Interviewed by Elizabeth Fontaine, Evelyn May, and Sarah Degner Riveros

Interviewed by Elizabeth Fontaine, Evelyn May, and Sarah Degner Riveros

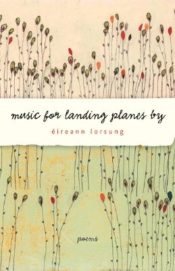

Poet Éireann Lorsung is the author of Music for Landing Planes By (Milkweed Editions, 2007), which was followed by Her Book (Milkweed Editions, 2013) and the chapbook Sweetbriar (Dancing Girl Press, 2013). The recipient of a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship, Lorsung has taught at De Montfort University in the U.K., Ghent University in Belgium, and in the Iowa Summer Writing Workshop. Originally from Minneapolis, Lorsung earned an MFA in Poetry at the University of Minnesota and a PhD in Critical Theory at the University of Nottingham. She currently teaches at the University of Maine–Farmington. In addition to poetry, she is currently working on a novel and a collection of essays.

In the spring of 2019, Lorsung participated in an online interview with Elizabeth Fontaine, Evelyn May, and Sarah Degner Riveros of Augsburg University’s MFA Program. The conversation originated with a discussion of Music for Landing Planes By, but Lorsung’s answers go far beyond that single book.

Question: The title Music for Landing Planes By refers to the 9/11 tragedy, and the book examines human connections and responsibilities. Does community play a role in how you write? For instance, in the endnotes you say you composed the poem “In the Wide World” while traveling by bus, with references to the tangible world (“babies waking up their sleepy parents”) alongside surreal images (“seven fish swim in the air”) and the unexpected (“a homeless man’s teeth”). How does the place of writing affect your craft? Do you have examples of places that inspire you to write, and the types of poems that come to you in those places?

Answer: Here you refer to the method of being-with-others in writing as craft; I think of it as ethics. Writing in public places has been important to me in many ways: as someone who lived as an immigrant for many years, for example, writing in public was a way of making a space in which I belonged within larger spaces where I was often reminded I didn’t, and it was a way of asserting my identity, refusing to assimilate, being myself, reifying my own ways of seeing and knowing and perceiving.

Writing in public also means that I don’t have as much responsibility for “genius.” (I don't really believe in individual genius anyway.) Other people and the places I find myself generally suggest much more interesting things than I would be able to come up with if I were alone.

In practice I don’t always write in public or shared spaces, although these spaces (especially public transit) are really fruitful for me. All of my writing at this point comes from shared spaces—the classroom, the church, the archive—that I enter the same way I enter shared architecture: with questions about what it means for me to be there, reflection on the way power moves, a critical eye to history, and an ongoing effort to be humble, playful, open, and attentive to the spaces, the people who’ve been there (or not) before me, and the meanings I might not have access to or receptors for which are nevertheless in play.

Q: We were drawn to the poem “Gnosis” because of the analogy of a woman being treated like a mannequin. Is this inspired by an actual story? How did the poem change during the process of rewriting and editing?

A: I wrote “Gnosis” in the spring of 2006. At that point I was sewing a lot of clothing, both for myself and to sell. I had a very old dress-form that someone had repaired with duct tape, and I had been slowly taking the tape off and repairing the form.

That spring I spent a little time with a woman my age whom I didn’t know well but who seemed to need a friend. She lived relatively near me in an apartment she shared with her husband. It was always dark and cluttered and a little smelly. I didn’t like to be there. Her husband made me uncomfortable. But I did have the sense she was very lonely and didn’t have anyone to talk to, so I would frequently stop by for a short visit on the way somewhere else or on the way home.

At one point I got a call very late from a number I didn’t know, and it was this woman, very upset. She revealed to me that her husband had been hitting her, she had called the cops, and they’d taken him away. She was distraught. I was twenty-five years old. I had never encountered domestic abuse before and I didn’t know what to do. I don’t remember what I did—probably talked to her for a while.

