Text and music by Robin Holloway

Illustrated by Ahndraya Parlato

Robin Holloway is an English composer known for works within both modernist and neo-romantic schemata, as well as for his abiding interests in tonality and quotation. An indefatigable creator, his vast output includes operatic, orchestral, and ensemble works; he is also the author of On Music: Essays and Diversions (Claridge Press, 1993) The Times Literary Supplement, The Spectator, Tempo, and Musical Times.

His Opus 70 for violin and orchestra is dedicated to John Ashbery and speaks at a slant to a poem-cycle by Rilke (the title of which translates into English as The Windows), to Ashbery’s poetry, and to Ashbery’s Hudson home, particularly the crystalline windows of the downstairs foyer and the stained-glass windows at the landing of the main staircase. Opus 70 is structured in “windows,” and Holloway suggests that in writing a sort of score for the atmosphere inside Ashbery’s home, he discovered a point of entry into Ashbery’s work and the Rilke cycle which he had previously been denied. Some “windows” had their rough genesis directly under the auspices of their muse: Holloway sketched out a few initial approaches to sections of the work at the piano in Ashbery’s music room.

Holloway’s essay is accompanied by streaming audio files of the complete opening of the concerto, and Windows I through III in full. This music is available courtesy of Boosey & Hawkes. Samples from additional sections may be heard at the Amazon website; another text by the composer on this work is available at the Boosey & Hawkes website.

It’s always a little embarrassing for a composer, dealing with an admired living poet, when the question arises of setting their work to music. (Especially when that poet is so knowledgable, ardent, sensitive a lover of music as John Ashbery!)

I’d had this problem once before with a Great Dead White American, Walt Whitman, leafing in vain through Leaves of Grass for settable sections if not self-contained lyrics. Everything there suggested music, usually with generous magnificence. But nothing actually conduced: too woozy, billowing, voluminous; not enough metre and stanza; the rhythms slack and shapeless rather than specific and exact. Something comparable happened thumbing over Ashbery’s copious output in search of song-possibilities—comparable, but not similar. Where Whitman is gusty, windy, oceanic, declamatory/exclamatory, Ashbery is airy, witty, delicate, and delicious, elusive in avoidance of statement or message, all elision and inexplicitness. The poets have in common, though, a virtually ubiquitous absence of stanza and metre. Those formal props for the composer, while not absolutely indispensible, give him a framework to build on or pull against in the subsuming of words into music that takes place whenever a setting is made. Not that musical possibility is absent in Ashbery’s work! On the contrary, the texture and movement are so musical in themselves that music would have nothing to add, would be duplicative, even redundant.

I really desired, tried, and failed!

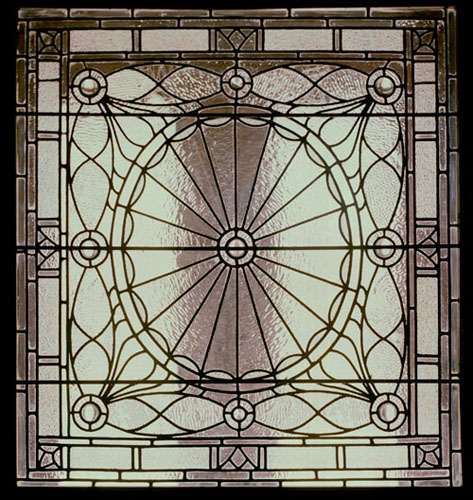

The solution came about obliquely, and from several discrepant sources that converged and merged by pure serendipity. As a guest over a long weekend in the late 1980s, I was enchanted by the house in Hudson, upstate New York; by all its aspects—domestic, literary, social, amical; by the comfort and elegance of the sitting-rooms; the warm, inviting efficiency of kitchen and dining-room; the fully-laden bookstacks in the attic; and, best of all, the ravishing Tiffany-epoch glass, rich in colour and contour when stained and representational, maybe lovelier still when clear, cut with formal geometric patterns. Such sumptuousness, whether cool and symmetrical or lush and lavish, yielded joy by the hour to accompany and support the daily vicissitudes of ordinary living (something more modern décor can never attain), and also struck me as highly germane to its owner’s oeuvre, though I’d find this impossible to explain in academic terms.

Hudson: Pools of lyricism, around which a larger terrain unfolds. Interior front door. Photo by Ahndraya Parlato

My delight in these windows recalled old memories of a late cycle of miniatures by Rilke, from the years when he lived in Switzerland and often wrote in French. Les fénêtres had long fascinated, indeed haunted me, both in themselves and in their vague potential for music. But here too a vocal setting never seemed quite right. I may sound perverse, but I found these tight little poems as unconducive to actual setting as windy Whitman or airy Ashbery. They are too formal, too neat, too precise. You can’t win!

Long ago, I’d asked a French friend to render the Rilke into English prose, as simply as possible, yet retaining depths and complexities beneath the transparent surface. I now turned to these prose versions, setting them to music not for a singer but for solo violin, as core/coeur of a Concerto. Or, rather, as pools of lyricism, around which a larger terrain unfolds. Or, altering the image, as jewels set in the wider surround of the musical forms that hold them together.

Hudson: The medium of reciprocation, always the window between the real and unreal. Main staircase landing, detail. Photo by Ahndraya Parlato

Rilke: for his words (as translated and paraphrased, then not set so much as transubstantiated into wordless melody and texture). Ashbery: not for his words so much as for the glowing, scintillating glass of his windows. Yet an homage to his words is there too, indirectly. It’s an unlikely fusion, but one that yielded a result that I hope speaks and sings for itself.

Behind all this lies a vision of domestic human felicity that is ideal, Platonic even, and utterly French. Never having experienced that felicity, I’ve always dreamed and imagined it—seen it, through windows, from without. It’s the vie de Bohème evoked or depicted over and over chez Renoir, Monet, Degas, Vuillard, Bonnard, Matisse: the flowers on the table with its chequered cloth, carafe, glasses, half-bottle of wine, half loaf; the hall; the stairs; the model/mistress in the bath or emerging, drying herself; the busy arabesque wallpaper; the pinky-orange lamplight; the voluptuous bed. A hymn to the implicit religiousness of domestic intimacy (absolutely lacking moral tags framed above the mantelpiece); felicitous, hedonistic, tenderly erotic; glimpsed from without or experienced within; the medium of reciprocation always the window, its glass opaquely glowing or crystal-clear, between the real and unreal. My associations here are all French, indeed, Parisian. They don’t order thus in England, or Switzerland, or even in Hudson, New York! I’m bold enough to link such a Utopia, via Rilke’s take on it, with some of the principal impulses animating John Ashbery’s verse, in a tribute to him as admiring and heartfelt as it is aslant.