photo by Autumn Pingel

Interviewed by William Stobb

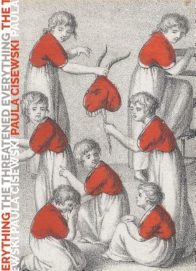

Poet, memoirist, arts activist, and tarot enthusiast, Paula Cisewski’s been turning the Queen of Cups upright for the Twin Cities literary scene since the 1990s. The author of four poetry collections and several chapbooks including a lyric prose memoir, Cisewski has curated a number of reading series, mentors poets and writers of all ages and interests, and sees the work of community-building as the heart and soul of the literary life. In 2017, her two most recent collections hit the shelves, Quitter (Diode Editions, $18) and The Threatened Everything (Burnside Review, $13). I caught up with Cisewski on a blustery spring afternoon in northeast Minneapolis to talk about rage and joy and laughter in apocalyptical poetics.

William Stobb: You’re experiencing something right now that must be a rare moment for any writer, having two books out at the same time. What’s that like?

Paula Cisewski: It’s an embarrassment of riches, and I know what that saying feels like now: like a stroke of luck that may make it appear I’m more productive than I am. The Threatened Everything was accepted in 2014 and Quitter won the Diode prize in 2016. The set of circumstances that caused them to come out simultaneously (and seven years after my last poetry collection)—different lengths of time for each manuscript to find its home with a publisher and then the different production times for each—felt almost unbelievable. The boxes with my author copies of both books actually arrived on my front porch on the same day—I’ll probably never get over that.

WS: That’s wild.

PC: It’s extremely lucky, and I only hope to be a good enough shepherd of them both into the world. They’re very different projects: I was nearly dead when writing The Threatened Everything and the poems rail against feeling trapped there. Quitter spirals forward from that place, however lost for any solution (which is its partial resolution).

And it’s also been interesting hearing from a few people who’ve given me personal feedback: there’s almost always a strong preference for one book over the other, split about 50/50 in favor of each.

WS: I’m one of those people, I know. I like Quitter, but I fell head-over-heels in love with The Threatened Everything, right from the opening poem, “The Apocalypse Award Goes To—.” It strikes me as a great introduction to a lot of things that the book does in terms of themes and tones and voice, and it introduces this interesting idea that we’re living inside of an apocalypse, that the apocalypse is happening and we are in it. That resonates with me in terms of growing up in the Cold War era, and growing up as a Christian and a sci-fi fan—we get ideas of the apocalypse as something that’s going to happen on a given day, and then maybe there’ll be something after that, kind of like Mad Max or The Walking Dead, you know? But maybe it’s more realistic to look at what’s happening in the world right now as an apocalypse. Is that an artistic concept that the poem is built on, or is that a lived experience for you? Do you feel like we’re living in an apocalypse?

WS: I’m one of those people, I know. I like Quitter, but I fell head-over-heels in love with The Threatened Everything, right from the opening poem, “The Apocalypse Award Goes To—.” It strikes me as a great introduction to a lot of things that the book does in terms of themes and tones and voice, and it introduces this interesting idea that we’re living inside of an apocalypse, that the apocalypse is happening and we are in it. That resonates with me in terms of growing up in the Cold War era, and growing up as a Christian and a sci-fi fan—we get ideas of the apocalypse as something that’s going to happen on a given day, and then maybe there’ll be something after that, kind of like Mad Max or The Walking Dead, you know? But maybe it’s more realistic to look at what’s happening in the world right now as an apocalypse. Is that an artistic concept that the poem is built on, or is that a lived experience for you? Do you feel like we’re living in an apocalypse?

PC: First, thank you for spending time with the books and caring enough to have a preference! I don’t know about the apocalypse. I think about self-fulfilling prophecy and it almost seems—well, it doesn’t almost seem, there are people actively praying for the End Times right now, right? As salvation from perceived evil or as a relief from suffering or as a kind of cause and effect that makes sense. Because uncertainty is worse? Plus we as a species have increased our capacity for destruction in ways that seem inhuman to me. So much is terrible, looming indefinitely, and yet there have to be ways that we can know and engage with what is actually here, not what we hope or fear will be. Poetry is one way to connect rather than to succumb to despair or distraction or disinterest. I’m not sure if that exactly answers your question, but those are some of the concerns of both books, I think.

