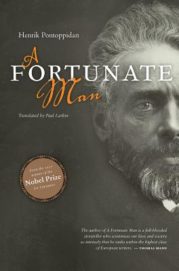

Henrik Pontoppidan

Henrik Pontoppidan

translated by Paul Larkin

Museum Tusculanum Press ($35)

by Poul Houe

This new English translation of a 750-page long Danish novel written more than a century ago is a heavyweight both literally and figuratively. On the volume’s front cover a blurb by Nobel Laureate Thomas Mann reads, “the author of A Fortunate Man is a full-blooded storyteller who scrutinizes our lives and society so intensely that he ranks within the highest class of European writers,” a claim which another cover reminder about Pontoppidan corroborates: “From the 1917 winner of the Nobel Prize for literature.” Add to this that the present translation coincides with two 2018 film adaptations of the book—one for the movie screen, the other for a TV miniseries, both made by Oscar-winning director Bille August—and you are almost compelled to expect a work of art capable of traveling the distance between the late nineteenth and early twenty-first century.

In fact, evidence of the novel’s topicality is not hard to glean. Its eponymous character, Peter Andreas Sidenius, or simply Per, as in its Danish title Lykke-Per (Lucky-Per), is born to rigorously devout Christian parents, the father descending from an endless lineage of Lutheran pastors. But unlike the rest of the vicarage’s large household, Per is driven from an early age by an obstinate zest of life that eventually sparks bold ideas of his own about technical and material matters—much in sync with the modern breakthrough in Nordic culture and society, but completely out of touch with the spiritual norms of the Sidenius home.

Rational and pragmatic, this young disciple of the human god of utilitarian progress is especially intrigued by the energy potential in North Sea waves and Western Winds, and his engineering plans for capturing these otherwise wasted forces of nature for the benefit of the national economy ring like preambles for today’s environmental sustainability agenda. Including his designs for river regulations and a large Jutland freeport, Per’s technological output is precisely as uncompromising as the religious spirituality he was brought up with but now struggles to outmaneuver. Even more than his actual accomplishments, which turn out to be few, this background is what truly throws his striving into relief and makes A Fortunate Man a novel for our time.

More than their prescience, though, it is the failure of Per’s many efforts, and his subsequent life in splendid isolation (as a lowly paid road inspector in his country’s most barren and remote quarters) that deserve the attention of today’s readers. For while the prospects of his ambitions may have stood the test of time, the forces that undercut their currency from the outset, or at least suggested they were premature, remain embedded in our own technology-driven culture and cause today’s humans no less harm than they once caused Per.

Simply put, Lykke-Per, the fortunate man, is also a Skygge-Per, a man of shadows. As Pontoppidan’s lengthy narrative progresses, it reveals in ever so many compelling ways and characteristic details how profoundly indebted to his past this man is, especially when he believes himself to be confronting and resisting his origins most ardently and to be staking out his own path through life. Often others see the link before Per realizes it himself, as when this fellow suitor says to him: “Even if we are not born with chains, we seem to feel an urge to make chains for ourselves as life progresses. We are, and will ever be, a band of slaves. We only ever feel really at home when we are in chains and shackled—what would you say to that now?”

Only gradually, as his forward-moving steps alternate with crushing setbacks, does Per come to acknowledge his susceptibility to the values and attitudes he resents the most. Whether disdaining his provincial father’s religion while seeking the approval of secular urban Jews, or succumbing to feelings of guilt and remorse for his youthful misdeeds, or navigating a spiritual course between religious modes at odds with all of the above, Per increasingly embraces spirituality as a pivotal part of his humanity: not a transcendental spirituality, mind you, but a sense of nature that has affinity to modern technology and science and yet is richer than the outlook of most practitioners of both.

Torn between these opposites at any given time, Per faces shadows of his past while stumbling towards selfhood in the process. When eventually he connects with his father’s faith as an indelible influence upon his own life, it’s the spiritual passion he takes to heart, not the religious doctrine it fueled in his father’s mind. Even Per’s penchant for likeminded characters like Jewish Dr. Nathan is qualified. While admiring Nathan’s intellectual acuity and the eloquence with which he infused the public sphere with modern insights, Per deems his outlook narrowly aesthetic and alien to the natural sciences and modern technology.

