Kent Johnson

Shearsman Books ($16)

by Murat Nemet-Nejat

just as we come falling into this dreaming: a sky

reflected where we are sailing, and where we reach out

without reaching the beloved who faces us, and who

also is reaching, while we watch the thoughts come,

and watch the thoughts go.—Poem for an Anthology of ‘Poems of the Mind’"

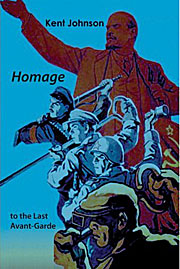

The striking cover of Kent Johnson’s remarkable new book Homage to the Last Avant-Garde nicely conveys its peculiar nature: Lenin aggressively and confidently points his hand to a spot in the future; below him three rows of soldiers point their weapons or industrial tools in the same direction; below them a photographer in a proletarian cap records that yet invisible future event, while to the right a red Soviet flag waves in the style of socialist-realist art. Here is one aspect of the “Last Avant-Garde,” its present correspondent (in Jack Spicer’s sense) being the Iraq War, seen from the Utopian moral angle of a revolutionary ideology. Homage is saturated with horrifying, sublime poems of destruction, such as “The Impropriety of the Hours,” “Baghdad,” and “Lyric Poetry after Auschwitz, or: ‘Get the Hood Back On.’”

The striking cover of Kent Johnson’s remarkable new book Homage to the Last Avant-Garde nicely conveys its peculiar nature: Lenin aggressively and confidently points his hand to a spot in the future; below him three rows of soldiers point their weapons or industrial tools in the same direction; below them a photographer in a proletarian cap records that yet invisible future event, while to the right a red Soviet flag waves in the style of socialist-realist art. Here is one aspect of the “Last Avant-Garde,” its present correspondent (in Jack Spicer’s sense) being the Iraq War, seen from the Utopian moral angle of a revolutionary ideology. Homage is saturated with horrifying, sublime poems of destruction, such as “The Impropriety of the Hours,” “Baghdad,” and “Lyric Poetry after Auschwitz, or: ‘Get the Hood Back On.’”

The military origin of the expression “avant-garde” as it relates to poetry has been amply discussed; what have not been explored are its implications. Homage to the Last Avant-Garde is a meditation, in counterpoints among voices and styles, on the nature of poetic community. Is a poetic community a sentimental utopia, with poets praising and invariably supporting each other, or is it more war-like, involving jealousies, rivalries, the creation of a new text always disturbing, misreading, savagely destroying and enhancing, the surrounding texts? As his reputation as a pit-bull implies, Johnson believes in the dialectic fertility of the latter. “Homage” parallels “After” in Jack Spicer’s After Lorca, Spicer being the “Lenin” in Johnson’s pantheon of American poets. Is “After Lorca” an homage to Lorca or a predatory pursuit? Lorca in the poem resists, resents Spicer’s advances, while Spicer evokes Lorca’s petulant voice (from the echo chamber of the grave), his dissolving body, retrieving fragments or “imagined” translations (which Spicer calls “centaurs”) and a few “fraudulent” letters. The parable which is After Lorca says that what a poet can receive from another poet is a few torn, “ingested”/imagined fragments. Homages are therefore necessarily predatory (militant), doing violence to the passage of time and the alternating subjectivities of two languages or poetic styles.

At the center of Homage are twenty translations, which Johnson calls “traductions,” ranging from the pseudo-literal to the totally imagined, of ancient Greek fragments (or “recently discovered” poems) from his book The Miseries of Poetry. A deep melancholy infuses these magnificent texts—as good as any “traductions” in the English language—pierced as they are with elisions, ruptures caused by the passage of time. They constitute a meditation that says: so few of these ancient poems, still redolent of the dung hill of life, survive; but the surviving fragments are more intense because of their incompleteness. This linguistic magma pulled up from the grave—corresponding to Spicer’s communications with Lorca or from Mars—full of suffering, violence, fury, and a delicate beauty, constitutes the heart, the very essence of Johnson’s poetry. It permeates the war poems—the bombs falling both on Hiroshima and Baghdad—as well as Johnson’s confrontational relationship with the poetic community and his “editorial” relationship with the “translator” of the Greek fragments, Alexandra Papaditsas. In a resonant passage in The Miseries of Poetry, unfortunately omitted from Homage, Johnson describes the life of a poet and its relation to language through the parable of the Cameroonian stink ant, which gets infected by spores of a parasitic fungus during its climb to the tops of the trees in the rain forests. There it dies while the fungus in its body lives on, consuming the nervous system and the remaining soft tissues. Ultimately, “a spikelike protrusion erupts from out of what has been the ant’s head.” The protrusion bursts, the spores fall to the jungle floor and the cycle restarts. In Johnson’s poetics, “the translator” has a similar protrusion in her head, “a large keratinous horn. . .”

The poet is thus host to the parasite of language. The translations are the fruits, the spores, of its life cycle, necessitating the violence of his/her total consumption/consummation. The same passage says, “This large ant [is] one of the very few capable of emitting a cry audible to the human ear.” It is this barely audible cry, of suffering, of burning violence, which makes all the miseries of poetry worth living through.

The debates around Johnson’s poetry have been framed by the Yasusada controversy of Doubled Flowering—which is unfortunate, because it diverts attention away from the utterly serious exploration of the nature of poetry and the poet’s relation to society that Johnson’s work constitutes. While Homage to the Last Avant-Garde is a “selected,” more truly it represents a framing of his total work, where his political poems, translations, and satirical sorties on the American poetic community can be seen within a coherent conceptual framework. I cannot recommend it highly enough to anyone who wants to confront Johnson’s work seriously.

I will end this review by quoting two of Johnson’s “traductions.” The first, “Mission,” embodies the exquisite synthesis between violence and beauty Johnson’s poetry can achieve within the frame of a political poem:

Mission

We decamped from Pylos, barbarian town smack in a boulder field,

and set oar to lovely Asia, making fair Kolophon our base. We gathered

our strength for a fortnight, writing poems and sharpening our swords

by the sea. On the morning the oracle spoke in tongues, the main column

followed the rushing river through the forest, while our unit of ten went upward

and west, along a tributary stream. At a small waterfall we stopped to rest

on some moss, and gazed at our golden helmets and shields in the reflecting pool.

We spoke in low voices of the beauty around us, of the dark, darting trout

and of the strange, haunting songs in the towering trees. We spoke of time,

and friendship, and truth. Then each of us drank deeply from the pool.Aided by the gods, we stormed Smyrna, and burned its profane temples to the ground.

The second, “A God,” can be regarded as a terse summary of this review, or perhaps even as Kent Johnson’s poetic manifesto:

A God

Fear and joy,

love and rage,

sorrow and lust,

all of it molten

and pulsing from

within, forging

the body’s chambered

form, like some incubated

god, writhing himself into being.

[If you need the complete text of the “stink ant” passage, which I am quoting from The Miseries of Poetry it is on page one of Miseries, in a chapter entitled, “Vestibulum [spora tradere]”. Kent Johnson is quoting a passage from a text by Slavoj Zizek.]