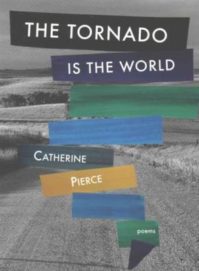

Catherine Pierce

Catherine Pierce

Saturnalia ($16)

by Allison Campbell

As way of introduction to Catherine Pierce’s third book, The Tornado is the World, you might watch the Motion Poem “The Mother Warns the Tornado.” The short film accomplishes what good trailers are meant to accomplish; you are left wanting more. The poem confesses, “I am a greedy son of a bitch, and there / I know we are kin.” In watching the eerie images unfold to form Pierce’s narrative—leaves fight in ominous wind, a floral-print mattress covers a claw-footed tub—and hearing the poet’s hollowed-out voice say, “I know I’ve already had more than I deserve,” readers are bound to feel greedy, to want the rest of the poems this voice and imagination have created.

In “True Story” Pierce writes, “no told story is ever true enough.” Her syntax creates a new noun, “told story,” an alternative to story, raising the question whether or not a story is, indeed, a story before it is told. Whether it is or not, in The Tornado is the World Pierce is set on exaggerating her way to reality, and I mean this in the best sense of exaggeration. In poem after poem, Pierce raises the stakes on what might otherwise be the emotionally mundane; voices of the tourist, teenage girl, and checkout clerk vacillate between cliché, comic, and sagacious. “I Used to Be Able to Listen to Sad Songs,” for example, begins with a simple and calm enough first line, but rapidly amps up after the first line break:

but that was before they started strutting

around with rocks in their fists, started

kicking the backs of my knees so that I

crumpled right there on the asphalt,

their faces streaming tears all the while.

That was before they started showing me

the switch blades in their boots. Before

the twisted arms and sucker punches.

Other addresses are more subdued, less hyperkinetic. “The Dog Greets the Tornado” has a narrative voice that calls to mind the sardonic narrator of Natsume Sōseki’s classic Japanese novel, I Am a Cat—while the cat says, “The truth may simply be that human society is no more than a massing of lunatics,” Pierce’s dog is more accepting:

Hello one-not-like-me. Hello

to your great tail. You are larger

than the truck that takes me

to the woods and back. You are larger

than the house I sometimes go in.

I see you coming close. I am blown

back on myself. My teeth buzz.Today I caught a squirrel. Today

I dug a patch of earth bare and slept

for a while. It was a good day.You are so large. The man is inside

the house. I feel my haunches needling up.And now the brown trees are below me.

The house is below me. The man

is below me. I am part of the sky.

I hear you howling. You must

have learned that from me.

The book contains many poems with tornado as theme or persona—poems that fluctuate between the strikingly grim and potently humorous—but Pierce’s work in The Tornado is the World is not limited by the theme. In “The Unabashed Tourist Brings Her Lover to the French Quarter,” she writes, “In this place / you can buy me a hurricane, and we can / stroll all night with storms in our hands.” The contrast between common consumption and catastrophe in the word “hurricane” creates a type of social, moral, and environmental whiplash. Pierce frequently pulls the rug-out-from under this way. In so doing, her poems remind readers that no one is immune to disaster. But the writing also highlights that forgetting and remembering our proximity to calamity is key to the beauty and absurdity of what it means to be utterly, vulnerably human.