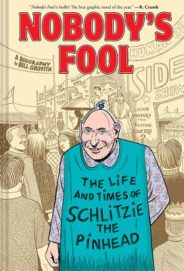

Bill Griffith

Bill Griffith

Abrams Comic Arts ($24.99)

by Christopher Luna

For half a century, cartoonist Bill Griffith has thrilled many and confounded others with his surreal comics featuring an absurdist commentary on the chaotic ebb and flow of pop culture. Griffith’s memoir of his mother’s secret romance with a cartoonist, Invisible Ink (Fantagraphics Books, 2015)—a sweeping, emotional tour de force of autobiographical comic storytelling—was a tough act to follow. However, he has succeeded in doing just that with Nobody’s Fool, the story of the sideshow attraction who inspired Griffith to create his most enduring character, Zippy the Pinhead. Zippy is a jolly microcephalic who wears a muu muu and a topknot and constantly spouts non sequiturs; both his look and his signature behaviors owe a debt to the pinheads found in Tod Browning’s 1932 film Freaks.

Schlitzie worked in sideshows from the 1930s through the 1960s. A succession of caretakers “billed [him] as a female . . . though he was clearly a male,” under a variety of names, including Last of the Aztecs, Julius, the Missing Link, The Monkey Girl, and Last of the Incas. An entire page is dedicated to different versions of Schlitzie’s origin story. As Griffith explains, “the sideshow, after all, is a world where the truth is malleable & exaggeration is rampant.”

We learn about the strange set of coincidences that led Griffith to name his underground comic protagonist Zippy. Zip the What-Is-It? was another sideshow pinhead with whom Schlitzie worked while being handled by Ted Metz in the late 1920s. The pair played violin and piano onstage at Coney Island. After Zip died, “Metz took Schlitzie back to California.” It is easy to trace the connection between Schlitzie’s unique behavior and mannerisms and his fictional counterpart’s non sequiturs and peculiar dietary preferences. Zippy sometimes repeats phrases, reveling in their sound and their randomness. Schlitzie often imitated others. If he liked someone, he would ask if the person was married. When agitated, he repeated the phrase “Y’see?” Schlitzie enjoyed beer, chicken, red hots, and washing the dishes. Zippy has a fondness for ding dongs and taco sauce, and spends time at laundromats watching the clothes spin because he believes that laundry is the fifth dimension.

One of the highlights of the book is Griffith’s behind-the-scenes look at the production and marketing of Tod Browning’s Freaks, a film unlike any other before or since. A dark tale of revenge with an unmistakable statement about the dignity of all human beings, no matter their physical or mental differences, Browning’s follow-up to the success of Dracula starred a bevy of actual sideshow performers; the director had first seen Schlitzie when he himself worked in carnivals. Griffith’s meticulous research allows us to witness Schlitzie’s foray into Hollywood; his wild imagination permits us to experience Schlitzie’s dreams and unconventional thought process.

As in the Zippy comics, Griffith appears as a character in the graphic novel. We meet him as a young artist who was both disturbed and fascinated by what he saw in Browning’s film: “I left the theatre in a half-awake daze, unable to shake the film’s potent images . . . I felt as if I were still inside the movie, living the story, the sideshow freaks refusing to let me go, urging me back into their black & white, 1932 world. None of them were actors . . . which further heightened the feeling I’d been through something very real.” Griffith began painting and drawing Zippy soon after seeing Freaks for the first time in 1963. Zippy made his debut in Real Pulp Comics in 1970 and was eventually syndicated in newspapers around the country.

Although the story has many humorous aspects, Schlitzie and his fellow sideshow attractions lived tough lives filled with mistreatment and humiliation. Griffith has such control over the line that he imbues his characters with the entire range of emotions; we are pulled into their reality so completely that we soon forget that we are looking at a two-dimensional drawing. The skill with which Griffith recreates Schlitzie’s environment works against the tendency to rush through graphic novels. The design is so intricate that the reader is compelled to proceed slowly, getting lost in the details of each panel. Just like Zippy and his many companions, Schlitzie gets under our skin and becomes as real as an old friend.