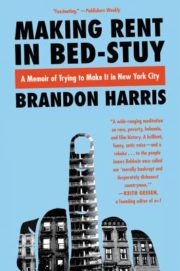

Brandon Harris

Brandon Harris

Amistad ($15.99)

by Joseph Houlihan

Brandon Harris’s Making Rent in Bed-Stuy: A Memoir of Trying to Make it in New York City is symphonic in scope and expression. The memoir, presented in connected film and cultural writings, tells the story of the ambitions and frustrations of a young filmmaker in the decade after his college graduation. A transplant from Cincinnati, Harris experiences the gentrification of the historically black Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood of Brooklyn, and he strives to come to terms with his own ambivalent relationship to the forces responsible for this change.

As Harris seeks to find a voice in a community quickly losing its historical character, Making Rent examines the role of racial difference in the production of culture and social hierarchy. It follows various threads related to the millennial experience, especially looking at the way that gentrification, or the influence of the globalized corporate economy on urban environments, plays out in the lived experience. A paradox emerges, because even as multinational corporations create a sameness across America, difference persists.

Difference cuts many ways. It can create nostalgia for meaningful cultural identities against homogenization, or even hope for the possibility of multicultural communities. Harris moves from Cincinnati to New York City at the beginning of the current development boom, and settles in a neighborhood being rebranded “Clinton Hill.” As a young black man, he speaks bravely about his ambivalence in relation to this process. He moves between the desire to make art that is meaningful to many people and the desire to remain connected to a coherent cultural and historical blackness. All of this is heightened by the titular challenge: making rent.

The book employs a neat framing device; Harris breaks the chapters down by his many itinerant apartments first in Bedford-Stuyvesant, and then later as he’s priced out, farther afield in Queens. Harris is funny and charming as he recounts his social and romantic travails, reminding us that “all we do is for this frightened thing we call love” (as Allen Ginsberg put it in “Wichita Vortex Sutra”). In an interview at The Rumpus, he expands on this idea, saying “empathy is cheap, engagement is more difficult.”

For Harris, engagement presents the possibility of people living together and loving each other. It's important that he describes some of the almost uncanny fears that come in dating white women. He writes about the middle-class experience of code switching, gently mocking lower-class relatives and then later feeling vulnerable and parochial when visiting a girlfriend in an overly WASP-y New England Brahmin setting. And yet he moves through the vulnerability, because engagement is about reaching out and touching other people. One of the most compelling themes in the memoir is that personal values are meaningless if they do not support networks of caring.

This is true of the aesthetics of place, and it's true about people making art. Over the past decade several critically acclaimed white novelists and filmmakers have made works about coming to terms with an adulthood significantly whiter than their childhoods. Another symphonic look at gentrification, Jonathan Lethem's The Fortress of Solitude practically screams, “I lived there in the 1970s!” Conversely, Michael Chabon's Telegraph Avenue imagines a world where people still talk to each other and there is love and compassion in R&B music. It's telling that fewer black voices are asking, “where are all the white people that I loved so much from my childhood?” (America in the age of Trump has a lot of white visibility). But in Making Rent in Bed-Stuy, Harris does capture some of the ambivalence of a person leaving a more multicultural middle-class experience for one of increasing isolation set against the reality of homogenization and downward social mobility.

Hip, and the persistence of cool, is another thread that Harris spins out in the book; he cites early and often some of his heroes and influences, including John Cassavetes, Kathleen Collins, and Bill Gunn. By staking out this territory, he aligns himself with the idea that hip, in the service of a counterculture is worth it. Harris sacrifices stability to grow as a creative voice; he works to support a vital culture that he also seeks to be a part of. And so he reviews small movies, and attends screenings and readings. He works on projects that are not his own, and sends text messages to fellow strivers in earnest solidarity. Even as he does these things, however, things are not quite right. His former best-friend and college roommate becomes a kind of foil in the book, representing the bitter falsehood of the meritocratic promise. The question of making it versus making rent remains unanswered.

Harris came of age in the worst economy since the Great Depression, and of course the black middle class was disproportionately hurt in the 2008 crisis, but Harris approaches this period with wry humor. There’s generosity in his account, and something like straight talk. He’s committed to the artist’s vision, which James Schuyler said is “to be strong / to see things as they are / too fierce and yet not too much.” He strives and he hustles, but even after making it, he has difficulty making rent. He directed a feature film in 2012 called Redlegs, but he was still forced to live on SNAP benefits and write home for money. His parade of part-time jobs and hustles exemplifies the traumatic rupture so many Americans experienced between their perceived sense of self and their lived experience.

In writing a memoir about Bed-Stuy, and the experience of gentrification and corporate homogenization there, Harris is also writing about his own home. In one of the strongest sections of the text, Brandon Harris returns to Cincinnati’s Over-the-Rhine neighborhood:

Gentrification works differently back home than it does in New York. In Cincinnati . . . poor people don’t have organizations of resilience that demand political accountability for their needs. While the black community’s highest strata have collective clout that can shake city hall, their working-class brethren, out in the neighborhoods, don’t . . . The city’s long-blighted and now suddenly urban quarters are gobbled up and renamed.

Like many other cities in the post-industrial moment, Cincinnati’s economy is corporate and largely service oriented. A large community development corporation, Cincinnati Center City Development Corp (3CDC), led much of the development of Over-the-Rhine, “with the largest collection of Italianate architecture in America save Greenwich Village,” into a circus of boutiques, restaurants, and beerhalls.

As a filmmaker, Harris was excited to collaborate with a newly established micro-cinema in Over-the-Rhine, but his excitement was tempered by the organization’s reality. Harris is clear-eyed about this because it represents a big piece of the challenge surrounding the relationship between the avant-garde and politics. Although apparently dedicated to experimental work, the cinema was described as not “the place to complain about the 3CDC.” Short of effecting progressive social realities, the avant-garde is often co-opted into the service of consumerist solipsism. His experience that summer in Cincinnati is further heightened by the police shooting of an unarmed black man, leading to protests and frustration as the City entrenched. It’s a vivid and defining account.

Harris establishes himself as a leading cultural critic in this book, and he is strategic in the filmmakers, musicians, and artists he champions. He reviews an early vision of gentrification in Bed-Stuy, The Landlord by Hal Ashby. He writes about Spike Lee and Da Sweet Blood of Jesus, as well as Nasty Baby by Sebastián Silva. He cites Julie Dash, Chester Himes, Gil Scott-Heron, and Charles Burnett. Through these investigations, he is dedicated to supporting blackness. By choosing Bedford-Stuyvesant, one of the first urban enclaves of free blacks in 19th-century America, Harris is holding up a culture he wants to see persist. This is important, because part of the history of gentrification is based on the changing global economy, but part of it is also the result of explicit racism. Gentrification in the last thirty years mirrors the white flight of the middle century: Slums within urban centers were supported by explicit housing policy, explicitly racial redlining, explicitly racist FHA lending, and explicitly targeted block busting. In this history of Bed-Stuy, Harris tells the biography of an idea worth saving.