WS: The epigraph to The Threatened Everything from Virginia Woolf is telling: “The beauty of the world which is so soon to perish has two edges, one of laughter, one of anguish, cutting the heart, asunder.” Your poems work through painful situations with a very light touch and with a lot of tonal range—I find a lot of laughter and brightness of wit and brightness of observation in the poems. Do you recognize that in the poems? How can a poem be funny and also tragic? What do you think about tonal diversity in that way in your work?

WS: The epigraph to The Threatened Everything from Virginia Woolf is telling: “The beauty of the world which is so soon to perish has two edges, one of laughter, one of anguish, cutting the heart, asunder.” Your poems work through painful situations with a very light touch and with a lot of tonal range—I find a lot of laughter and brightness of wit and brightness of observation in the poems. Do you recognize that in the poems? How can a poem be funny and also tragic? What do you think about tonal diversity in that way in your work?

PC: I suppose laughter is elemental to who I am—both as a dumbfounded response to frequent wonder and as a coping mechanism—so humor does show up in my work. The final section in The Threatened Everything is called “The Laughing Club,” because I spent a lot of time thinking about laughter: when it expresses joy, when it connects us, and when it’s derisive or divisive. As one part of my research, my husband and I attended a laughing club, which is a real kind of yoga that involves some willingness to be physically vulnerable in public and to make a lot of eye contact with strangers. I’m an introvert, and my husband said he kept his eye on me the whole time in case I bolted and he needed to follow me out.

Ultimately, almost nothing is just one thing. There’s hopelessness; there’s also hope. The “Empty Next Syndrome” poems in The Threatened Everything, for example, explore the altered identity of a parent whose child is becoming/has become an adult. The pain and joy of that experience quite literally shattered me. But it wasn’t about me, was it? It was about my son, who has grown into a loving, generous person in the world. Plus, I’m now grateful to have had the chance to reassemble myself.

WS: I’d love to hear you talk a little bit about the laughter epidemic in Tanganyika and how you encountered that history, which is the basis for the final poem in The Threatened Everything.

PC: I stumbled across the story in my laugher research—I don’t remember where. There was an actual episode of contagious laughter in a school in Tanganyika, which is Tanzania now. Reports vary, but I recall it was a manic, physical reaction to postcolonialism. That breaking apart. I felt that was a thing that tied all of the book together. It wasn’t just laughter as release. It held the possibility for healing, but it was also a symptom, and it was dangerous.

WS: What’s your sense of the possibilities for poetry as a force of social activism? I think of Auden, you know, “poetry makes nothing happen,” but then also of Williams and other people who’ve made arguments for poetry as the news that we need. What’s your feeling about poetry as a mode of expression that has some cultural impact? How do you feel about working with social activism energy through poetry?

PC: Well, Auden’s not wrong, but also, he doesn’t only mean the one thing, because something is being made to happen in that poem. Spending time, “in the valley of [poetry’s] making where executives / would never want to tamper,” is a kind of spiritual practice, which is so embarrassing to say that I’m not even going to take the statement back. When I’m writing and reading, I’m engaging with what is most beautiful, vile, impossible or possible, mundane, lofty, absurd, or lost in the world and in myself. And poets around the world are all doing the same thing. Coming together around that energy can be powerful. Not always. There are endless ways any gathering of people can result in nothing more interesting than a bunch of bruised or blustering egos, but still, I’m really interested in different ways poets make space: from longstanding reading series to house readings to work-in-progress salons. At our best we grow together, circle around each other in times of crisis. The 100,000 Poets for Change global events every fall take on their own identity as they take up a cause. Or, another very micro example, I’ve curated this Poetry Fort at art crawls and other events, which is a tent that can’t seat more than six or so people, two or three of whom are the “featured” poets. There’s an immediate reciprocity; a poet will read a poem and then a member of the quote-unquote audience will say, for example, “I know a song about that” and will sing it. Nobody’s going to achieve literary stardom in that space, but people bring to it and take from it something of real value.

WS: I really like the poem “Super Moon Report” in Quitter. It’s a bit of an homage to the Minneapolis community, where you’ve been central in building community. What’s that work like for you? Does it come naturally, and do you have projects now that you would like to talk about?

PC: I have been thinking back very fondly about when I started hosting an open mic in the late ’90s at the Artists’ Quarter, an amazing jazz club where I worked. I didn’t know any other poets and I needed them. But I was also a single parent and a student and a waitress, so I really needed to multi-task. I rushed in like The Fool in the Tarot deck, fully enthusiastic and totally inexperienced. The organizing work I did then and in later series—sometimes collaboratively—felt necessary. Space needed to be made, and people needed to come together, and it mattered, and so it didn’t occur to me that it was exhausting (a good kind of exhaustion).

