Jiří Kolář

Jiří Kolář

translated by Ryan Scott

Twisted Spoon Press ($24)

by M. Kasper

“My aim from the outset was to find areas of friction between design and literature.”

—Jiří Kolář

Jiří Kolář (1914-2002) was one of the great collage artists of the 20th century. Like an-other, Kurt Schwitters, he was also a great creative writer, and just as Schwitters’s innovative texts took decades getting translated, Kolář’s writing has been unavailable to us for a long time. Now Twisted Spoon Press from Prague has brought out A User’s Manual, his first book-length literary work in English.

Kolář began as a poet in the early 1940s, publishing in a restless array of styles over the course of two decades: diaristic early on, then documentary, then increasingly experimental, finally concrete and visual. A prominent participant in unofficial art circles, he spent nine months in prison in 1953 for one of his books. Around 1960, he largely abandoned poetry and devoted himself to visual collages, which he’d been making on the side for years.

The collages are extraordinary, among the technique’s most inspiring. Beginning in the 1950s, Kolář (whose name is pronounced a lot like the word “collage”), invented dozens of clever ways to make cut-paper pieces. There’s “chiasmage,” tiny, irregular pieces from printed pages arranged into crazy-quilt textures of gorgeous illegibility; “crumplage,” made with crinkled damp paper; “rollage,” fine art reproductions sliced into strips and reconfigured such that the images wave and stutter; and more. Among his favored collage elements were the above-mentioned printed snippets (in various alphabets, and including musical scores) and art reproductions (Leonardo, Bruegel, Vermeer, Ingres, Magritte) as well as maps, ads, and magazine illustrations of birds, butterflies, and flowers. “Urban pictorial folklore” was how he characterized his raw material. The finished work is polyphonic and unfailingly beautiful, meticulous yet prolific.

Kolář published and exhibited infrequently in Communist Czechoslovakia, as the regime viewed his conceptualism with incomprehension and suspicion. They thought it foreign, though in fact it was mostly homegrown, much influenced by the Czech avant-garde movement of Poetism, a distinctive hybrid of Constructivism and Surrealism with a rich verbo-visual legacy. Perhaps it was shared roots in modernism that enabled Kolář to connect so easily with contemporary Euro-American conceptualists when contacts became possible due to a thaw in East-West relations in the early 1960s. By the middle of that decade, Kolář was exhibiting at Kassel and São Paulo and publishing in avant-garde journals all over Europe. In 1975 and again in 1978, he had solo shows at New York’s Guggenheim Museum.

Kolář’s writing was never as celebrated as his visual art, at least not outside Eastern Europe. Czech isn’t widely read or translated; there were translations into German and French later (Kolář settled in Paris in 1980), but the collages always far outshone them.

Návod k upotřebení (translated here as A User’s Manual) came out in 1969, a year after Russian intervention ended a brief relaxation of repressive government known as the Prague Spring. The book matched fifty-two texts from a series that Kolář had written in 1965 with his Weekly collage sequence from 1967, on facing pages.

In that first edition, the collages, the originals of which are tabloid size and gloriously colorful, were printed in black and white on coated paper and reduced to approximately seven by five inches. Twisted Spoon has done much the same, as befits the near-facsimile this is, except they chose uncoated paper and the new reproductions are consequently grayer and less crisp. They make up somewhat for this uncharacteristic lapse (Twisted Spoon’s production values have been consistently excellent since they started in 1992) by swapping in a half dozen color reproductions, which are bright and clearer.

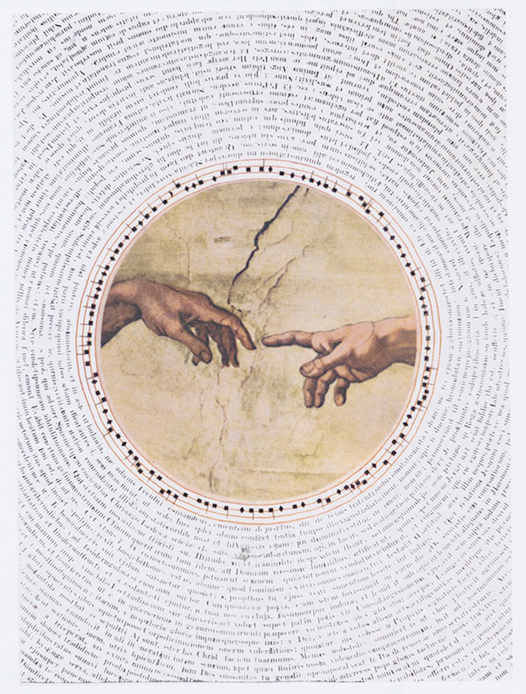

"Homage to a Heart Transplant" Week 49, from A User's Manual by Jiří Kolář

The collages vary in composition from week to week. Some employ only one of Kolář’s methods, while others combine found scraps with small collages made using different processes, often on chiasmage backgrounds, to create what the artist called “narrative poems.” In addition to his typical imagery, Kolář incorporated self-documentation, and newspaper and magazine photos of current events into some pages. Week 8’s collage, entitled “Death of a Scientist,” features a portrait of J. Robert Oppenheimer, who passed away that February. Week 20, “At Loggerheads,” pairs Hebrew and Arabic chiasmages in a commentary on the run-up to the Arab-Israeli War. Week 49 is “Homage to a Heart Transplant,” the world’s first having been per-formed on December 3rd, 1967.

As for the poetry, it’s hardly that, though Kolář called everything he did, including his collages, “poetry.” Most of the fifty-two brief texts here are deadpan, prosy instructions for disrupting normal routines, laid out like verse. As translator Ryan Scott notes in his afterword, “The focus on the seemingly mundane allows for a poetic voice that doesn’t rely on lyricism and emotion. Instead, the voice emerges from the commonplace rendered unexpectedly.” Week 9’s text, entitled “Lips,” reads, “After bath and breakfast / apply lipstick /to make your lips twice as large / and wear it the whole day / until you’ve finished dinner / and gone to bed.” Week 31, “Sonnet,” goes, “Take a novel / you don’t know/slice off the spine/remove the page numbers/and thoroughly jumble the pages / In this disorder / read the book / and in fourteen lines / summarise its contents.”

By his own account, Kolář independently developed these “action poems” in the late 1950s, at the same time that George Brecht initiated what became Fluxus event-scores (directions for performance), which they resemble. In Kolář’s pieces, though, there’s a distinctive playfulness that seems to derive from and also transcend the grim circumstances of their production, and that maybe helps explain how those circumstances were, or could be, borne with some combination of resignation and self-respect. Week 19, “Amnesty,” reads, “From an empty birdcage / hangs / a white flag.”

We’re fortunate to have in English, at last, a real taste of Kolář’s wry, writerly sensibility. Ryan Scott and Twisted Spoon are to be commended for reviving this particular book, a neglected but significant work of Eastern European visual literature.