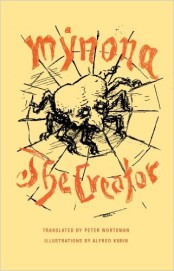

Salomo Friedlaender (Mynona)

Salomo Friedlaender (Mynona)

Translated by Peter Wortsman

Wakefield Press ($13.95)

by Jesse Freedman

At once a philosophical study of dreams and a fabulist rendering of free will, The Creator is a novella unlike any I can remember reading. Its author, the German intellectual Salomo Friedlaender, designated it a “grotesque,” intending it as a magical, almost phantasmagorical meditation on the quest for self-determination. The result is a penetrating, often prescient work of fiction, one that unfolds as a parable might, delivering a clear moral message: embrace the human capacity for imagination, or risk a reality defined by a crippling allegiance to objectivity.

Published in the immediate aftermath of the First World War, and reproduced for the first time in English by Wakefield Press, The Creator takes as its subject the intellectual exchange between the philosophizing figure Gumprecht Weiss and Baron von Böckel, the uncle to Weiss’s love interest, Elvira. Friedlaender, whose work appeared under the pseudonym Mynona (the German word for “anonymous,” spelled backwards), positions the relationship between the men as an extended dialogue focused around the idea of action. He returns repeatedly to this idea, insisting in the dialogue between Weiss and von Böckel that “there can be no creation of something out of nothing.” Humanity, he argues, must engage the will to create; it must act with “absolute freedom.”

This will to create—this ability to activate what Weiss calls “true will”—serves for Friedlaender as the bridge between intellectualism and reality; without it, his characters are reduced to a nightmarish state of inactivity, one in which history slows to a crawl. Like Nietzsche (whose influence is evident throughout the novella), Friedlaender identifies action as core to human potential, going so far as to invoke the idea of the “ubermensch,” the Nietzschean superman. In creativity, too, Friedlaender locates a vital impulse: indeed, both Weiss and von Böckel implore Elvira to create, to exercise an “inner omnipotent strength.” Weiss, in particular, is tempted by the desire to grab this omnipotence, to follow the path of his dreams.

Underlying this impulse is the distinction between “creatures” and “creators,” one Friedlaender constructs using the mirror as his guide: in it, he argues, “creatures” identify reflections of themselves; they approach the mirror objectively, with an eye toward a single truth. By contrast, “creators” locate shades of themselves; they process their image aware of subjectivity, mindful of contrasts lurking below the surface. “Whoever lacks the primordial impulse to tear himself free of the world and inhabit his innermost self,” declares von Böckel, “is only a creature, not a creator.” It is in this way that Friedlaender’s book becomes an homage to subjectivity itself, to a world in which free will navigates a path to its own realization. Without action, as Sartre might have had it, we are nothing.

The Creator is about more, however, than individual will. Friedlaender dedicates a considerable portion of his novella to the subconscious—writing, for instance, of the need for a reality “infused with the ether of the imagined.” In his love for Elvira, Weiss manifests this need most, maintaining that dreams provide “a double face, twice the senses.” It is during a dream sequence, after all, that Weiss first encounters Elvira: later, he learns (or imagines?) that she, too, has dreamed of him, raising the very real question about whether two individuals can dream of one another without first having met. No doubt, Elvira serves as a figment of Weiss’s imagination; and yet, in the surreal universe carved by Friedlaender, where Weiss slips from one reality to the next, Elvira is very much alive. We are the masters of our dreams, the proprietors of their content, Friedlaender argues. This ownership is unwavering.

Ultimately, Friedlaender positions the relationship between Weiss and Elvira in such a way that the two become one: they manifest what he calls the “ideal union,” the space between the “waking world and the world of sleep.” It is here, in this fabulist zone, that Weiss makes his final plea for action, reminding von Böckel that death is more than the lack of action; it is an endless dream state, imagined by the living. And thus as Elvira fades away, Weiss proclaims: “I was pregnant with the world. The objects all around me were nothing but the spawn of my fantasy.” From Weiss, however, there is no apology; to create is to act, and to act is to experience “dream-delight.” This, in the end, is the gift bestowed by this forgotten German master. Life itself must be created.