Any of the MANY other curators and editors and micropress publishers and culture makers who keep our literary towns so vibrant could tell you the same thing. It is an incredibly fortunate place for a poet to live.

I am not curating more than a pop-up something or other nowadays, but I am thrilled to have recently joined you on the editorial staff at Conduit! It has been on the top of my literary magazine favorites list for decades.

WS: Your work seems to seek community with visual arts and other art forms. How does ekphrasis work for you? Are you actively seeking out visual arts to work with in your writing? What’s the balance or relationship in your life between poetry and other art forms?

PC: Partly, I am a would-be visual artist. I draw and collage mostly. In my office there are two desks: one for writing and one for making objects. When language runs out, I switch seats. Partly, I married a visual artist, Jack Walsh. We collaborate under the name JoyFace, and I can see that my ekphrastic output has increased drastically since we began to influence one another full-time. And partly, there is another great reading series in the Twin Cities called Talking Image Connection, founded by Alison Morse and now run by Luke Pingel, where writers are invited every few months to respond to installations, and I’ve been invited to do that a few times. The creative work of others is profoundly inspiring; responding to it is like picking up a conversation. The poetry manuscript I’m finishing right now is largely ekphrastic.

But I’m not only inspired by visual art. Quitter is full of Chopin and Bowie and Husker Dü and other music.

WS: There’s a lot of doubling and mirroring in both books—imaginative twins, a good one and a bad one, and this concept of an inner wolf/cave problem that your poet-speaker is manifesting. Where do these doppelgangers come from? Are they philosophical or symbological? Do they relate to personal experience?

PC: Even the books have each other as fraternal twins! I mentioned earlier that I was broken in half when writing the poems in The Threatened Everything. And as a culture, too, it feels like we’re divided—not just between antagonistic groups but within ourselves, and many of the poems process that kind of internal split. For instance, in “Cathedral Song, Part One,” the wolf/cave problem reflects on a part of oneself that is denied, or feared, which is probably the part that needs the most attention. In “Cathedral Song, Part Two,” the wolf, who the speaker feared will attack her, leaps out and it turns out that it was just starving, dying of neglect.

WS: Is that part specific for you? What is that part that needs attention but that hides and tries to get your attention?

PC: In this book, I think it was anger. I wasn’t raised with a lot of examples of people expressing anger in ways that were productive or healthy, so I really learned to tamp it down, to deny it existed in myself. I would think, “I am a rational person. I don’t get angry. I look for solutions.” But there’s plenty to be angry about, really, which is, among other things, where the poem “Rage Essay” comes in later.

WS: I don’t know if it’s okay for me to ask, but “Rage Essay” refers to a lost brother, and I’m wondering is that autobiographical? Can we talk about that?

PC: Yeah, it’s . . . yeah, we can talk about that.

WS: What happened to your brother?

PC: I have an older brother who was incarcerated and who was chewed up . . . entirely devoured by that system. I haven’t seen him since I was fourteen. He makes appearances in each of my poetry collections, and I’ve been struggling with how to communicate that loss in a memoir for nearly a decade (The chapbook Misplaced Sinister is part of that bigger project). Our nation’s incarceration addiction is devastating, destructive, dehumanizing, deeply racist. That’s about all I want to say about it.

“Rage Essay” is a pretty traditional sonnet, by the way; I hoped the strict constraint of the form would make the content feel caged.

WS: I hear the poem saying that you don’t want to lose contact with your anger. One of the things that’s trying about this political era is how it seems to be fueled by rage. The last election and some other aspects of our public discourse seem like examples of what can happen when rage takes control. Is there any argument that maybe suppression of rage could actually be a good thing?

PC: Losing contact with the anger wasn’t a choice really, since it existed. I was just choking it down, and so it couldn’t resolve or transform or get put to any good use such as fueling activism. It would come out in weird other ways that were also unproductive and unexamined. And, yes, in that way I was just another broken part of our system.

I don’t think there is any good argument for suppression, but for examining whatever feeling is coming up, without reacting or giving into it. Rage can be self-righteous and deeply ignorant. Sometimes it can provide cover—just a lot of noise so that you don’t have to think or feel anything about complicated solutions which might involve looking at the terrified or ugly part of yourself. That kind of rage can be a drug, really.