Richard Burton

Richard Burton

Prospecta Press ($40)

by Patrick James Dunagan

Meticulously precise, Basil Bunting’s poetry boldly holds forth in its own self-stylized musicality, his phrasing ever spare with little to no readily visible narrative or confessional self-description even when at its most autobiographical. One of the critically anointed early innovators of Modernism, he ranks with the likes of Ezra Pound, T.S. Eliot, Hugh MacDiarmid, William Carlos Williams, Louis Zukofsky, and Lorine Niedecker—all of whom he not only corresponded with and published alongside, but in many instances enjoyed the friendly company of on more than one occasion.

Born in 1900, Bunting’s literary acclaim and financial well being fluctuated widely throughout his lifetime. As a promising young poet in his twenties and thirties, he was right in the mix of things with Pound and W.B. Yeats nearly from the get-go, palling around in Paris and Rapallo. Gaining recognition from peers and financial support from wealthy patrons only to fade away in terms of any literary regard after the 1940s, he subsequently rose again from near obscurity in the 1960s with support and admiration from younger poets such as Tom Pickard, Allen Ginsberg, and Jonathan Williams. Attention to his work has only further waxed and waned in the years since his death in 1985.

There are many gaps in the recorded history of Bunting’s adventurous life, which Bunting himself fancily filled in with tales more fictive than factual. It is not an easy task to unwind such a life. Richard Burton’s is the first full-scale biography of Bunting to undertake the task—both Victoria Forde’s The Poetry of Basil Bunting (Bloodaxe) and Keith Alldritt’s The Poet as Spy: The Life and Wild Times of Basil Bunting (Aurum Press) are nowhere near as comprehensive and often less wary of Bunting’s exaggerated boasts. Burton catches his readers up with Bunting’s far roving movements across the globe throughout the last century. He succeeds in tying together the many diverse strands of Bunting’s complicated, often agonizingly contradictory life.

As a young man during World War I, Bunting went to jail rather than fight, claiming Quaker-Pacifist leanings although he was never a Quaker—though he did have Quaker schooling—only later to volunteer for military service during World War II. In between the wars he had his first round of successes as a poet, along with his first marriage to an American, Marian Gray Culver. This marriage resulted in two daughters, Bourtai and Roubada, along with a son Rustam; their names reflect Bunting’s early interest in the Persian epic poem Shahnameh. Bunting would eventually have close relationships with both his daughters as adults but his son tragically passed away at sixteen while at boarding school due to a polio outbreak. After a successful commanding role with Royal Air Force squadrons in the Mediterranean during World War II he found himself in Persia working on behalf of the British government and married a second time to Sima Alladadian, an Iranian of Turkish descent, resulting in two children, son Thomas Faramaz and daughter Sima-Maria.

Burton notes that Bunting’s time in Persia was a markedly high point in terms of the professional esteem in which he was held: “Bunting’s friendship with some of the most important politicians in the region shows that he had been operating at the highest political level throughout the Middle East, not just in Iran.” Bunting’s full role in the politics of the time in that area of the world remains unknowable. After losing or perhaps forfeiting his official government position and beginning to work on behalf of the British press, he relocated with his new wife back to England as the British colonization of Persia was disrupted and his own life put in peril. After a decade of near poverty and merciless labor, proof-reading for newspapers while his eyesight dwindled, he entered the comparative—if still rather ramshackle and lop-sided—fame of poetry, crisscrossing the Atlantic on reading/teaching tours.

Bunting’s life, as with his poetry, resists any easy reading. Bunting well understood this fact, and biographically he was rather determined to keep things murky. However, he felt confident that a readership would discover his poetry. As Burton quotes him in a television interview aired in 1984: “If you have practically no readers, but those readers were people like Yeats and Pound, and Eliot, and Carlos Williams, well, you’re pretty confident some notice will be taken sooner or later.” Of course, he didn’t attempt to ease the challenge any for readers. Burton reports his distaste for allowing any apparent slack in his work to remain in print: “his total output makes a slim volume. It could have been even slimmer; he wished in later life that he had discarded more.” In addition to his own poems, this holds true for the translations (“over-drafts”) he undertook from various classical languages from Latin to Persian (Farsi).

Burton’s biography-writing style has its awkward moments. He often interjects his personal judgments in a confusing manner, and his take on Bunting comes from a decidedly professional biographer’s position, not literary or poetic in the least. He is also rather provincially British in his outlook concerning possible causes behind the rise and fall of Bunting’s literary stock: “if we have to point to one single obstacle to proper recognition of Bunting’s importance in his lifetime, and his near-disappearance since, his auto-regionalisation is the culprit.” Bunting was a devoted Northumbrian—Northumbria is a county of Britain located just below Scotland on the eastern coast of the island—but few international readers are likely affected one way or another by Bunting’s Northumbrian stance. Its only pertinence to his poetry is the effect upon how his ear heard the pronunciation of poems when read aloud. The best source to follow up for more information on this aspect is the poet himself. For that, Bunting’s splendid lectures on poetry are gathered together in Basil Bunting on Poetry (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999).

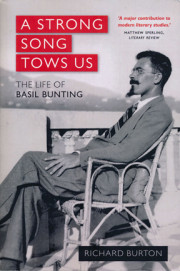

There is no doubt that Burton is devoted to relaying a fair assessment of the poet’s life and work. He announces, “Bunting was a committed Northumbrian and I hope this book will both leave him there and yet liberate him from it.” Yet there is no having two ways about it. Bunting left his work for the world and kept his life for himself. Photographs of Bunting show a gritty glint to his eye and his embittered privacy remains largely undisturbed. It’s rather gratifying that as thorough as Burton’s biography proves itself to be, there’s an endless supply of unknowable quanta he’s unable to bring to further light.