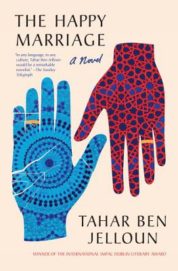

Tahar Ben Jelloun

Tahar Ben Jelloun

Translated by André Naffis-Sahely

Melville House ($25.95)

by Garry Craig Powell

The irony of the title of Tahar Ben Jelloun’s new novel, The Happy Marriage, probably goes without saying. The novel is a study in the unravelling of a marriage in the spirit of Ingmar Bergman, whose Scenes from a Marriage is frequently referenced in the chapter epigraphs, which are all from arthouse cinema. These set the tone of the characters’ lives, which are anything but those of conservative Arabs. The main character, a famous Moroccan painter living in France, knows real-life celebrities like Leo Ferré, Alain Delon, Francois Mitterand, and Antonio Tabucchi—as Ben Jelloun, himself a renowned Moroccan novelist living in Paris, probably does. The painter is obsessed with cinema, indeed far more than with painting, and leads a secular, sophisticated, and sexually promiscuous life. The narrative opens soon after the painter has a stroke following an assault by his wife, who has thrown a laptop and a bronze paperweight at his face; this prompts him to take stock of their twenty-year marriage.

The first three-quarters of the novel is a transcript of a text called “The Man Who Loved Women Too Much,” a third-person account of the disintegration of the marriage from his point of view, written with the help of a friend. According to this version of events, his unnamed wife is fourteen years younger, hails from the Atlas Mountains, and is a Berber, unlike him (he is an upper-class Arab from Fez), but she has lived in France, worked as a model, and has a patina of sophistication—enough, apparently, for Alain Delon to promise her film work. Nevertheless, although the painter is in love with her at the start, tensions arise between their families because of the social disparities: her family are hicks, and his mother complains that she is “not even white.” An aunt of his berates her: “Why can’t you speak Arabic properly and what’s up with that accent?”

In the painter’s view, his wife is a virago who employs peasant au pairs, cancels a symposium he’s due to attend in Berlin, and fires his loyal factotum—all without consulting him, out of jealousy. She is under the spell of Lalla, a fraudulent mystic, witch, and feminist. After the stroke, she becomes jealous of Imane, the tender young Moroccan physiotherapist who treats him, and fires her, to his fury. Dramatic as some of these events could be, they are mostly “told” rather than “shown,” and the language is flat and even clichéd at times (the painter is “white as a sheet”), so much of the potential vividness of the scenes is lost.

As with much Arab storytelling, the narrative here is digressive sometimes entertainingly so, as when Imane tells the painter a surreal “love story” about the woman who ate her husband in order to control him; but on occasion the digressions are clumsy, as in chapter fifteen, in which the painter lists his memories of past lovers, and chapter sixteen, an even more random collection of reminiscences. The reader half-expects a romance to develop between Imane and the painter, who is clearly in love with her, and yet the final crisis has little to do with this, but comes when he informs his wife that he wants a divorce.

This crisis is not resolved in the novel-within-the-novel but in the final part of the book, a first-person narrative called “My Version of Events,” in which his wife, whom we learn is named Amina, responds to the “The Man Who Loved Women Too Much” (which she snarkily points out is an allusion to Truffaut’s The Man Who Loved Women, yet another cinematic reference.) This narrative manoeuvre is not wholly successful because we don’t discover for whom she has written her response, or for that matter why the painter and his friend have put together the first manuscript.

Amina does corroborate some things we have learned from the painter: she admits they were deeply in love in the beginning, confesses she is “nasty” and violent, and spends more time with Lalla than with her husband and children (who are so shadowy that they never emerge as characters). She confesses that her own family always come first, and that she can be cruel. She taunts him with a text: “You don’t satisfy me either sexually or financially.” On the other hand, we learn that her husband is a cheapskate—assuming we can believe her—who always flies Business Class, while making his wife and children travel in Economy. He is, in her words, “an ayatollah in western clothes.” She divulges that she has “read many French novels and identified with the petty bourgeois characters from the provinces” and convinced herself that she too has an intense “an intense inner life.” However, she is no self-destructive Emma Bovary; her plan is to not to destroy her husband, but to make the invalid wholly dependent upon her. “He’s mine now and I can do what I like with him,” Amina declares chillingly near the end.

One might see The Happy Marriage as an expression of Arab male anxiety about the increasing independence and assertiveness of women. Interesting as that is, for an author who has won the Prix Goncourt and numerous other awards, one hopes for a greater mellifluousness of style as well as substance.