In the Saturday, September 9, 1989 issue of the Star Tribune, art writer Mary Abbe wrote a column entitled “Lush growth of art blooms in 21 shows.” In it, she previewed a few of the art openings going on that evening, mostly in and around the Warehouse District in downtown Minneapolis. “Nothing demonstrates the unprecedented expansion of the Twin Cities art scene better than the 21 galleries that will premiere new shows tonight,” she wrote. “That’s right, 21.” The art calendar published on the same page offers confirms it with half a broadsheet-sized page packed full of gallery listings, many of them within a five-block radius around 1st Avenue North and 4th Street North. It was an area sometimes known, in a pique of nihilistic ’80s art humor, as NoWare (North Warehouse, get it?), but then as now more generally familiar as the Warehouse District.

If you’re an artist in Minneapolis, you likely know the broad outlines of the Warehouse District story. However, in reading Abbe’s piece, I wondered what it was actually like to be in the area: What are these buildings and spaces like now? How are they used? What do they look like? What do they feel like?

So one recent Friday afternoon, before a Twins home game, I bicycled down to 1st Avenue with a photocopy of the newspaper article, a map, a sketchbook, and a camera to find out for myself—to undertake a Ghost Crawl, two decades later. I picked a game day because I figured people would be out en masse, replicating to some extent the feel of a large weekend gallery crawl.

Here’s some of what I experienced.

Ten of the 21 spaces referred to in Abbe’s article were, at the time, located inside the Wyman Building, located at 400 North 1st Avenue in the Warehouse District, so that seemed like the place to begin. The Wyman was perhaps the flagship space of the Warehouse art scene in the 1980s. The exterior looks much the same as when it was built as a warehouse for dry goods sellers in 1901 (it’s one of the most prominent features of the skyline visible from Target Field—the building with the rooftop water tower). I discovered the inside, however, was completely renovated in the mid-2000s and now appears to be a totally different space than the one that housed those ten galleries in the 1980s.

In the Wyman Building, I start at the top. The seventh floor, where Jon Oulman and Vaughan & Vaughan were located in suites 706 and 712 respectively, is now a single open office space occupied by the advertising agency Colle + McVoy. The elevator opens right into the reception area, where I am instantly regarded with suspicion by the woman at the front desk (probably because I have camera with me). I take a look around at the very polished, wildly well-appointed space, mumble a ridiculous lie about my dad once working there, and turn right around, back into the elevator. On this floor twenty-two years ago, Vaughan & Vaughan exhibited sculptures by noted New York artist Cara Perlman.

On that 1989 weekend, the second floor of the Wyman was occupied byAnderson & Anderson (240), who were showing new work by sculptor Wayne Potratz, and Peter M. David(next door in 236), who were showing prints by nationally known heavy-hitters Dine, Hockney and Motherwell. Now, this floor seems to me the most unchanged by the intervening years. Both 236 and 240 are still present and accounted for: the latter is occupied by the offices of Connect Retail Services (“where the customer meets your brand”), and the former is currently vacant, with drawn wooden slat shades. It’s not hard to imagine a small gallery in either one.

The first floor of the Wyman is now home to two of those Warehouse District nightclubs with stupid one-word names: Aqua and Envy. Other nearby clubs with similarly dumb names: Elixir, Epic, Karma, Drink.

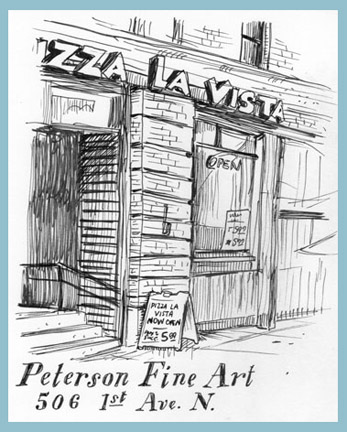

Exiting the Wyman, I head a block south to the one-time site of Peterson Fine Art, at 506 1st Ave. N. That night twenty-some years ago, the gallery featured oil paintings by MCAD alumnus Wayne Ensrud and prints by then-deceased Cubist Max Papart. The space is now the home of Pizza La Vista, a gyros-and-pizza joint catering to the late-night club crowd. Despite an obvious remodel, the interior is easy to envision as a white-wall gallery space, with exposed brick and high ceilings. Two TV sets play a country music satellite station. I buy a Coke and sit at one of the tables. The area feels quite lively, with Twins fans crowded onto the sidewalks, heading for the ballgame.

The Women’s Art Registry of Minnesota at 414 1st Ave. N. was back then opening a group show of Native American artists. The building is one of those gorgeous, red brick warehouses right next to the Wyman. WARM was one of the earliest arts groups to set up shop in the area. WARM is still active as an organization, but the building is now vacant, with the windows papered over. It was obviously the home of a restaurant or bar recently, but I can’t for the life of me recall which one, and all identifying signage has been stripped away. I peek in the window, past the paper, and there are piles of dusty stools and cardboard boxes inside. A sign on the front door reads, “CLOSED UNTIL FURTHER NOTICE.”

Thomson Gallery, located at 321 2nd Ave. N., is noted in the body of Abbe’s article (“‘This year has been one of our busiest ever,’ said owner-director Robert Thomson”), but my calendar doesn’t list an opening that particular evening. Presumably they were open—it was a big night, right? Despite featuring a graphic for an apparently defunct group of crafters and artisans on the window (I checked, but the website listed on the flier is inactive), the windows are papered over, and the space appears to be vacant. It’s in a slight state of disrepair—boarded windows, missing bricks.

The entire block seems deserted.

In fact, I am surprised at how many of these once vibrant art spaces are now vacant. The stadia and nightclubs aside, walking this route is probably closer in some respects to what it must have been like in the early 1980s than in the years immediately following the 1989. I’d fully expected to encounter an advertising agency or sports bar located in every one of these spaces, crouching inside the shell of an identifiable one-time gallery. Really, though, I came across boarded windows, dust, and removed signage as often as I came across thriving boutique agencies.

Perhaps we’re coming around to the end of the cycle that began when those first artists discovered the infrastructure of the Warehouse District was cheap and spacious enough to make for a good home, and which crested when the developers and opportunists came in to take it all over. Maybe the cycle is just waning, putting us back at some point that seems more like a beginning.

Obviously, the Warehouse District will never be what it once was. However, in some of the spaces—the old Thomson space in particular, and the last I saw before heading off—I came across something very striking. The Thomson space seemed abused and cast aside, but it also looked full of promise. It looked exactly like the sort of space an enterprising young gallerist might want to move into.

Rain Taxi Online Edition, Fall 2011 | © Rain Taxi, Inc. 2011