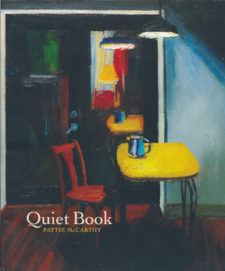

Pattie McCarthy

Pattie McCarthy

Apogee Press ($15.95)

by Jenny Drai

In “genre scenes,” the third and final section of Pattie McCarthy’s new collection of poetry, the speaker tells us to “choose a moment & mark it.” What bookends this instruction is a consideration of individual moments of motherhood, moments that have shaped the parameters of history, language, and Western art. The book takes its name from those handmade volumes made of fabric that contain quiet activities to entertain and instruct young children; in doing so it both considers silence and turns the notion of silence on its head. Motherhood is bustling, even full of white noise that sometimes threatens to consume the self. In “xyz&&,” a series of short pieces containing linked impressions, lists, and micronarratives, McCarthy writes:

in physics, a daughter is a nuclide

formed by the radioactive decay

of another. of course, mother rhymes with

another. but this is just too meta-

& silly & loaded for me. pinion

on the clean fin clear clear wave always at a loss,

we remain open, persons in process.

Here, McCarthy’s use of enjambment and short lines, conversational and pleasantly erudite at once, make a case for the power of insistence in the process of personal evolution. In other words, the line may be over, but the thought continues and joins other thoughts to form the building blocks of personal art. The speaker of this poetry is aware both of depletion and of the possibility that loss (of time? of energy?) is a transformative process that may create an entirely different whole. We are the sum of our present circumstances, this poetry tells us in language that is both spare and evocative.

Circumstance and reflection are considered at length in the ekphrastic poems that make up “genre scenes,” most of which pull the reader in with winding lines that alter pace and make use of repetition. “her I have painted / myself painting myself,” McCarthy writes in “self-portrait, seated.” Constantly, consistently, the poet/mother/speaker writes herself into and away from artistic representations of femininity and motherhood through the ages, considering work by Flemish, Dutch, and French painters of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries as well as more contemporary works by Elźbieta Jablońska and Kate Kern Mundie. In doing so she tethers herself to her own experience of work, creativity (or the lack thereof), and domesticity. In “the listening girl (repetitions exist),” McCarthy evokes a painter who “liked making / paintings of women spinning reading cooking / lacemaking” and writes:

listen in listen listen hush

you’re making so much noise I can’t hear youlet us consider the surface of domestic order

or not let us consider the domestic

or feral pigeon let us pluck it like a chicken

let us empty the wine jug let us be reckless & overheard

In these textured, run-on lines, the speaker both shushes and celebrates the comfortable racket of daily life, suggesting that in the dual navigation of silence and noise, of reception and creation, lies movement and thus survival. Throughout this collection, McCarthy grounds the reader in gestures of love, bemusement, adoration, and interdependence as the poet-mother tests her own boundaries and abilities and tells us, “there is always / another one to be found.” In Quiet Book, the reader finds thrust, brevity, fragmentation, and completion.