After a few months, she and her husband moved away and I never heard from her again. Poems have always been one way I theorize what is happening in my life and that is definitely what happened here—I didn’t know how to understand or make sense of this woman’s trauma or my reaction to it, or of her orthodox Catholicism and my own very unorthodox Catholicism.

But it’s not exactly a true story; it’s a poem, the synaptic alchemy of all that was happening at that time, but not a photograph of it. As for the process of editing/rewriting, I honestly can’t recall—it was too long ago, my cells have all changed, and I’m not that person anymore! I know it would have received good and generous feedback from my MFA peers and my professor at that time.

Q: “The Way to Really Love It” and “Exclusion Pregnancy” are remarkable for their balance of sheer beauty and social critique: “Listen to the empty / fields where slate blows / into dust and everything built / glows at night” is such a beautiful image and has a lovely rhythm, and it displays a dark reality of our climate crisis. We see this as well with “you had better / be quick, keep it trimmed, burning—” How do you hold an intentional space for beauty as you write about tough subjects?

A: This is an interesting question. I suppose the simplest answer is that I just don’t see or imagine a world where the beautiful and horrific are not always totally entwined. I have only ever lived in such a world.

The Chernobyl disaster happened when I was five and formed my imagination in an indelible way (the poem “Exclusion Pregnancy” is thinking about the exclusion zone/ nuclear disaster). I remember being excused from reading class in elementary school and allowed to read in the library on my own. I found the area where books about the atomic bomb and the Holocaust were kept and I read everything in the library about those two things.

What is beauty? I guess it’s one kind of thing that makes it hard to look away. Horror is another of those things. The sensation of beauty and the sensation of horror can sometimes share a wall. In the moments you identify in these poems I doubt I was thinking about beauty per se. In “Exclusion Pregnancy” you note the image and rhythm and I suppose the irradiated, glowing landscape is beautiful. Knowing what it is makes it horrific. But this isn’t the landscape; it’s a poem, and poems are aesthetic objects (concerned with what beauty is rather than keeping themselves busy replicating an extant idea of the beautiful). So (this was not conscious; I don’t remember writing this poem; I am reconstructing via analysis rather than depicting something that actually happened), I must have been drawn to something that could encircle and contain the Chernobyl disaster and the long-reaching effects on human health, large-scale and individual.

What is beauty? I guess it’s one kind of thing that makes it hard to look away. Horror is another of those things. The sensation of beauty and the sensation of horror can sometimes share a wall. In the moments you identify in these poems I doubt I was thinking about beauty per se. In “Exclusion Pregnancy” you note the image and rhythm and I suppose the irradiated, glowing landscape is beautiful. Knowing what it is makes it horrific. But this isn’t the landscape; it’s a poem, and poems are aesthetic objects (concerned with what beauty is rather than keeping themselves busy replicating an extant idea of the beautiful). So (this was not conscious; I don’t remember writing this poem; I am reconstructing via analysis rather than depicting something that actually happened), I must have been drawn to something that could encircle and contain the Chernobyl disaster and the long-reaching effects on human health, large-scale and individual.

Form contains and communicates. Those short lines—what I notice about them is how tight they seem and how each of them annotates the syntax, making the line work against the sentence as its own kind of mutation or growth.

The other line you mention is biblical—and I find what I would call resonance with things like that, old things, things that just float in public language. I think some of the beauty comes from that resonance, a feeling of recognition not necessarily to do with belonging to one particular tradition. I am not trying to make my poems “beautiful” although I might have been back when I wrote this book. I just want to reflect how multiple the world is and how simultaneous. People are, are, right now, being tortured, and people are dying ordinary deaths alone or with others, and people are being born, and flowers are starting to bloom, and the stars are out there, and someone has gotten a paper cut, someone is listening to music . . . beauty is just the co-presence of all this. Thought is beauty, and difficult thought is, especially. Thinking about horror is difficult work and we have to do it. If we do it well maybe it makes that wall resonate and what is horrific resembles what is beautiful. I don't know. I feel like this is a question that could be answered by a book that begins by thinking about what beauty is, what intention is, and what poetry can do. What beauty can do? What pain is. A bookshelf.