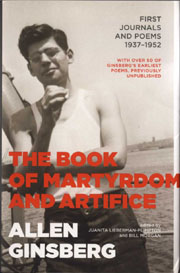

THE BOOK OF MARTYRDOM AND ARTIFICE

First Journals and Poems 1937 - 1952

Allen Ginsberg

Edited by Bill Morgan and Juanita Lieberman-Plimpton

Da Capo Press ($27.50)

HOWL ON TRIAL

The Battle for Free Expression

Edited by Bill Morgan and Nancy J. Peters

City Lights ($14.95)

I CELEBRATE MYSELF

The Somewhat Private Life of Allen Ginsberg

Bill Morgan

Viking ($29.95)

by Christopher Luna

Recently several books have been published which illuminate the life and work of Allen Ginsberg, the best-known poet of the 20th century. The year 2006 was the 50th anniversary of the publication of Ginsberg's "Howl," the work that changed the face of poetry, made the poet famous, and led to the establishment of City Lights as one of the country's most important publishing houses. Ginsberg was out of the country when the censorship trial over "Howl" took place, and according to I Celebrate Myself, Bill Morgan's new biography of the poet, remained slightly detached from the controversy that made the book such a hit. In March 1957 a San Francisco customs agent seized a number of copies of the City Lights paperback Howl and Other Poems "on the grounds that the writing [was] obscene." Both the clerk who sold the book, Shigeyoshi Murao, and the publisher, poet Lawrence Ferlinghetti, were arrested. Judge Clayton Horn, who would later preside over comedian Lenny Bruce's obscenity trial, eventually decided that the book was not obscene.

Typically, the media attention translated into sales, and Howl and Other Poems went on to sell many thousands of copies. Ginsberg did not think that "Howl" was his best work, but he undoubtedly benefited from the fame that it brought him. Ginsberg was more than just an influential poet; he was also an icon of the Beat Generation and the counterculture who had a hand in nearly all of the social changes that took place in America in the 1950s, '60s, and '70s: the antiwar and anti-nuclear movements; the psychedelic revolution; gay rights; free speech; and the spread of Buddhism as a viable system of belief in the West.

Howl on Trial: The Battle for Free Expression, edited by Ginsberg archivist Bill Morgan and City Lights publisher Nancy J. Peters, gathers many of the primary documents related to the case, including the full text of the poem, correspondence, facsimile news accounts, and excerpts from the trial transcripts. The book also includes several essays on the cultural context of the trial and its impact on the culture from Ferlinghetti, Morgan, Peters, and others.

The newspaper accounts and trial transcripts are particularly useful as a way to understand the differences in the attitudes and "community standards" of post-World War II Americans. For example, there are letters to the editor of the San Francisco Chronicle from April 1957 written both by those who support free speech and those who are willing to believe, sight unseen, that Ginsberg's work is obscene.

The correspondence includes a heroic letter to fellow poet John Hollander defending "Howl" and explaining its meaning in great detail. Ginsberg tells Hollander that the key to his method of "keeping a long line still all poetic and not prosy is the concentration and compression of basically imagistic notations into surrealist or cubist phrasing, like hydrogen jukeboxes" and the "elimination of prosy articles and syntactical sawdust." As the letter comes to a close, Ginsberg's frustration with his critics reaches a breaking point: "All this is built like a brick shithouse and anybody can't hear the music . . . [has] got a tin ear, . . . I get sick and tired I read 50 reviews of Howl and not one of them written by anyone with enough technical interests to notice the fucking obvious construction of the poem."

There are also funny letters by Gregory Corso, including a letter to Ferlinghetti in which he warns him against becoming known as a peddler of "dirty books." Corso finally tells Ferlinghetti, "Seriously, I think that you are perhaps the only great publisher in America and will have to suffer for it." Ginsberg remained loyal to Ferlinghetti, steadfastly refusing to "go whoring in NY," despite many offers from larger publishers. He also encouraged Ferlinghetti to publish his friends, convinced that they were the best writers of their generation. In a letter to Ferlinghetti (dated October 10, 1957) written after the decision, Ginsberg states: "If you follow Corso with Kerouac and Burroughs you'll have the most sensational little company in the U.S., I wish you would dig that, anyway; we could all together crash over America in a great wave of beauty. And cash. But do you think you can sell 5,000 more actually? How mad." Today there are nearly 1,000,000 copies of Howl and Other Poems in print.

Reading the trial transcripts, one is astounded by the complete lack of literary knowledge exhibited by many of those involved. Censorship trials are necessarily surreal affairs, as when Deputy District Attorney Ralph McIntosh asks a witness whether the word "snatches" is "relevant to Mr. Ginsberg's literary endeavor." Fortunately, Kenneth Rexroth saves the day, declaring "Howl" to be "the most remarkable single poem, published by a young man since the second war." He correctly labels the poem a "prophetic" piece of literature which is a "denunciation of evil" and "an affirmation of the possibility of being a whole man." Clayton, who had a reputation as a conservative-minded judge, rightfully refused to hear arguments about individual words taken out of context, and found in favor of the defendants.