Commuting between such diverse sources of inspiration, the fortunate man’s selfhood emerges as a cacophony, a patchwork, and a fluidity: a messy construction of building blocks from near and far but first and foremost a never-ending interaction between the visibly known and the shadows it either casts or represses. It’s Per’s misfortune that such shadows undercut his life, but his fortune that he meets the challenge to come to terms with the predicament. The scene is typically a fairy tale or legend, as when he asks his Jewish girlfriend if she remembers the school book story “of the mountain troll who crawled up through a mole hill so he could live amongst human beings but got terrible fits of sneezing whenever the sun broke through the clouds? Ah, I could tell you a long tale that would explain exactly where that legend comes from!” Per knows! As shadows are both his curse and his blessing, they are what makes him Per, the fortunately unfortunate or unfortunately fortunate man.

Since technology today advances even more rapidly than Per Sidenius’ era of modernity could ever dream of, Pontoppidan’s novelistic lesson about the perilous road to selfhood in a world of our own making could not be more timely. Almost daily we are treated to scary collisions of brazen innovations and the so-called unintended consequences these tend to entail. While progress appears to reign supreme, its shadows are having a ball, and the need to confront the interplay becomes paramount. It’s because fortune and misfortune are often as hard to separate as conjoined twins that a window like Pontoppidan’s on their both vital and deadly nexus is a precious commodity.

Its formal design may seem overly traditional to suit insights into futuristic challenges of this magnitude, but on closer inspection it actually does the challenges justice by bringing their shadowy disruptions to light by way of meticulous disquisitions rather than the style of impulsive tweets. Compositionally, A Fortunate Man, like the standard Bildungsroman, follows its protagonist from the home that shaped him to a world away from there, where his full self can emerge before returning home for confirmation of its independently won identity. For Per, however, the transition never ends, and when, finally, a renewed sense of home does transpire on his own terms, only a version of his homeless experience in no-man’s-land qualifies for the role. The trajectory for his development was traditional, but rather than leading to fulfilment, it led him to drain his life expectations for all that could have compromised his passion to meet them.

Similarly, the novel’s narrative mode and attitude are omniscient and Olympic with movements both between characters and within their minds. Yet while the narrator is the one who knows best, and who tells it best, his puppeteering capacity is not abused to simplify matters unduly, but works to stretch, for better and worse, the human potentials involved to their breaking point. Character depictions and characterizations serve their agents’ most conflicted and contradictory traits, inviting readers to contemplate the ways in which personal centers of gravity are repeatedly split between centripetal and centrifugal forces, or conversely, are stifled in a form of life to be deplored if not avoided.

The disruptions are never far away. Shortly after Per’s personality seems “the first formless template for a coming race of giants, which (as he himself had written) would finally take possession of the world as its rightful rulers and masters—a world which they would then reshape to their own liking and needs,” he goes humbly to bid his father a last farewell. “In ways barely perceptible to him, his decision was linked to other partly diffuse deliberations that had occupied his mind the previous night and, once again, shades of unconquered phantoms had made their disturbing presence felt.”

Again, not only does Pontoppidan’s verbal orchestration deal with authority on the cusp of an existential and national breakthrough that verges on a breakdown; it also offers up an array of painstakingly nuanced individual portrayals and revelations. Alongside this it unfolds, in telling detail, a host of theological and philosophical, political and aesthetic, scientific and technological bones of contention of the kind that defined the cultural and societal scene in Denmark and countries south of its border during the ground-shifting transition from a world of hegemonic national spirituality to one of global innovation and market economic expansion—all turning individual souls more optimistic and more lost than most people realized or had words for.

At book’s end Per Sidenius has died, but only after his tortured search for meaning in life had reached its own dead end. In a journal Per left behind, an admirer learns how he saw this search as “the final aim of our struggle and suffering. Until one day, we are stopped by a voice from deep within us, the voice of a phantom asking: But who are you yourself? From that day forward, no other question matters except this one. From that day, our own self becomes the great Sphinx, whose mystery we must solve.” While space limitations prevent me from quoting most of the journal’s dizzying grappling with the issue, its final words: “I must know! I must know!” suffice to sum up why A Fortunate Man is a demanding read worth the effort.