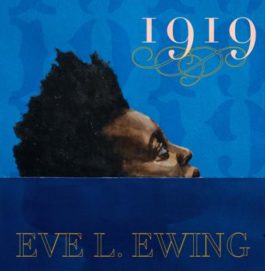

Eve L. Ewing

Eve L. Ewing

Haymarket Books ($16)

by Deborah Bacharach

The 1919 Chicago race riots have marked the city for a century, but few know about them. Eve L. Ewing, a poet and sociologist at the University of Chicago, sets out to change this with her new book. Nearly every poem in 1919 begins with an excerpt from The Negro in Chicago: A Study on Race Relations and a Race Riot, a 1922 city report which attempted to explain the riot. Don’t let the study title make you assume the work dry or inaccessibly academic, however; Ewing has pulled powerful, often terrifying observations from the report and elucidated them with poems full of vibrant voices.

In one excerpt the study refers to the great migration as an exodus. From this thread, Ewing recasts the exodus story as the sharecroppers leaving the South:

And the midwives made an ark of leaves and tar, and put the children therein,

and lay them in the waters. And the people gathered at the bank

and bade them farewell.

and the river carried them far from the cotton, and the kings and their

storehouses of browning blood.

Taking on the tone and rhythms of the Bible gives this historical moment gravitas. Ewing also sometimes writes as characters in the story—a maid, a stockyard worker, a protester, a street car. And sometimes, as in “Sightseers,” she speaks directly to the reader:

and just this once I hope you’ll forgive me

for asking you directly

to forget the lovely water

to forget the charming pillars

because there are children in the tower

there are children in the tower

there are children in the tower

and they are dead already.

In addition to voice, Ewing uses form in the service of meaning. She writes an abecedarian for a teacher from the South who loses his status and must become a stockyard worker in the North; poems about the split between Blacks and Whites are physically split; a poem about barricades is in the form of barricades. She uses found forms like jokes and jump rope rhymes in powerful juxtaposition to the subject matter, too; in “or does it explode,” the epigram tells us it was so hot the city exploded in a riot, and the poem is then in the form of a series of “it was so hot” jokes. There’s nothing funny about the riot or a dream deferred, however (the poem’s title comes from the Langston Hughes poem “What Happens to a Dream Deferred?”) and the contrast creates a powerful tension.

As Ewing contextualizes the poems with photographs and brief history lessons, she combines historical research with a poet’s eye to help us understand the 1919 race riots, an endeavor we should take to heart.