Lest one think of the trial as a quaint signpost of the past, Morgan concludes the book with an essay about the ongoing battle for free speech. Even today, years after the trial and Ginsberg's acceptance as a literary giant, "the question of 'Howl's' alleged 'indecency' is still unresolved," and the FCC continues to stifle free speech at every turn. "Howl," considered by many to be one of the most important poems of the 20th century, remains a potentially problematic choice for radio broadcasters.

The Book of Martyrdom and Artifice, edited by Morgan and Juanita Lieberman-Plimpton, features Ginsberg's early journals and poems, some from as early as 1937, when the poet was only eleven years old. Sixty-five of the 100 poems included in this volume have never been published before. Young writers may want to crib Ginsberg's reading lists. He also includes many descriptions of his dreams and recalls his thoughts about Carl Solomon, the fellow poet he met in a psychiatric institution and to whom he dedicated "Howl."

Those interested in the work of Beat Generation writers such as Jack Kerouac and William S. Burroughs will treasure these early recollections of the time they spent together when Ginsberg was a student at Columbia University. Ginsberg was a self-described "fledgling" at the time and had not yet come to terms with his homosexuality. It is fascinating to read his thoughts as he stumbles toward adulthood and begins to discover his poetic voice.

Many of the sentiments expressed will be familiar to anyone who has ever been a teenager; often the entries resemble the overheated, melodramatic scribble of any college student. On the other hand, there is no question that the young man whose life is recorded here was destined for greatness; indeed, he seemed to be aware of this himself. In an entry from May 1941, when he was still a student in high school, Ginsberg writes:

I am writing to satisfy my egotism. If some future historian or biographer wants to know what the genius thought and did in his tender years, here it is. I'll be a genius of some kind or other, probably in literature. I really believe it. (Not naively, as whoever reads this is thinking.) I have a fair degree of confidence in myself. Either I'm a genius, I'm egocentric, or I'm slightly schizophrenic. Probably the first two.

The journals include notes for an uncompleted novel that fictionalized the murder of David Kammerer by Lucien Carr, which provides a taste of what it might have been like if Ginsberg had chronicled their lives in the same way that Kerouac did. There are also interesting transcripts of conversations with Carr, often about the purpose of art. Although Carr considered himself a writer, he seldom wrote anything and did not see the point in sharing his "art" with others. Ginsberg felt that what distinguished an artist from the "self-expressive obscurantist" was the "fact that his creation enriches other artists and spurs them to communicate. Thus, accepting the morality of creation and waste, it is wasteful for the artist to chant his poems to the wandering winds or live his art, and not record it. The uncommunicative artist's value is lost to all but himself."

Morgan's I Celebrate Myself: The Somewhat Private Life of Allen Ginsberg benefits from the author's "unlimited access" to the poet's journals. As Ginsberg's archivist and bibliographer, Morgan is the person most familiar with the notebooks in which the poet recorded his thoughts, dreams, and fantasies. Although Ginsberg always allowed scholars access to his journals, in his foreword Morgan admits to being "sometimes . . . egotistical enough to believe that I'm the only person to ever have read everything Allen ever wrote." Ginsberg eventually learned to mine his journals for material; I Celebrate Myself ably demonstrates the relationship between the journals and the final product. This approach also lends itself to a more personal, psychological portrait of the poet than previous biographies.

In addition, throughout the text Morgan has included the page numbers where individual poems can be found in the recently released update of Ginsberg's collected poems, making it possible for scholars and fans to read the poems after having been told how and why they were written.

In an email interview with Rain Taxi, Morgan recalled how he became Ginsberg's archivist: "In the late 1960s I began working on a bibliography of Lawrence Ferlinghetti's work as a college paper. When the professor suggested that they (the University of Pittsburgh Press) publish it, I wrote to Ferlinghetti and asked him a few questions. He invited me out to San Francisco and I began what was to become a ten-year project of compiling a descriptive bibliography of his writing. During the course of that work Lawrence and I became friends and when I needed to see some very scarce publications, he suggested I ask Allen Ginsberg, since his archive was enormous and better than any library's. That led me to meet Allen, since he was generous enough to allow me access to his collection, and when I moved to New York City in the late 1970s I began working on a two-volume bibliography of his work (Greenwood Press) and became his archivist." Eventually Morgan "saw him every day as I worked in his apartment/office and became one of the many members of Ginsberg's cottage industry."

