Bill Cotter

Bill Cotter

McSweeney's ($25)

by Jenn Mar

Family history guides Bill Cotter's tragicomic The Parallel Apartments, an infectious, off-kilter novel that might best be described as the aftermath of a domestic drama that has been eaten alive by outsider genres. The Parallel Apartments follows Justine Moppett, a 34-year-old pregnant woman, as she flees an abusive relationship in New York to uncover her birthright in Austin. The novel spans three generations of Justine's dubious family history and sprawls into other storylines that careen toward a terrifically disastrous conclusion.

Cotter fearlessly brings on stage a sizable cast of over-a-dozen misfits, a number of whom are inconsequential to the plot, but whose appearance contributes to the colossal, offbeat production that is The Parallel Apartments' twisted parade. Cotter's weirder character portraits include Murphy Lee Crockett, a pathetically clumsy young man whose fear of blood prevents him from fulfilling his calling as a serial killer; Marcia Brodsky, whose growing credit-card debt inspires her to become a raunchy entrepreneur in the robotic sex industry; Marcia's prostituting android Rance; and April Carole, a deranged soap-opera singer whose ticking biological clock sends her on a sexual rampage.

For this 500-page novel, Cotter achieves a nearly flawless symphonic performance that masterfully arranges multiple storylines and switchback timeframes. There is a surprising amount of action in every chapter and plenty of red herrings and plot twists to keep readers guessing. The book's climax is the ultimate end point from which the chaos of these dozen-or-so-characters' interfering lives can be seen as intelligible, albeit from a downright sinister perspective.

At times, The Parallel Apartments feels like a soap opera rewritten by a literary prose stylist in thrall to a menacing, drug-induced vision of a gruesome world order. This is because Cotter subverts literary traditions with conventions from the thriller/horror arsenal. It's no coincidence that Justine watches marathons of Law and Order: Special Victims Unit, a television series about psychopaths and their sexual-based offenses. Like the television show, The Parallel Apartments features psychopaths, ultra-heightened suspense, and titillating scenes that are inextricably paired with terror and gore. The beams of Cotter's novel, however, flex and groan under the strain of its more graphic depictions. The lurid content is sometimes meant to be tongue-in-cheek and other times meant to inspire horror; squeamish readers may find the passages excruciating. In one chapter, we're made to endure the cringe-inducing details of a geriatric's murder, a process involving electroshock therapy and an intricate contraption of tubes and a blood-pumping valve. While these scenes arguably achieve the jaw-dropping pyrotechnics of a literary spectacle, one comes to suspect that the sado-erotic violence serves less for character development than for entertainment.

McSweeney's has been marketing Bill Cotter as a Texan Gabriel Garcia Marquez, and this comparison has leapt into early reviews of The Parallel Apartments. Indeed, Cotter's prose shares the same stylistic exuberance, the echoing salience and delicately phrased, potty-mouth witticisms of Garcia Marquez's writing. Consider the drama and symmetry of this whopping sentence:

After ejaculating in her mouth, Franklin, Justine's first and last customer, gave her ten dollars, took her by the hand, brought her upstairs to Forty-Second Street, hailed them a cab, lectured her on insisting on payment before performing the next time she fellated a stranger, and brought her home to his apartment in Hell's Kitchen, a not-unpleasant one-bedroom, where she spent the next half of her life tolerating a triple-bogey boyfriend, denying him a child, avoiding his rampant, bar-sinister penis, and growing to like him less and less, while at the same time he grew less and less likable, more aggressive, meaner, more controlling, more Franklin.

Besides their shared love of the baroque sentence, there are other similarities between Cotter and the late Nobel laureate. Like Garcia Marquez, Cotter juggles multiple storylines and shifting perspectives within a marvelously disobedient structure, one that evokes the tangled mess of old Christmas tree lights in storage—surely, one of the more highly technical feats of storytelling. Yet Cotter's novel lacks the fraught poignancy, the graceful state of sustained incomprehension that Garcia Marquez so famously defined in his depictions of life and death, rebirth and suffering, and the menace of history repeating itself.

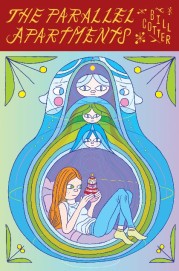

Cotter’s novel is undoubtedly a tour-de-force. Cotter has mastered, from the lowest to highest orders, the elements of fiction; his sentences are as grand as the sweeping architectural details of his book's structure. These features alone make it more than worthy of the reader's investment. But perhaps the one thing missing from The Parallel Apartments is that it lacks a coherent ethos, or simply a moral one. Cotter's novel is committed to an aesthetic of storytelling that is immediately pleasurable, but at the expense of a more lastingly gratifying metaphysical order. After all, The Parallel Apartments is a postmodern representation of an absurd, malfunctioning universe to which all human responses are inadequate. His characters struggle with problems that cannot be resolved, and the novel's recurring motif of the matryoshka doll will come to symbolize not only the nesting histories of a five-generation matriarchy, but the logical exhaustion of their tragicomic existence.