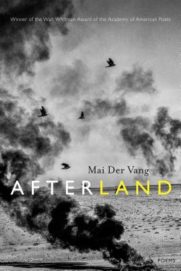

Mai Der Vang

Mai Der Vang

Graywolf Press ($16)

by John Bradley

“Make me the monarch / morphed from suffering” states a section title of Mai Der Vang’s debut book of poetry, Afterland. She’s referring to the suffering of the Hmong due to the Vietnam war, or more specifically the “secret war” in Laos, where many Hmong lived. The author, a Hmong-American, explores in this book the deep emotional turmoil of displacement, exile, recovery of the past, and the difficulty of inventing a new home in the “afterland.”

One poem in particular, “Dear Soldier of the Secret War,” focuses on the devastation of war and the betrayal of the Hmong by their allies, the Americans. The fate of the Hmong soldier left behind with a destroyed village is vividly contrasted with the American who left Laos: “Do you think of the American returning / to the coffee cup, // new linens / in a warm bed, // pulling into the driveway.” Vang does not downplay the horrors of war, as can be seen in this passage of the poem, which describes what happened when the Pathet Lao captured the Hmong soldier and his brother:

It was scalpel that day they captured

you both. They sliced off

and boiled his tongue,forced it down your throat.

That the author feels a responsibility to tell the story of the Hmong can be seen from the first poem in the collection, “Another Heaven”: “I am but atoms / Of old passengers // Bereaved to my cloistered bones.” The unusual choice of the word “cloistered” reflects the poet’s need for solitude as well as for communal connection with those “passengers” who fled the war.

Two poems to the author’s grandparents, “old passengers,” carry the deepest emotion in the book. In “Matriarch,” we see the collision of memory and American culture as it attempts to define what happened in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia. “She points at the television as if she could translate / Rocky, make sense of Rambo,” the poems begins. Perhaps the grandmother can’t translate the films, but the narrator can: “Rambo / Is carnage cloaked in her homeland mud.” There, in this Hollywood war fantasy, can be found the soil of the homeland, and while Rocky and Rambo merge, their eyes can be read; they resemble “dead stars” and speak of “A man omitted.” This the grandmother understands well, the poem tells us.

Much later in the book, in “Your Mountain Lies Down with You,” we hear the author tenderly address her grandfather. “You will see Mount Whitney is as beautiful as Phou Bia,” she promises him. But this beauty, this substitution comes at a cost: “The moon is sharp enough to cut your eat as the one from your village.” The poem closes with these moving lines:

Grandfather, you are not buried in the green mountains of Laos

but here in the Tollhouse hills, earth and heaven to oak gods.Your highlands have come home,

and now you finally sleep.

The use of the word “home” brings comfort, as it means the grandfather’s geography now surrounds him, even as it contains the “oak gods” of another land.

While these poems reveal the emotional undercurrents of Afterland, they don’t convey the author’s bold linguistic play. In a recent interview for the Fairy Tale Review, she offers this advice to poets: “Bend. Risk. Distort. Create rupture.” Advice which she wholeheartedly embraces. Here are some of the lines that beautifully bend, risk, and distort: “The sky sleeps quilted in a militia of stars.” “Ants are spies for the dead.” “The dead cannot be reborn in metal.” “I go to funerals / to keep.” Vang is a skilled practitioner of the declarative sentence, her statements leading us to surprising discoveries. Take the last statement: We expect to hear “weep” but she withholds this, yet the similar sound of “keep” carries with it the emotion of weeping. The sentence doesn’t reveal what she keeps, but the poem suggests that the funeral allows her to keep memories, to keep stories of the past, to keep a culture alive, even as individuals die. Even as the task of carrying on the culture shifts to the next generation.

This stunning collection is not only the debut of a poet with a startlingly original voice; it also reminds the reader how long the legacy of a war lasts. The U.S. left Southeast Asia in 1973, and even now struggles to understand what that failed military engagement means. One sign of this struggle is the new documentary on the Vietnam war by Ken Burns and Lynn Novick, which will be shown this fall. Another sign is our nation’s current questioning of our international role, and specifically our role in Afghanistan. For Mai Der Vang, the cost of war is not about abstractions of policy or theories of power. In “The Spirit Meal,” she writes, “Now the dead come to dine / in my kitchen.” No doubt they will find nourishment in Afterland, as will readers looking for poetry steeped in history.