/readings), Brick City Vanguard casts fresh light on a vital creator of our time. Smethhurst argues that “Baraka is among the most productive and influential Marxist cultural critics in the history of the United States, if not the world,” a claim of massive weight that feels justly defended here. Smethurst allows, “I see this study as only furthering a discussion” and he has provided abundant evidence pointing to numerous directions ahead—for instance, an unfinished study of Coltrane—for engaging with this remarkable poet and figure. Baraka deserves the attention of this study and the many more that are without doubt yet to come.