I Celebrate Myself focuses more on Ginsberg's childhood than previous books, and while this is a welcome approach, the chapters that describe the last thirty years of his life seem very short. As Morgan told Rain Taxi, "The biggest challenge was to cram Allen's very full life into one volume. As usual, the publisher was not interested in a two- or three-volume biography, which is really what is needed to cover a life like Ginsberg's. So much had to be left out that the challenge was to limit the coverage, not expand it." According to Morgan, he was not "trying to say that the later years were less important, but the book would have ended up being 900 pages and no one would have been able to pick it up, let alone read it."

One theme of this biography is the daily grind that the poet endured, rarely catching a moment of rest from the time that "Howl" became a hit until his death four decades later. Ginsberg constantly traveled across the globe to read his poetry and contribute his time and energy to various political struggles. Because many of Ginsberg's final years were "spent traveling from reading to reading to conference to workshop, etc.," Morgan "tried to attend to his private life and that made those more public events less important."

Morgan describes Allen Ginsberg as a "true American hero" and a "citizen of the world" whose ideas about democracy were based on his deep understanding of Walt Whitman's life and poetry:

Recurrent themes [in Ginsberg's life story] are his unfulfilled desire to be loved by others and his search for a love of self, which I think he did come close to achieving in the end. His self-love was not wholly narcissistic. Theoretically Allen was able to trace his ability to love directly back to Walt Whitman. . . . Whitman's lesson to Allen was that it is possible to forgive another and love another only after you forgive and love yourself. That was the underlying reason why he felt that Whitman was so important to the American psyche. Whitman had accepted himself and from that flowed an acceptance of all things. Allen believed that Walt Whitman was the first American poet to take action in recognizing his individuality, forgiving and accepting himself, and automatically extending that recognition and acceptance to all other selves.

Ginsberg wrote that it was ego rather than mere "self-expression" that was the "true cause of permanent art."

I Celebrate Myself is also the story of Ginsberg's unending generosity. Early on he rejected the notion of accepting money for personal gain. Much of the money he made from reading poetry went into the Committee on Poetry, a non-profit organization he founded to help other poets in need. Not only was Ginsberg willing to tirelessly promote the work of himself and his friends, but he also supported them financially. Gregory Corso, Herbert Huncke, and Harry Smith were among those who accepted Ginsberg's assistance.

The book is also about the damage that drugs and mental illness can do to people's lives. Morgan suggests that Ginsberg looked the other way when it came to his friends' drug abuse; in the case of his life partner Peter Orlovsky's habit, Ginsberg seemed to be in denial. Some of the saddest moments in the book depict Orlovsky's decline into madness, and the difficulty that Ginsberg had letting go, however necessary their split may have been.

Allen Ginsberg withheld very few of the personal details of his life from the public. In fact, he made a practice of being candid, famously stating, "Candor ends paranoia." Asked to recount any surprises to come from his research, Morgan points to his discovery "that when Allen was only 21 years old, the doctors asked him to sign the release papers allowing them to perform a prefrontal lobotomy on his mother, Naomi. (His father and mother were divorced by this time, so Allen was Naomi's closest living relative). He put his faith in the doctors and signed their request form, which I'm certain he regretted for the rest of her life, for in fact the operation did not help her or stop her suffering." Ginsberg's childhood experiences dealing with his mother's illness, and his guilt over her treatment and death, became the subject of what many consider his greatest poem, "Kaddish."

Ginsberg was also very generous with his many admirers. He had a way of focusing in on the person he was conversing with, no matter what chaos may have been going on around him. In the book, Morgan describes an encounter that Ginsberg had with the photographer Edward Weston in 1956 after which he "resolved to be equally generous with his time with young fans in the future." In Morgan's opinion, "More than anything else, I think he was unique because he took the time to be interested in everyone he ever met." I found this to be true of the few encounters I had with the poet, including a brief conversation during the tribute to Ginsberg which was part of the 20th anniversary of the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics at Naropa University, the Buddhist college in Boulder, Colorado, that Ginsberg founded with Anne Waldman and Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche in 1974. Ginsberg made me feel as if I was the only person there, despite the throngs of friends and fans standing all around us waiting for their turn. I count myself among the many that were fortunate enough to have shared a moment or two with the poet who changed my life.

Morgan's biography is an important addition to the literature on Ginsberg; here's hoping that someone will write that multi-volume version of his life story someday.

Click here to purchase The Book of Martyrdom and Artifice at your local independent bookstore

Click here to buy The Book of Martyrdom and Artifice from Powells.com

Click here to purchase Howl on Trial at your local independent bookstore

Click here to buy Howl on Trial from Powells.com

Click here to purchase I Celebrate Myself at your local independent bookstore

Click here to buy I Celebrate Myself from Powells.com

Rain Taxi Online Edition, Winter 2006-2007 | © Rain Taxi, Inc. 2006-2007