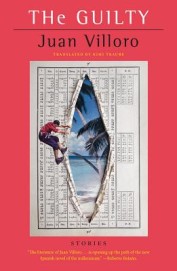

Juan Villoro

Juan Villoro

Translated by Kim Traube

George Braziller, Inc. ($15.95)

by Peter Grandbois

Juan Villoro has been a well respected and widely read writer in Latin America and Spain for many years, publishing five novels and eight short story collections along with numerous children’s books and a steady output of articles on sports and music for Mexico’s leading papers. Sadly, he has remained unknown in the U.S., at least until now. In large part due to winning the prestigious Herralde Prize for his novel El testigo, the independent publisher George Braziller, Inc. has agreed to publish two of his works beginning with Villoro’s hilarious and wildly absurd short story collection, The Guilty.

With famed serious writers like Juan Rulfo and Carlos Fuentes, Mexican literature has not exactly been known for its humor, which is why Villoro’s work is so refreshing. That’s not to say Villoro doesn’t owe a debt to his literary forebears. Rulfo’s lyricism and Fuentes’ formal experimentation are on display in nearly every story in the collection. However, like any great writer, Villoro at once acknowledges his country’s literary history and extends it, moving into David Lynchian layers of unreality. Take for example the longest story in the collection, “Amigos Mexicanos,” where we follow a gluten-free American journalist named Katzenberg as he searches for an “authentic Mexican experience,” only to find it in a fictional kidnapping orchestrated by a scriptwriter looking to create a little publicity. Or take the story “Holding Pattern,” in which the main character spends his time waiting for a plane that may or may not ever arrive to take him to see his girlfriend. As he waits, he reads a book written by his girlfriend’s former lover, only to realize the book may be determining his reality.

Then there’s the disillusioned mariachi from “Mariachi,” a man whose life seems to be unraveling with each new success. “That night I dreamed I was driving a Ferrari, running over sombreros until they were nice and flat.” He yearns to escape the world of mariachis, but he is trapped by the very clichés that define that world. The climax occurs when he stars in a movie in which the special effects are noteworthy: “There was a scene where a biker came close to touching my penis and a colossal member appeared onscreen, impressively erect.” He seeks help from the movie’s producer only to find that everything in his career, including the meeting, has been carefully manipulated. In Villoro’s stories, sincerity is not possible. Everything is a manipulation. Each “reality” we think we inhabit is only another surface designed by a marketing team. As one character says in “Amigos Mexicanos”: “We live in a world of ghosts: copies of copies, everything is pirated.”

What makes this postmodern romp different from so many others is Villoro’s deadpan wit, captured in the eminently readable translation by Kim Traube: “It was the iguana’s fault. We stopped in the desert next to one of those men who spend their whole lives squatting, holding three iguanas by the tail. The man we called El Tomate, 'the Tomato,' inspected the merchandise as if he knew something about green animals.” Any translation is only as good as its translator, and this opening from “Mayan Dusk” beautifully conveys the humor living in the concise phrasing and matter-of-fact tone of Villoro’s prose.

The U.S. lags behind the rest of the world in publishing translations, and if this book is any indication of what we’re missing, it’s a real shame. Villoro made me believe in the power of postmodernism to reflect back the multiple surfaces of our own highly constructed and often fictional lives. To do so while making the reader laugh out loud is no small feat.